Relationships

Dogs Aren't Hard-Wired "Love Muffins"

Casual observations and science tell us that dogs have active brains and hearts.

Posted November 30, 2019 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Saying that dogs are unconditional lovers and our best friends sell, but they're unsubstantiated myths

Somehow I missed a recent essay called "Dogs Can’t Help Falling in Love" with the subtitle, "One researcher argues that a dog’s ability to bond has more to do with forming emotional attachments than being smart about what humans want." I was alerted to this piece by a number of emails and was taken by the fact that not a single person who wrote to me agreed with the suggestions that dogs can't help falling in love and are not all that smart. I agree. After I read the piece, I found a number of questionable claims. For example, in the essay, we read, "Dogs have 'an abnormal willingness to form strong emotional bonds with almost anything that crosses their path... And they maintain this throughout life. Above and beyond that, they have a willingness and an interest to interact with strangers.'”

Nonetheless, readily available information—data and stories—clearly shows that dogs are very smart and clever and aren't unconditional, hard-wired lovers. In fact, they're very choosy about the humans with whom they bond and possibly fall in love, and surely, they aren't our best friends. (See "'My Own Dog Is an Idiot, but She’s a Lovable Idiot,'" "Are Dogs Really Our Best Friends?" "Are Dogs Really Our Best Friends or Family?" and "Chimps and Dogs Are Very Smart.")

These misconceptions set up false expectations of who dogs really are and don't serve them well. So, if a dog doesn't connect with you or seem to love you, there isn't necessarily something wrong with you. We need to be sure that we're not setting dogs up for failure, failure to be who we think they should be, but not who they truly are.

I also was reminded of an interview in Scientific American with Dr. Brian Hare, co-author of The Genius of Dogs with Vanessa Wood and founder of the Duke Canine Cognition Center. Hare was asked, “What is the biggest misconception people have about the dog mind?” He answered: “That there are ‘smart’ dogs and ‘dumb’ dogs...There’s still this throwback to a unidimensional version of intelligence, as though there is only one type of intelligence that you either have more or less of.”

Dogs display multiple intelligences of the "dog kind" with lots of variation

I agree, as do many others, that dogs display multiple intelligences of the "dog kind" and that it doesn't really matter if they're as smart as other nonhuman or human animals because cross-species comparisons in intelligence are fraught with error. I always say that animals need to do what's needed for them to be "card-carrying" members of their species, and we must remember that numerous nonhumans outperform us in many different ways. So, comparing different species doesn't mean very much.

I really like how Hare and Woods write about this topic: "The cognitive approach celebrates many different types of intelligence and liberates us from the idea that intelligence is a linear scale with sea sponges at the bottom and humans at the top. Asking if a dolphin is smarter than a crow is like asking if a hammer is better than a saw. Which is a better tool depends on the task at hand or, in case of animals, which challenges they must regularly confront to survive and reproduce."

"Dogs Can’t Help Falling in Love" motivated me to think more about the cognitive and emotional lives of dogs. Research and citizen science tell us that dogs have very active minds and hearts. And surely, assigning human-like emotions to dogs and other nonhuman animals (animals) isn't a "load of crap," ridiculous, or dangerous, and surely, it's not only "damn leftists" who do so, as suggested in a recent comment to one of my previous posts. (See "Animal Rights Advocates Aren't Lefties Who Don't Like Humans.")

Tales about tails and Darwin's Principle of Antithesis

A dog's tail is a fascinating piece of work, and they often use it as an expression of love and other emotions. Numerous people want to know how dogs use their tails, and once again, there are some general claims that aren't supported by any systematic research.

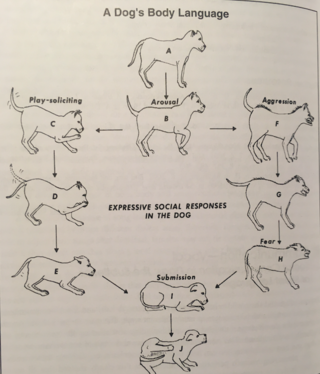

It's well known that dogs use their tails alone or in combination with other modes of expression in a variety of ways during social interactions with dogs and other animals, including humans. Their tails also move in a variety of ways when they're alone.

However, there still is a lot we don't know, and there are myths about how they're used. For example, in Inside Your Dog's Mind: What They Really Think, in which there is some very interesting material, there also are some claims that are misleading given what we know about these amazing beings.

Focusing on dogs' tails, a statement by veterinarian Laurie Coger caught my eye. She states, "When a dog sticks his tail straight in the air, he's trying to make himself look bigger, so he doesn't have to fight." Stated with such unwavering authority, one might be tempted to think this is true. But neither I, nor researchers I've asked, can find any research that has actually focused on Coger's interesting idea. I asked pioneering dog expert, Dr. Michael W. Fox, about it, and he sent me the following answer:

"My interpretation of the upright tail in various canids is related to context/situation. My dog Kota's tail usually goes up when she goes outside, an indicator of arousal/vigilance. An upright tail is often associated with excitement in anticipation of play.

"In other contexts, as when two dogs meet and know each other, tails are up and wagging like flags. When they do not know each other, the more confident dog has the tail is up and is wagging it stiffly... Dogs with docked tails may have signaling deficits when interacting with other dogs. I have never interpreted upright or arched-over-the-back tail postures as the dogs' way to look bigger so they do not have to fight. This is too simplistic. Rather, as Charles Darwin pointed out in his principle of antithesis, many of the body posture displays of canids and other animals can give the illusion of greater or lesser size to either intimidate, assuage, solicit, or test how the other animal is going to respond.

'In sum, dogs' tails, like their ears, serve as appendages of communication and interrogation. For more details, see my book Behaviour of Wolves, Dogs and Related Canids. In my observations of a wolf interacting with dogs, the wolf generally interpreted dogs approaching with an upright tail as being challenging, which, in most instances, was not the dogs' intent! With dogs such as the Old English sheepdog, whose tail, ear, and facial expressions were not evident, this wolf was very guarded. I hope this helps clarify things and underscores that the tail does not wag the dog, and none should have them cropped, or their ears!"1

I agree, and it's exciting to look forward to further research into how and why dogs use their tails the way they do, either alone or as part of composite signals incorporating other parts of their bodies and possibly different vocalizations and odors. Composite signals contain more information than signals in a single sensory modality. Similar to other animals, including humans, dogs often express a cocktail of stimuli simultaneously and sequentially.

Some take-home messages

Unfortunately, alt-facts about who dogs are and why they do what they do and what they know, think, and feel are far too often presented as facts, and some of these circulate especially through popular media as memes that are supposedly well-accepted within the scientific community. However, it's clear that oversimplified explanations of what makes dogs tick don't work.

It's essential to become fluent in dog, or dog literate. When we think we know everything there is to know about dogs, we're clearly wrong: Sweeping, species-wide generalizations about why dogs do something, think something, or feel something have little merit because there's no universal dog. Suffice it to say, there are few generalizations that apply to all, or even most, dogs, so speaking as if there's some sort of prototype dog is misleading.

Most people who write about dogs are usually referring to homed dogs; in fact, mainly homed Western dogs, who represent a small fraction of the world's dogs. The more I know about dogs, the more I say I don't know when asked many questions about why they're doing what they're doing.

Concerning dogs' intelligence, it can safely be said that dogs aren't dumb nor are they dumb-downed wolves. They're also not hard-wired "love muffins." Anyone who's rescued an abused dog knows how choosy they can be and how difficult it can be for them to come to trust humans. Two questions of interest are: (i) Why do some dogs seem to bond easily and closely with many humans? and (ii) Why are other dogs more choosy and defy being called "unconditional lovers?" Saying that dogs are unconditional lovers and our best friends sell, but they're unsubstantiated myths

What with a good deal of past and ongoing research, along with the contributions of citizen scientists and trainers, some of whom know a lot about dog behavior, discussions about the cognitive and emotional lives of dogs will likely be exciting and filled with differing views about dogs' minds and hearts and how much consistency and variability there really are. It's also essential to watch free-running dogs and not limit ourselves to data collected in highly controlled laboratory situations, often on a handful of dogs.

All in all, all sorts of input are necessary to learn more about dogs' minds and hearts. Concerning the role of trainers, Jessica Hekman writes, "The perspective of dog trainers, with their deep experience in real-world canine abilities, provides a rich source of theories for academics to test. Collaboration between dog trainers and research scientists could lead to a partnership that deepens our understanding of canine cognition." Along these lines, she notes, "Trainers working with dogs every day have documented extraordinary talents and skills. Will science ever catch up?" Let's hope it does.

Check back for further discussions of the rich, deep, and varying cognitive and emotional lives of dogs. While we know quite a lot, there's still lots to learn, and that's why studies of dogs' cognitive and emotional capacities are such exciting areas of research that are attracting a lot of attention.

References

Note 1: Quoting Charles Darwin on his Principle of Antithesis:

"Certain complex actions are of direct or indirect service under certain states of the mind, in order to relieve or gratify certain sensations, desires, etc.; and whenever the same state of mind is induced, however feebly, there is a tendency through the force of habit and association for the same movements to be performed, though they may not then be of the least use."

Barash, David. Chimps and Dogs Are Very Smart.

_____. How Ethologists Learned to Respect Animal Minds.

Bekoff, Marc. When Dogs Play, They Follow the Golden Rules of Fairness.

_____. When We Go to the Dogs, There’s Much More Than Meets the Eye.

_____. The Dog's Tail Tale: Do They Know What Others are Feeling?

_____. Do Dogs Recognize "Dog" and What They're Feeling From Afar?

_____. Canine Confidential: Why Dogs Do What They Do. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2018.

_____. The Messes Dogs Make: Science Shows "The Dog" Doesn't Exist.

_____. "'Why Do People Make Up Myths and Other Stuff About Dogs?'"

_____. Dogs: The More I Know, the More I Say, "I Don't Know".

_____. Dog Training Offers Valuable Lessons in Humane Education.

_____ and Jessica Pierce. Unleashing Your Dog: A Field Guide to Giving Your Canine Companion the Best Life Possible. New World Library, Novato, California, 2019.

Many of my essays on all things dog can be found here.

Hekman, Jessica. Canine exceptionalism: Trainers working with dogs every day have documented extraordinary talents and skills. Will science ever catch up? Aeon.

Schenkel, Rudolph. Expressions Studies on Wolves. Behaviour, 1947. (a classic and very important essay)