Catastrophizing

The Isolation of Catastrophic Thinking

How the rites of spring and spirit can help keep disaster at bay.

Posted April 16, 2019

I’ve been self-employed for three years. Every year I have worried about my taxes.

This year, with the new tax code, a legacy from my mother’s estate, and my own ostrich tendencies, I am surprised to owe a significant amount of money, enough to render me ineligible for the excellent state health insurance plan that has kept me safely supplied with the supplies I need to manage Type 1 diabetes. With recent stories in the national news about people dying because they can’t afford insulin, I am suddenly terrified: what if my new, allegedly affordable insurance, is too expensive with its deductible, premiums and co-pays? Will I have to give up my insulin pump? Will I have to get a second job to keep it? What would that job be? When could I do it? My brain ramps up, 0 to 60 in 2 seconds.

After a few minutes in overdrive, I feel so tired! I tell myself: Don’t be ridiculous, Elizabeth! Of course you can pay for what you need! And if that isn’t strong enough to calm me down, I move to: Turn it over to the universe, Elizabeth! It will work out! And if the heart is still pounding and I continue to forget to breathe, I go to my great fallback position, which I know I am incredibly lucky to have: If you need to, Elizabeth, you can ask your family for help. Sometimes I then move to worrying about how I would ever pay them back but that’s far enough from imminent catastrophe that I’m usually able to regain rationality.

I make the switch in insurance with the help of Phil, who used to work at the homeless shelter in town, and now helps people navigate the complexities of the Affordable Care Act. He points out that an upcoming surgery will result in my paying the whole $2,000 deductible all at once. I’m perversely relieved, because then I won’t have to worry about paying hundreds of dollars for every bottle of insulin. Insulin is, to me after 46 years of diabetes, as integrated into my life as toilet paper or toothpaste. I can’t bear to think about being worried about whether I can afford it. And now Phil’s pragmatic approach makes it possible for me not to do so. Of course the $2,000 deductible is still an issue! But having it earmarked and therefore not free-floating, a fixed rather than generalized anxiety, keeps catastrophe at bay.

Phil’s my neighbor, probably quite a bit like me: single, far from wealthy, committed to helping people who need help. He paused after completing a sentence when he was helping me: “I’m working with pretty much the same population that I worked with at the homeless shelter,” he says. I think of the clients we shared: Stan, who has bipolar disorder and a prolonged addiction to both heroin and cocaine. Gilda, who has painfully fierce delusions that she is being stalked. Both are now in stable housing (a trailer, and a one-bedroom apartment), on some form of Social Security, and somewhat less miserable than they were when Phil and I started working with them. I’m aware that in many ways, I am not similar to the population that moves through our local shelter; but as he speaks, and then pauses, I realize that we both see that I could be, and if I could be, so could Phil. The degrees of separation at the lower end of the economic pyramid are pretty small these days. If we lose our jobs….

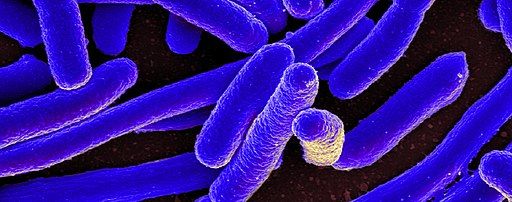

The week becomes more stressful, and my thinking more catastrophic, when our municipal alert system delivers a robocall that the town water has tested positive for E. coli. We have to boil, or use bottled water till further notice. No brushing teeth or washing dishes with tap water. Throw out old ice cubes, reconstituted baby formula, and other comestibles made with tap water. I suddenly realize how we rely on having clean water. The community is befuddled: can we bathe in the water? Can we use a dishwasher? Can our pets drink the water? Where did the E coli come from, anyway? How long will it take to get back to our first-world normal of being able to take our water for granted?

The next day, the town sends another alert announcing that the original test for E. coli was a false-positive. I can stop panicking about dysentery, cholera, typhoid, or any of the other life-threatening diseases carried by contaminated water. I remind myself that we have a Water Department that responds quickly and efficiently to the regular testing that keeps our water safe. But I still find myself thinking, if we lose our clean water….

Later in the week, there is a photograph of a girl from Guatemala in the newspaper: there is discussion that thousands of migrant children like her might be returned to their native countries without their parents. Another option, sanctuary cities, is bandied about the country; I think about sanctuary—for me, a holy place offering rest and safety. And then I am full of fear and rage that it might come to that. I see an editorial cartoon of the President looking at children held in cages.

I think back 40 years to our church offering sanctuary to a family with young children seeking asylum from war-torn Nicaragua; further back to the Japanese interment camps in California, where children were displaced from their homes because of institutionalized racism, and then to the child Anne Frank, first forced from her home into hiding because she was Jewish, then discovered, seized, and murdered in a Nazi concentration camp. I find myself thinking, if we continue to fail to protect the world’s children from political disaster….

At the end of the work week, I’m exhausted by my own catastrophic thinking, and aware of how many of my therapy clients have expressed similar patterns of thought. Anxiety is soaring in our community, country and world. So many of us feel isolated, alone, afraid. My fears of economic insecurity, threats to health, loss of natural resources, and political unrest are minute compared with my contemporaries in other places. I do not lose sight of my privileged position as an independent woman in a wealthy country. But I am deeply rattled by the pattern of catastrophic connections my mind has been forming: the what-ifs are harder to fend off these days.

On Saturday, I go to an ecumenical Freedom Seder some friends host every year. Their Seder focuses on slavery and ways to achieve liberation in our contemporary world. As we celebrate the beauty of spring and of human love, we read in their wine- and tear-stained Haggadah about the slavery of racism, sexism, homophobia. We face the depth and breadth of sin and hatred as we recite the numbers of people killed at each concentration camp. And then we are reminded of the wisdom of children, and of the meaning in the answers to the question, “Why is this night different from all other nights?” We take time to savor the bitter herbs in combination with the sweet apples and nuts. We contemplate our own lives, and also our larger, shared human life. We eat delicious food, laugh a great deal, welcome Elijah and remember loved ones who are not with us. I go home and have the first deep and peaceful sleep I’ve had all week. Slavery has given way to human connection, despair mitigated by a glimpse of hope.

The next morning is Palm Sunday, typically a joyful time at church. But of course the story of Jesus, like the story of the Exodus we celebrated at the Seder, is a story of life, not all joy. We are reminded of the part of the Lenten story that comes between Palm Sunday and Easter. There’s betrayal, denial, violent humiliation, pain and suffering—there’s a wretched and heavy load of catastrophe in the story, which reflects human life, just as the story of the Jews’ exodus from captivity reflects human life. I leave church after the service with a renewed commitment to bear witness to slavery—those migrant children—and to the hope that as individuals and as a people, we can turn our current catastrophes into spiritual connection and possibly even growth.