Loneliness

Can Pets Relieve Loneliness In the Age of Coronavirus?

What does science say about the connection between pets and loneliness?

Posted April 13, 2020 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Recently the Animal Care Center of New York City put out a call for applications to adopt or foster a pet. They were stunned when 2,000 people applied for 200 slots. Katy Hansen, the spokesperson for the organization, attributed this to a combination of time and loneliness.

According to a recent Washington Post poll, nine out of ten Americans are now practicing social-distancing and following stay-at-home orders. It makes sense that people would look to companion animals to help relieve the loneliness of being confined to a house or apartment. I experience the beneficial impact of pets on loneliness myself. When Mary Jean is off on her annual week-long jaunts to the beach with her gal-pals, I feel better having my cat Tilly around, letting me know who’s boss. My newly married daughter, Katie, who works at home, recently got a big cuddly puppy named Moose. Her wife Janna is an ICU nurse who works in a Seattle hospital. Katie says Moose helps her get through long hours when Janna is tending to the needs of the patients suffering from coronavirus.

Like me, most people believe having a pet around the house brightens up the day. A survey by the Human-Animal Bond Research Institute found that 80 percent of pet owners said their pets made them feel less lonely. Researchers at Ohio State University found that avoiding loneliness was the most common reason people gave for living with a companion animal. Further, a lot of studies have found that pets can facilitate social interactions with people, for example, through dog-walking.

Spurred by press reports linking the jump in pet adoptions to coronavirus isolation, I recently took a deep dive into the research studies on the impact of pets on loneliness. I found a surprising mismatch between the near-universal belief that pets make their owners less lonely and the actual research results. These findings raise an important question about the validity of psychological research on the impact of companion animals on our lives.

The Studies

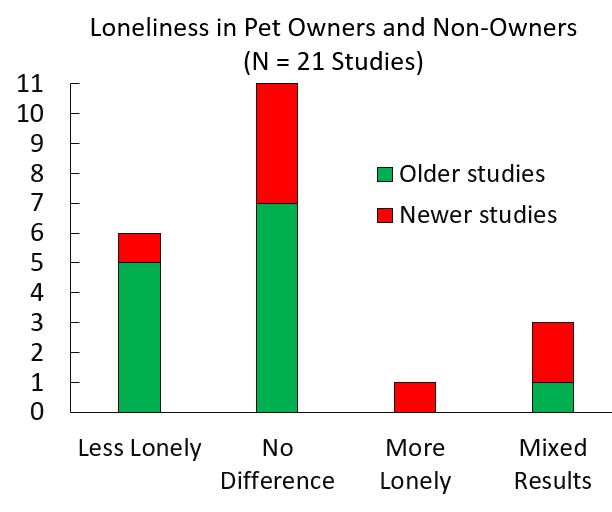

I located 21 studies published between 1986 and 2019 that compared levels of loneliness in pet and non-pet owners. Eleven of the studies focused on older people, and three of them looked at pets and loneliness in children or teens. The UCLA Loneliness Scale is the most widely used measure of loneliness, and various versions were used in 16 of the studies. In several of the studies, however, loneliness was assessed with just one question such as, Have you felt lonely at any time in the past two weeks? Two studies looked at dog owners only, one included only cat owners, and eight of them reported the results for both people living with dogs and/or cats.

Fortunately, in 2015 Andrew Gilbey and Kawtar Tani of Massey University in New Zealand published an exhaustive examination of 13 studies comparing loneliness in pet and non-pet owners published between 1986 and January 2014. Because of their efforts, I only needed to concentrate on the eight studies published in the last five years.

The Overall Results

Let’s look at the big picture before going into some of the finer points of the more recent studies. The big surprise is that only six of the 21 studies found evidence that, as a group, pet owners were less lonely than non-pet owners. Eleven of the studies reported no differences in the loneliness of people with and without companion animals. The good news is that only one research team reported that pet owners were more lonely than non-pet owners. It was a large British study (open access) that found that owning a pet was associated with a 24 percent increase in loneliness in older people (which jumped to a 50 percent increase in women who owned pets).

Several of the studies produced mixed results. For example, Lee Zasloff and Aline Kidd found that while pet ownership did reduce loneliness in women who lived alone, it had no effect on loneliness scores of women living with other people. As described in a Psychology Today blog by Stanley Coren, German researchers reported that women who lived with a dog were less lonely, but that pet-ownership had no impact on the loneliness of men. A 2017 study found that acquiring a dog did not result in lower loneliness scores on the 20-item UCLA Loneliness Scale but did reduce scores on a single item measure of loneliness (“How often in the past week did you feel lonely”?)

Should A Lonely Person Get a Cat?

Maybe. After all, cats can be fun. Nine studies compared loneliness in cat owners and people who did not live with a cat. None of them found that the cat owners were less lonely. In short, as much as I hate to say it, there is not a shred of empirical evidence that getting a cat will make you less lonely.

Older Vs. Newer Studies

The patterns of results of more recent studies on pets and loneliness differ from earlier investigations. Five of the 13 studies published before 2015 reported that pet owners were less lonely than non-owners. In contrast, only one of the eight studies conducted since then obtained convincing evidence that owning a pet was associated with being less lonely, a study of homeless youths.

The discrepancy between older and newer studies may result from differences in the quality of the research. Indeed, Gilbey and Tan wrote in their review of the pre-2015 research, “Overall, we judged none of the included studies as providing convincing evidence that companion animals help to alleviate loneliness.” This sentiment was echoed by Dr. Nancy Gee, Director of the Center for Human-Animal Interaction at Virginia Commonwealth University. In a presentation on pets and loneliness to the recent Summit on Social Isolation and Companion Animals, she told the audience. “Most of the higher quality studies reported mixed results indicating no positive effect of pet ownership.”

An example of an excellent study that produced mixed but largely negative results was recently published in the journal BMC Public Health. Australian researchers conducted the first long-term randomized control trial on the impact of getting a dog on loneliness. The investigators compared the mental well-being of a group of people that adopted a dog with two control groups. At the end of three months, the loneliness scores of the dog group had dropped compared with the other group, and they remained low for the next five months. But, when the researchers factored group differences in education, age and gender into their statistical analyses, the benefits of living with a dog on loneliness and the other mental health measures disappeared.

Why the Mismatch Between Research Results and Our Personal Experience With Pets?

The bottom line is that a substantial majority of the 21 studies did not find that people living with pets are less lonely than people without pets. Further, only one of the eight studies conducted in the last five years found strong evidence that pets reduce loneliness.

The problem is that these results fly in the face of both common sense and the personal experience of most of us who live with companion animals. There are several possible explanations. It could be that we pet owners are deluding ourselves. In their 2010 study published in the journal Anthrozoos, Nikolina Duvall Antonacopoulos and Timothy Pychyl reported that 82 percent of their subjects said their pets had a strong impact on their lives. However, there was no difference in the overall UCLA Loneliness Scale scores of pet owners and non-owners. In addition, in a Psychology Today blog post, Timothy Pychyl suggested that in some people, choosing to spend a lot of time with a pet might be, itself, socially isolating.

And as suggested by researchers from Brunel University who found that pet owners were more likely to be lonely than non-owners, it is possible (indeed probable) that lonely people acquire pets as a form of self-medication, and that they would be even lonelier without their four-legged companion.

But there is another explanation for the mismatch between science and common sense when it comes to the impact of pets on loneliness. Several years ago, I was taking audience questions after a public talk I had given on the impact of pets on the psychological well-being of their owners. Sitting in the back of the room, my friend and colleague Jamie Vaske raised her hand and asked a question. She did not buy my argument that there is surprisingly little good evidence that pets make people happier.

Then she asked a question that stopped me in my tracks, “Hal, do you really think psychologists can measure everything?”

After fumbling around a bit, I finally fessed up and replied, “No. I don’t.”

I’m leaving the door open on the question of whether pets offer a cure for loneliness in the age of coronavirus. It certainly possible that when it comes to our relationship with pets, traditional loneliness scales are measuring the wrong thing.

References

Gilbey, A., & Tani, K. (2015). Companion animals and loneliness: A systematic review of quantitative studies. Anthrozoös, 28(2), 181-197.

Powell, L., Edwards, K. M., McGreevy, P., Bauman, A., Podberscek, A., Neilly, B., Sherrington, C., & Stamatakis, E. (2019). Companion dog acquisition and mental well-being: A community-based three-arm controlled study. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1428.

Antonacopoulos, N. & Pychyl, T. (2010) An examination of the potential role of pet ownership, human social support and pet attachment in the psychological health of individuals living alone." Anthrozoös 23,1: 37-54.

Antonacopoulos, N. M. D. (2017). A longitudinal study of the relation between acquiring a dog and loneliness. Society & Animals, 25(4), 319-340.

Rhoades, H., Winetrobe, H., & Rice, E. (2015). Pet ownership among homeless youth: Associations with mental health, service utilization and housing status. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 46(2), 237-244.