Intelligence

Are Plants Intelligent?

Thinking about "intelligence" and "mindedness" in new ways.

Posted December 16, 2021 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

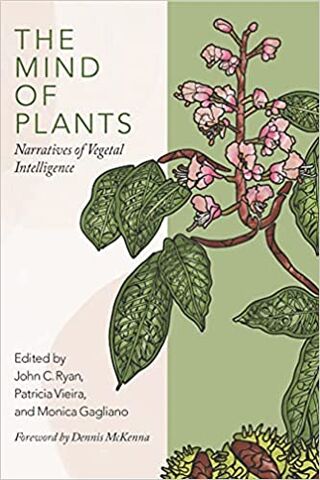

A few months ago I was asked to write an endorsement for a book edited by a diverse group of researchers—John C. Ryan, Patrícia Vieira, and Monica Gagliano—titled The Mind of Plants: Narratives of Vegetal Intelligence.1 I was overwhelmed with the breadth and depth of information contained in the collection of the book's wide-ranging essays. "Animal-centric" views about "minds" need to be broadened to include all living beings on our planet. Science has already shown that merely visiting plants can alter herbivory, including seed production and competition—the Herbivory Uncertainty Principle—so it's important to keep the door open about the inner lives and intelligence of the diverse florae that bless Earth. Bonding with trees can also foster optimism and hope.

All three editors took time to answer a few questions about their forward-looking book.

Why did you edit The Mind of Plants?

The idea that plants have minds has long been a feature of indigenous narratives, literary works, and philosophy. Recent research into plant cognition highlights the capacity of botanical life to discern between options and learn from prior experiences—in other words, to think. We decided to edit The Mind of Plants to create an accessible account, designed for a general readership, on the idea of “the plant mind.” The collection brings together essays, poems, and visual artworks on plants and their interactions with humans. We wanted to highlight diverse approaches to the intelligence of plant life from numerous disciplines and perspectives. The narratives included show how this exciting new research into plant life is entangled with deep personal connections to specific plants, places, and ecosystems.

This book is the result of collaboration between the three editors going back to 2015. We previously co-edited two academic books on plant studies, The Green Thread and The Language of Plants. With The Mind of Plants, we wanted to build on our previous collaborations but go beyond a strictly academic language and format. Our aim from the outset was to bring the personal stories of those who work together with plants in various ways to a general audience interested in the botanical world. On another note, we wanted the structure of our book to pay homage to the herbarium tradition that has preserved botanical knowledge over the ages.

How does your book relate to your backgrounds and general areas of interest?

We represent different disciplinary fields from the natural sciences to the humanities, namely, plant biology, literary and film studies, and creative writing. We understand that only by building bridges between disciplines can we address the complexity of plant forms and their ties to humans. The book’s structure and content—its mix of international contributors—reflect our diverse backgrounds as editors.

Who is your intended audience?

We hope that The Mind of Plants appeals to readers interested in the interactions between plants and humans. Many contributors engage with recent, multidisciplinary research on plants in an accessible style. The book is written for readers seeking answers to the questions and challenges that arise in this time in the history of acute awareness of rapid ecological and social changes. Along with a broad academic audience, our intended readers include horticulturalists, conservationists, activists, medical herbalists, botanical artists and illustrators, musicians and filmmakers, and any curious readers interested in new perspectives on human-plant relations.

What are some of the topics you weave into your book and what are some of your major messages?

As a whole, the contributions emphasize the nuances of the term mind. In one sense, there is burgeoning research into plant cognition suggesting plants are minded. Yet, there are also the myriad ways in which people mind or pay no mind to plants—care for and attend to plants, or disregard and destroy them.

The book’s title also implies a unitary plant mind—a collective intelligence—present in the natural world and out of which individual subjects’ minds arise. The book’s core message is that the mind of plants can be appreciated through stories—“narratives of vegetal intelligence.” Nonetheless, invariably, we found that “the mind of plants” remains an enigma engendering respect and awe for plant life. The idea itself challenges us to think about intelligence and mindedness in new ways—as not limited to organisms with brains and nervous systems.2

How does your book differ from others that are concerned with some of the same general topics?

One of the ways in which this book differs from other publications in the broad area of plant intelligence is its emphasis on the power of story. Plants can be appreciated through scientific analysis and classification but also through the stories told about them. Rather than isolating the plant in time and space, these stories accentuate the dialogues and exchanges between plants and beings other than plants. Stories allow plants to become processes in themselves, constantly undergoing transformation, rather than fixed and isolated objects that traditional plant science attempts to construct. Through its diverse plants, places, people, and passions, the collection invites a rapprochement between systems of knowing plants including scientific, Indigenous, cultural, social, artistic, and poetic.

Facebook image: K-Smile love/Shutterstock

References

In conversation with John C. Ryan, Patrícia Vieira, and Monica Gagliano.

1) John Charles Ryan is Adjunct Associate Professor at Southern Cross University, Australia, and Adjunct Senior Research Fellow at the Nulungu Institute, University of Notre Dame, Australia. His interests include Aboriginal Australian and Southeast Asian literature, ecocriticism, ecopoetics, critical plant studies, and the environmental humanities. He is the co-editor of the forthcoming Postcolonial Literatures of Climate Change (2022, Brill) and coauthor of Introduction to the Environmental Humanities). He has recently served as a Writer-in-Residence at Oak Spring Garden Foundation in Virginia. Patrícia Vieira is Senior Researcher at the Centre for Social Studies (CES) of the University of Coimbra and Professor of Spanish and Portuguese, at Georgetown University. Her fields of expertise are Latin American and Iberian Literatures and Cultures, Portuguese and Brazilian Cinema, Utopian Studies and the Environmental Humanities. Her most recent monograph is States of Grace: Utopia in Brazilian Culture and her most recent co-edited book is Portuguese Literature and the Environment. She has published numerous articles in her fields of expertize, as well as op-eds in The New York Times, the LA Review of Books, and The European, among others. Monica Gagliano is a Research Associate Professor in evolutionary ecology. A former fellow of the Australian Research Council, she is Research Associate Professor (adjunct) at the University of Western Australia and a Member of the Sydney Environment Institute (SEI) at the University of Sydney. She is currently based at Southern Cross University where she directs the BI Lab–Biological Intelligence Lab as part of the Diverse Intelligences Initiative of the Templeton World Charity Foundation. Her work has extended the concept of cognition (including perception, learning processes, memory) in plants. Her latest book is Thus Spoke the Plant.

2) Many plant-mind-related topics are woven into the collection. A reader intrigued by visionary experiences of plants will find chapters by Luis Eduardo Luna (ayahuasca) and Jeremy Narby (cannabis) whereas others interested in Indigenous peoples’ botanical knowledge can turn to contributions by Barry McDonald (fast-moving corkwood), Robin Wall Kimmerer (white pine), and María Luisa Chacarito and Sabina Aguilera (peyote). Those wishing to know more about the science of plant cognition can read essays by Andre Parise and Gabriel de Toledo (bean), Megan Ljubotina and James Cahill (sunflower), and Laura Ruggles (Cornish mallow). For those especially enthused about plants and poetry, there are contributions by Anne Elvey (banksia), John Kinsella (gum trees), Martin Espada (spinach), Rachel Gagen (iboga), and Juan Carlos Galeano (yopo). What’s more, there are chapters on plants and artistic practices, such as those by Renata Buziak (linden), Guto Nóbrega (devil’s ivy), and Harriet Tarlo and Judith Tucker (samphire).

Bekoff, Marc. The Heartbeat of Trees: An Uplifting Spring Read.

_____. Smarty Plants: Research Shows they Think, Feel, and Learn.