Body Image

Warnings That Images Are Digitally Altered? Don’t Bother

New research finds warnings make no difference for women’s body image.

Posted August 23, 2019 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Researchers have spent decades building a persuasive body of evidence that exposure to images of the ultra-thin beauty ideal for women is bad news for body image.

On top of that, these images can play a key role in the development of eating disorders. When those images are digitally altered to create a level of beauty that is truly unreal (instead of just unusual), their effects on women’s self-esteem can be even more potent.

Activists around the world have proposed warning or disclaimer labels as a way to combat the effects of these images. New research out of Flinders University in Australia offers the most recent evidence that such labels are unlikely to do any good – in fact, providing information about digital alteration can backfire.

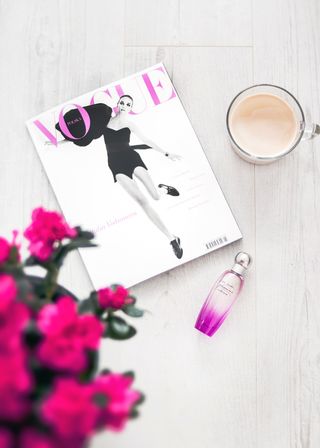

Though recent research has focused on the impact of filtered and Photoshopped social media posts (and even why laughing at those posts is a good idea), fashion magazines remain one of the primary culprits when it comes to selling an increasingly unrealistic version of female beauty.

If you’re concerned about the impact of these images on women’s health, disclaimer labels that say things such as “Warning: This Photo Has Been Digitally Retouched” can sound like a great idea. After all, if you know an image is fake, maybe you won’t feel so compelled to compare yourself to it. And if you don’t compare yourself to the model in an advertisement, maybe your body image won’t take such a hit. These warning labels sound like such a good idea that both Israel and France have enacted laws stipulating that advertising images featuring retouched models must display disclaimer labels. But research has yet to demonstrate that these labels actually help.

The newest study to test the impact of these warning labels was conducted with a sample of over 300 women in Australia ranging in age from 17 to 30. There were two parts to the study. First, the researchers randomly assigned the women to read one of three different short “news articles” created for the study. The first article was titled “We Need to Talk about Photoshop” and the second “We Need to Talk About Comparing.” Both articles included the same content about how Photoshop is used to perfect images of models in magazines, and both articles contained a before-and-after image of a model. The “Photoshop” article included additional information reinforcing the idea that Photoshopped models create an unrealistic standard. The “Comparing” article focused on how it is a bad idea for women to compare themselves with these types of images. For the control condition, women read an article about circulation statistics for magazines; this article did not mention anything about Photoshopping or models.

Next, the women in the study viewed 15 ads from fashion magazines for 40 seconds each. Eleven of the ads contained thin-ideal images of a model; the rest contained only images of products. For half the women in the study, the ads featuring models contained warning labels (“This image has been digitally altered to enhance appearance.”). For the other half, the images did not have warning labels. Women completed measures of body satisfaction multiple times during the study.

Three pieces of bad news emerged from the results. The first is old news: Exposure to fashion images increased women’s body dissatisfaction. This is consistent with numerous other studies and is not surprising.

The second piece of bad news is that the disclaimer labels did nothing to protect women’s body image when they looked at these fashion ads. Instead, the ads increased women’s dissatisfaction with their own bodies regardless of whether they saw warning labels.

Finally, just reading a “news article” about Photoshopped models (or about comparing oneself to Photoshopped models) was enough to increase women’s body dissatisfaction. In other words, just thinking about digital alteration seemed to make women feel less attractive, perhaps because it reminded them of a beauty ideal they cannot meet. On top of that, neither reading an article about digital alternation nor seeing warning labels affected how realistic women thought the fashion images were.

This study adds to a growing body of evidence that disclaimer labels or warnings on digitally altered images do not protect women from their effects. The fact that providing more detailed information about digital alterations of models increased body dissatisfaction is especially alarming.

At this point, there is no compelling evidence that knowing an image is unrealistic will keep you from comparing yourself to it. In fact, digital alteration labels can just emphasize to viewers that the image they are seeing represents an ideal version of beauty – a version they are unlikely to ever meet. The best method for reducing the impact of these types of advertisements may be to simply avoid them whenever we can. So put down that fashion magazine, close your Instagram app, and turn your eyes and your thoughts toward something that builds you up instead of tearing you down.