Suicide

Why Are We Writing More About a Suicide Than Ferguson Riots?

Are psychologists covering one suicide more than protests over a teen's death?

Posted August 16, 2014

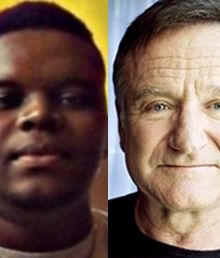

On August 9, a police officer shot and killed unarmed Michael Brown in St. Louis suburb Fergusfon, Missouri. As night fell, citizens gathered with arms raised, symbolically gesturing for police not to shoot. Since then, people have held rallies, tactical officers have arrived in riot gear, reporters covering the protests have gotten detained, police have fired tear gas, and outright rioting has sometimes ensued. On August 15, we finally learned the name of the officer responsible: Darren Wilson.

Here's what some of this website's contributors have had to say about the shooting of Michael Brown and the riots in Ferguson, as of this writing:

- Ferguson Protests, Riots, Power Abuse, and Not-so-Quiet Rage

- The Police and the Military

- When Co-Workers Attack: Lessons Learned from Ferguson

On August 11, actor and comedian Robin Williams was found dead, having ended his own life at age 63 after a lifetime of grappling with depression and substance abuse. People around the world have shown an outpouring of grief for this man who made them laugh and have shared what he meant to them. Suicide prevention has received much attention. On August 14, the actor's wife revealed he was suffering from Parkinson's, a condition that can directly cause depression.

Here are the most recent few examples of what this site's writers have had to say about Williams and related issues, notably suicide and depression:

- The Price of Genius: Robin Williams

- Robin Williams: Genius and Depression from the Same Well?

- Robin Williams' Suicide Was No Surprise

- The Loss of Robin Williams and Holistic Care for Depression

- Tough Truths You Should Know about Addiction, Depression

- "Genie, You're Free"

- Robin Williams Teaches Us about Mental Illness

- Hero, Teacher, Hero, Villain from Mork to the Angriest Man

I'd previously listed the first two dozen such articles on Robin Williams, so I'll not list them again. These few already outweigh our coverage on Ferguson. I'm sure I must have missed a few along the way, but you get the general idea.

So why are we writing that more about one 63-year-old man's suicide than about a teenager's death and the ensuing crisis? Robin's fame obviously figures in, but what else is at work here? Back when 72-year-old actor David Carradine killed himself via autoerotic asphyxiation, that celebrity death did not garner nearly as much attention even in light of its scandalous nature.

Why?

We knew Robin Williams. While most of us never physically met the man, we knew a lot about of his life through news reports, interviews, his stand-up comedy, and his own frank admissions. We saw his very human performances even when he portrayed the most fantastic of characters. We may not have crossed paths Williams in person, but we knew Mork, Popeye, Garp, Genie, the Bicentennial Man, Mrs. Doubtfire, Patch Adams, Teddy Roosevelt, a penguin, one Jack after another, that guy who hated Smoochy, a lot of teachers, doctors, and dads, and many others whose names we don't recall. We don't have to know all the characters' names. They were all Robin Williams. Until this past week, most of us had never heard of Michael Brown.

Robin Williams made us laugh.

The actor had already touched our lives. He meant something to us personally in ways that a lot of other celebrities did not. His performances had touched us emotionally, and we sympathized with him in his roles as rebels and outsiders. Through one character after another, he played someone who struggled with finding ways to relate to others why staying true to - or discovering - himself.

Robin Williams was not simply famous. He was super-famous. When I pointed out, in a paragraph above, that we'd had much more to say about his death than David Carradine's, I doubt that surprised you.

With a suicide, the person who did the killing is the person who got killed, so to whatever extent we might want to cast blame, we don't have to argue how to divide it between killer and victim, whereas we do engage in such assignment of relative guilt when one human being ends the life of another.

We know what to talk about in the case of Robin Williams: suicide, depression, addiction, Parkinson's. We have extensive bodies of literature in each of those areas and plenty of science to back us up. We have no diagnosis for Michael Brown or Darren Wilson.

We can talk about coping strategies to help people deal with those same things. We can steer people toward suicide hotlines, refer them for treatment for depression or addiction, or look up the medical advancements regarding Parkinson's disease. No pill will stop a riot. There is no 12-step treatment program to fix society when it goes wrong.

Racial issues make us wary. Even though I did not say one word about race in my last post about the Michael Brown case ("Ferguson Protests, Riots, Power Abuse, and Not-So-Quiet Rage") because I was focusing that time on what studies by Milgram and Zimbardo have shown us about how authoritative roles can foster conflict, all the comments were about race. One comment writer said she gets tired of being told, "oh, you're just a white girl, you have no clue," when she does discuss race.

The Ferguson situation is ongoing. History is being made. The life of Robin Williams has reached its unfortunate end. The Williams suicide has happened. The Ferguson protests are ongoing. Judging an event while it is in progress can be a trickier thing. Analysis of our kind may simply be premature. For now, it might be more important for us to listen than to speak.

Psychology tends to focus on individuals. Robin Williams is one person. He affected and was affected by many different people, but the moment of his death involved a single person. Michael Brown's death involved more than one in its moment, and has kept growing ever since. Psychological research, nevertheless, does include examinations of group influence and crowd behavior. It just grows harder for us to study and harder still for us to know what to say about it.

Violence fills the news. There are always terrible things happening to people, so people grow accustomed to it. I'm certainly not saying that's right, nor am I endorsing complacency. The world is filled with horrors that happen to other people.

Why else? What other reasons figure into why we've had so much more to say here about one celebrity suicide than the riots over a young man's tragic death? Robin Williams, ever ready to critique life's ironies and to express indignation over injustices, would have had plenty to say about Michael Brown.