Cognition

The Traumatic Lives of the Famous Sign-Language Using Chimps

"We do not have a right. We can only say we have a need."

Posted March 5, 2023 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

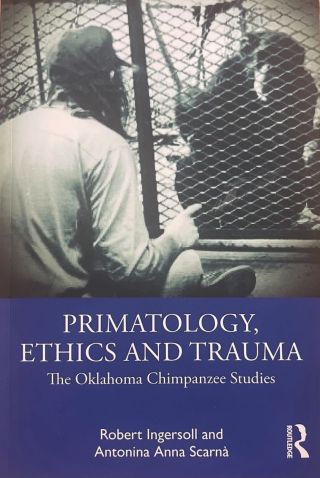

I recently learned of a book by Robert Ingersoll and Antonina Anna Scarnà titled Primatology, Ethics, and Trauma: The Oklahoma Chimpanzee Studies, about how research conducted on chimpanzees came to represent studies reflecting human attitudes toward ownership of animals and different aspects of nature. The authors revisit the methods used to teach language to primates in the quest for psychological science and consider how the impact of this led to traumatic experiences for the animals.1,2

I'm pleased that Bob and Anna could take the time to answer some questions about their new book.

Marc Bekoff: Why did you write Primatology, Ethics, and Trauma?

Anna Scarnà: We hadn’t planned to write a book. I saw Robert in the film Project Nim and was struck by his loyalty and bond with the chimpanzee, Nim Chimpsky. I learned about Nim as a psychology undergraduate many years before, and to see them on screen was remarkable.

In the late '90s, I did a Ph.D. in language acquisition and bilingualism. When we learn a language, we attach linguistic tags to concepts. Over two decades later, I was watching chimpanzees doing the same.

Lockdown happened and in July 2021 I found Robert on Instagram. He had posted a photo of a paintbox, some brown paint, and a bottle of Tabasco that belonged to Nim. I commented that my students at Oxford University were studying language and Nim, and Robert kindly gave a Q&A session from Oklahoma.

I asked whether anybody ever considered these, not as studies of language, but studies of trauma. Robert told me he had waited over 30 years to be asked that, and that I was the person who should write this book with him. If it hadn’t been for that film about Nim, Robert and I would never have spoken.

We wrote our book to clear up inconsistencies in narratives put forward by researchers regarding the roots of language and how primates learn. We are not castigating anyone; we are explaining how the studies were not well planned and why this led to problems in those chimps. We offer different perspectives on why this work should not have occurred and why it should never happen again.

MB: How does your book relate to your backgrounds and general areas of interest?

AS: As I teach theories of psychological disorders and personality, it was obvious to relate Robert’s and the chimpanzees’ experiences to neuroscientific theories. Introducing human language to a nonhuman species creates significant problems around attachment and self-identity, which have rarely been discussed.

The longer-term implications of the chimpanzee work were not considered. Whether they were learning language or not was irrelevant; those captive chimps could only tell us what captive chimps were understanding. Their existence went beyond language and words. These were not studies of language, but studies of humanity.

AS and RI: Since those initial sign language studies, scientific work on trauma progressed fast. Back then, the world did not know much about chimpanzees, let alone about their psychological well-being. We now know about the causes and biology behind stress and about the transgenerational effects of traumatic experiences.3

MB: Who is your intended audience?

AS and RI: Although published by an academic publisher, we wrote knowing our book will be read by a combination of students, professors, therapists, psychologists, primatologists, and others, so we tried to be clear with explanations of language acquisition and theories of trauma. There were lots of question marks over Nim after the film, which we address. Each chimpanzee had their own name, history, and personality, just like humans. It was important to preserve each of those identities.

MB: What are some of your major messages?

AS: It has been 50 years since the first language experiments on chimpanzees. Robert was one of the carers for Washoe, Moja, Tatu, Kelly, Sherry, Booee, Onan, Nim, Denyse, Abigail, and numerous others. We reanalysed those studies considering the neglect and cruelty inflicted in the quest for psychological research.

By definition, these studies failed to address the emotional needs of the animals. What happens if we swap chimp for child? We address the suffering and traumatic experiences endured by the chimpanzees and consider the important bonds between sentient beings.

The chimps taught the researchers who worked directly with them, as well as those who read the books and watched the films over the years. Nim demonstrates the legacy that lives on in every person touched by these stories. There is a bigger context for those findings; they reflect human attitudes toward ownership of animals and other aspects of nature on our planet.

MB: How does your book differ from others concerned with some of the same general topics?

AS and RI: Nim’s history is well documented in Nim Chimpsky: The Chimp Who Would Be Human by Elizabeth Hess. However, other books present the chimpanzee histories with omission, exaggeration, or confusion regarding the true events.

We uncover the historical reality without fabrication and with evidence, in particular around the female chimpanzee, Washoe, and her resultant inability to mother her infant, Sequoyah. That’s her on the front cover in her cage, signing with Robert.

MB: Are you hopeful that as people learn more about these studies they will want changes in the way in which nonhuman primates (and other animals) are treated in research projects?

AS and RI: Like others before us, we are not convinced of any human right to use animals in research. James Mahoney said it best: “I'm thoroughly convinced that we do not have a right. We can only say that we have a need.” We hope there will come a day soon when we are not faced with the dilemma as to what constitutes “need."

Captivity results in traumatised animals. We hope for an end to all invasive research on nonhuman primates. We have tried to be the voice for those chimpanzees, to honor the sacrifices made by their captivity, and to remember them with dignity.

References

1) In conversation with Robert Ingersoll and Anna Scarnà (anna.scarna@conted.ox.ac.uk). Ingersoll was one of the researchers from 1975 to 1983. He is well known for being one of the main carers and best friend of the chimpanzee, Nim Chimpsky, but there were other chimpanzees in the University of Oklahoma's Institute for Primate Studies, including Washoe, Moja, Kelly, Booee, and Onan, who were taught sign language in the quest to discover whether language is learned or innate in humans. Scarnà’s expertise in language acquisition and neuroscience offers a vehicle for critical evaluation of those studies.

2) For more discussion on how researchers can have an impact on the emotional lives of the animals they study see "Bad Science Adversely Affects Animals' Emotions and Reality".

3) The authors note, "We know about the effects of trauma on the human brain through studies on individuals who grew up in Romanian orphanages, and survivors of the Holocaust." Rachel Yehuda et al. Cortisol levels in adult offspring of Holocaust survivors: relation to PTSD symptom severity in the parent and child. ScienceDirect, 2002.