In my last post, I wrote that I want to share some client narratives that have been fearsome, but also have had elements of strength, sometimes hidden under many layers of failure, trauma, loss. The stories remind me that positive change can occur.

Here’s beautiful Joe, a 35-year-old, bisexual man, as he sits on the couch in my office. His muscular chest in a tight t-shirt, his thick brown ringlets hiding his face, until he finally looks up and meets my eyes with his dark-lashed blue ones. He looks like an anxious boy, with a combination of embarrassment, failure, and guilt on his face. Our therapeutic attachment has created a maternal worry-meter inside me; it starts to clang.

“A couple of days ago, I bought some dope.”

(Among other things, Joe has taught me more than a few terms for heroin. The first time he had used the term “dope,” I thought he meant marijuana and was coolly unsurprised, until he said “H” a few sentences later and then confirmed my fearful suspicion by talking about shooting up.) This time, I do not allow my face to react to the news of his purchase, though I can feel my chest tighten in defense against the relapse that surely happened.

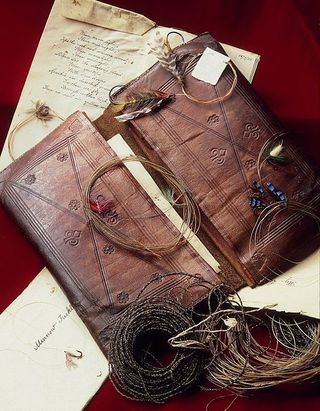

Joe goes on: “I pulled off by the side of the Connecticut.” (That's the river where Joe fly-fishes when he’s not high.) “I was desperate to get high, and had what I knew was good dope.”

He’s watching me, and I keep my face still. I’ve learned that he’ll stop and adjust his story if I react in any way whatsoever. I want him to be able to tell me what he’s done; Joe has enough shame about substance abuse to last a hundred lifetimes.

He resumes his story, “I get out my rig, heat the junk. Just as I am tightening up, I look out the windshield at the truck that had just passed, and I see it was my dad.”

He stops, and his voice fills with tears. His hair covers his face again, head and eyes focused on the tear in the knee of his ultra-cool Levi’s.

He looks up, “It’s dumb, I know, but for a minute I thought he was out looking for me, and that he’d turn around and come back to my car and—”

“And what, Joe?” I ask quietly after a moment has passed. “What did you hope he might do?”

“Stop me,” he whispers.

We sit in silence for a long minute. He looks up again, meets my eye.

“But of course he didn’t. He probably didn’t even see me.”

I raise my eyebrows, hopeful he'll say more about that possibility, be able to acknowledge the love his father has for him.

As he opens his mouth to continue, I realize that I am really sad, and again afraid that Joe's self-harm with drugs may actually kill him. Perhaps my face changes; he pauses.

“What did you do?” I say at last.

He laughs without joy, without humor, “I pulled out on the road a few cars behind him, and I sank that sucker in my arm.”

“You shot up when you were driving?” I say in disbelief. His bipolar disorder is under pretty good control these days, and this impulsivity shocks me.

“Yeah,” he answers with a shrug.

Another pause. Joe pulls at the loose, white threads over his bare knee.

“I know it’s dumb,” he says quietly. “I know I could die.”

“Oh, Joe,” I breathe.

He breathes.

I go on, “I don’t want you to die, Joe. I care about you.”

He nods, head still down.

“Can you look at me?”

He finally lifts his head and meets my eyes. The long moment feels like an act of communion.

“I care about you,” I repeat. “And I worry that you might kill someone else too, and that would destroy you.”

I hold the look, and then he breaks it. Shame floods his face, like a wave on the seashore, then dissolves, vanishes.

“I’m sorry,” he says under his breath like a schoolboy, afraid of rejection.

“I’m not blaming you, Joe. I’m telling you that you matter. People care about you.”

At that, he looks up again, a doubtful twist to his mouth.

I go on, “I care about you. Your father cares, and if he had seen you, he would have turned around and stopped you. Your mother cares, your sisters care, your friends and bandmates care.”

Joe has tears in his eyes; he brushes them away.

“You’re the one who sometimes doesn’t care about you.” He looks startled this time, and I realize that perhaps he has never seen his situation that way. “We all care for you in the ways that we can.”

I think about his father, throwing work his way; his mother paying his cell phone bill; his siblings checking in every few days, taking him to lunch, buying him guitar strings and veggie burgers. His friends offering a couch, a home for his cat. His bandmates showing up and giving him a chance to sing.

Perhaps he thinks about some of those things too. He’s silent for a long moment.

“I don’t really want to kill myself,” He says at last.

“I know.”

“What can I do?” he asks. “How can I save myself?”

An ancient cry, his words pierce my boundary with him, and I feel the tears fill my eyes. A few fall on my cheeks.

I say what comes to mind, a bit of ancient wisdom: “Fish, Joe. You need to get into the river, cast the fly, and fish.”

He hears the literal idea, and smiles, “Yeah, that helps a lot. I could carry my gear in my car.”

“What if you carry the fishing gear, and don’t carry the heroin rig?”

He flushes a bit. It’s a hard negotiation.

“Can you do it—care for yourself?”

At last he says, “I can try.”

I smile at him, “That’s exactly right. That’s what fishing is, right? Trying.”

He meets my eyes, “Yes. Fishing is an act of trying.”

Our eyes flood with tears. He stands to go. He’s much bigger than I, and he bends to embrace me. Simultaneously, he whispers “Thank you,” and I whisper “You can do this.”

“See you next week,” he says as he turns toward the door.