Relationships

Compassionate Conservation, Sentience, and Personhood

Conservation efforts should be guided by compassion rather than by killing.

Posted May 23, 2020

"With a guiding principle of ‘first do no harm,' compassionate conservation offers a bold, virtuous, inclusive, and forward-looking framework that provides a meeting place for different perspectives and agendas to discuss and solve issues of human-animal conflict when sharing space." —What is Compassionate Conservation?

A new essay published in Conservation Biology by Dr. Arian Wallach and 23 colleagues from numerous different countries representing a wide range of disciplines argues that there are good reasons to extend personhood to sentient animals in diverse conservation programs.1 This piece, titled "Recognizing animal personhood in compassionate conservation," is available for free online.

Compassionate conservation is based on the ethical position that actions taken to protect biodiversity should be guided by compassion for all sentient beings. Researchers in various disciplines including biology, psychology, sociology, social work, economics, political science, law, and philosophy working closely together have made substantial contributions to this rapidly growing international transdisciplinary field, and there are numerous success stories.2 The four guiding principles of compassionate conservation are: first do no harm, individuals matter, value all wildlife, and peaceful coexistence.

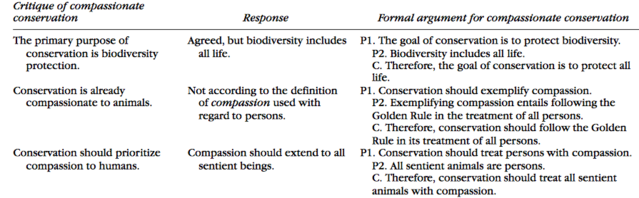

Critics of compassionate conservation argue that there are three core reasons harming animals is acceptable in conservation programs: the primary purpose of conservation is biodiversity protection; conservation is already compassionate to animals; and conservation should prioritize compassion to humans.3 (See "Compassionate Conservation Isn't Seriously or Fatally Flawed.")

The table below displays some formal arguments in support of compassionate conservation that arise from the position that all sentient beings are persons. Each is carefully analyzed in "Recognizing animal personhood in compassionate conservation."

The authors used argument analysis to clarify the values and logic underlying the debate around compassionate conservation. They found that objections to compassionate conservation are expressions of human exceptionalism, the view that humans are of a categorically separate and higher moral status than all other species.

In contrast, compassionate conservationists believe that conservation should expand its moral community by recognizing all sentient beings as persons. Personhood, in an ethical sense, implies the individual is owed respect and should not be treated merely as a means to other ends. On scientific and ethical grounds, there are good reasons to extend personhood to sentient animals, particularly in conservation. The moral exclusion or subordination of members of other species legitimates the ongoing manipulation and exploitation of their living worlds, the very reason conservation was needed in the first place. Embracing compassion can help dismantle human exceptionalism, recognize nonhuman personhood, and navigate a more expansive moral space.

Although the belief that nonhuman animals have some moral standing may be broadly shared among conservationists, compassionate conservation is distinguished by the recognition of nonhuman personhood. Proponents call to include all sentient beings as persons in conservation’s moral community through the cultivation of compassion (Ramp & Bekoff 2015; Wallach et al. 2018). Critics of compassionate conservation generally deny the personhood of all beings but humans by calling for the continuation of programs that harm sentient beings, who are often intelligent, emotional, and social, for the perceived greater good of conservation.

On scientific and ethical grounds, there are good reasons to extend personhood to nonhuman animals (Midgley 1985; Rose 2011; Dayan 2018). The burden of proof should no longer lie with those who seek to expand conservation’s moral community, but rather with those who wish to enforce narrow boundaries (Laham 2009). For compassionate conservationists, sentience is sufficient grounds to recognize personhood. Personhood should not be a status automatically limited to humans. Holding humans separate and aloft from the rest of the living world has legitimated the historic and ongoing exploitation of the more-than-human world, which is arguably the reason conservation was needed in the first place (Plumwood 1993).

Opposition to compassionate conservation is often linked to the legitimate concern that at times conservationists are faced with difficult choices: harm individuals or lose species (Rohwer & Marris 2019). Under such tragic circumstances, it is not clear that any decision can be made with moral impunity (Batavia et al. 2020). Our most quotidian moments harm sentient beings, and choices must be made that inevitably prioritize some over others.

How then is one to act ethically if every act holds the potential to harm fellow persons? There is no easy answer (Batavia et al. 2020). But if one takes seriously the notion that all sentient beings are persons, forming and pursuing conservation objectives founded on mass killing would become inconceivable. The default of domination would be replaced with a default of compassion. [One of the most egregious examples of widespread and deplorable violence lacking any semblance of compassion directed toward millions of sentient animals is occurring right now in New Zealand. (See "Jane Goodall Says Don't Use 1080, Jan Wright Says Use More" for numerous references to their brutal war on wildlife.) These daily and brutal onslaughts on these individuals are business as usual, although in May 2015 New Zealand declared all animals to be sentient beings. As one of my colleagues says, "Go figure."]

That no clean biological or evolutionary boundary separates humans from other animals is widely accepted, yet a stark ethical dualism persists, and abandoning it remains an almost unthinkable proposition. Some suggest that compassionate conservation is too subversive to even be allowed space at the table, going so far as to proclaim that “compassionate conservation is not conservation” (Driscoll & Watson 2019). Such a diktat risks harming the open exchange of ideas on which scholarship depends. If conservation’s sole purpose is to protect native ecological collectives with little regard for other moral claims, then it is fair to say that neither compassionate conservation, the wider academic community, nor prevailing social values are aligned with conservation.

Advocates of compassionate conservation embrace compassion for its ability to bridge between ourselves and Earth’s great diversity of persons. Compassionate conservation offers a way forward, to seize the challenges and opportunities that rise in the dust of our crumbling dualisms. Killing "in the name of coexistence" doesn't make much sense, and scientists agree.

It's essential to recognize that compassionate conservation is not a challenge to conservation per se, but rather a good-faith response to growing societal recognition worldwide that nonhuman animals feel, that they have lives, experiences, and relationships that matter to them, and that should matter to us. [Compassionate conservation isn't "animal liberation dressed up as conservation science." This is an uninformed cheap shot that is seriously flawed.]

We must replace our habits of domination and exploitation with compassion if we are to make the world a better place for nonhuman and human animals alike in an increasingly human-dominated world. The Anthropocene, often called "the age of humanity," is better characterized as "the rage of inhumanity," and countless nonhumans and their homes are brutalized each and every day. Compassionate conservation asks people to "rewild their hearts" and to connect with all of nature.

Compassionate conservation is no longer an oxymoron and has no hidden agenda. It considers all stakeholders, nonhuman and human. It is firmly grounded in solid biology and stresses that conservation biology must be firmly rooted in ethics even if difficult questions move us outside of our professional and personal comfort zones. And, while progress will only be made when all voices are heard, it's not asking too much to expect them to be informed about what they're arguing for or against.

I look forward to future discussions about the importance of compassionate conservation for leading the way in diverse global conservation efforts. Indeed, it already has.

References

Notes:

1) Arian D. Wallach, Chelsea Batavia, Marc Bekoff, Shelley Alexander, Liv Baker, Dror Ben-Ami, Louise Boronyak, Adam P. A. Cardilin, Yohay Carmel, Danielle Celermajer, Simon Coghlan, Yara Dahdal, Jonatan J. Gomez, Gisela Kaplan, Oded Keynan, Anton Khalilieh, Helen Kopnina, William S. Lynn, Yamini Narayanan, Sophie Riley, Francisco J. Santiago-Ávila, Esty Yanco, Miriam A. Zemanova, and Daniel Ramp (Authors' affiliations can be seen in the essay.) Some of this piece is excerpted from this open access essay on which I'm a co-author. It is an excellent example of close teamwork by researchers with diverse interests. In a few places I've used brackets to indicate additions, including the opening quotation and the first two and last three paragraphs.

2) Numerous examples of success stories can be found in the essays below, and many are summarized in Summoning compassion to address the challenges of conservation and on the website for the Centre for Compassionate Conservation at the University of Technology, Sydney.

3) Some criticisms of compassionate conservation have been ad hominem, some rather insulting, and some show the authors clearly miss at least two important aspects of compassionate conservation. These are: 1) compassionate conservation, like traditional conservation, is all about protecting biodiversity and (2) all stakeholders, nonhuman and human, are important in conservation decisions. All criticisms have been taken serious and were part of the reason we wrote "Recognizing animal personhood in compassionate conservation."

Batavia, C., Nelson, M. P., and Wallach, A. D. The moral residue of conservation. Conservation Biology. 2020.

Bekoff, Marc. (editor) Ignoring Nature No More: The Case for Compassionate Conservation. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2013.

_____. Compassionate Conservation Isn't Seriously or Fatally Flawed.

_____. Killing "In the Name of Coexistence" Doesn't Make Much Sense.

_____. Killing Barred Owls to Save Spotted Owls? Problems From Hell.

_____. Thousands of Cormorants to be Killed: There Will be Blood.

_____. An Ape Ethic and the Question of Personhood. (An interview with Gregory Tague about ways in which apes are moral individuals).

_____. Compassionate Conservation Isn't Veiled Animal Liberation. (This growing field isn't "animal liberation dressed up as conservation science.")

_____. Compassionate Conservation Matures and Comes of Age. (Among the major goals of compassionate conservation is killing isn't an option.)

_____. Compassionate Conservation: More than "Welfarism Gone Wild."

_____. Compassionate Conservation Finally Comes of Age: Killing in the name of conservation doesn't work.

_____. Animal Emotions, Animal Sentience, and Why They Matter.

_____. Accusations of "Invasive Species Denialism" Are Flawed.

_____. Rather Than Kill Animals "Softly," Don't Kill Them at All.

_____. A Journey to Ecocentrism: Earth Jurisprudence and Rewilding.

_____. Rewilding Our Hearts: Building Pathways of Compassion and Coexistence. New World Library, Novato, California, 2014.

Dayan, C. Personhood. Pages 267–279 in Gruen L, editor. Critical terms for animal studies. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Illinois, 2018.

Driscoll, D. A, and Watson, M. J. Science denialism and compassionate conservation: response to Wallach et al. 2018. Conservation Biology, 33:777–78, 2019.

Midgley, M. Persons and non-persons. Pages 52–62 in Singer P editor. In defense of animals. Blackwell, New York, 1985.

Mountain Journal. What Does It Mean To Be An Animal Person?

Plumwood V. Feminism and the mastery of nature. Routledge, New York, 1993.

Ramp, Daniel and Marc Bekoff. Compassion as a Practical and Evolved Ethic for Conservation. BioScience, 65, 323-327, 2015.

Rower Y. and Marris, E. Clarifying compassionate conservation with hypotheticals: response to Wallach et al. Conservation Biology 33:781–783, 2019.

Rose D. B. Wild dog dreaming: love and extinction. University of Virginia Press, Charlottesville, Virginia. 2011.

Wallach, Arian, Chelsea Batavia, Marc Bekoff, et al. Recognizing animal personhood in compassionate conservation. Conservation Biology, 2020.

_____, Marc Bekoff, Michael Paul Nelson, and Chelsea Batavia. Promoting predators and compassionate conservation. Conservation Biology 29(5), 1481-1484, 2015.

_____, Marc Bekoff, Chelsea Batavia, Michael P. Nelson, and Daniel Ramp. Summoning compassion to address the challenges of conservation. Conservation Biology 32 (6), 2018.