Anxiety

Anxiety and Loneliness After a Life of Independence

How reviewing childhood—and a really nice cat—can help.

Posted March 14, 2019

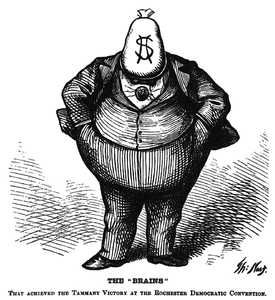

The first time I make a home visit to Lee, I almost don’t get past the front door. It is covered with political cartoons, and I stand there reading them and laughing for several minutes before I remember I’m here as a therapist for a reserved and anxious person. Lee is going to have that effect on me, I can tell from first impressions: She wears her mind on her sleeve so that no one will have a chance to break her heart.

Lee has lived in a wheelchair for 35 years. In adolescence, her athleticism led to a scholarship in college before her knees gave out. Fifteen years later, she was diagnosed with osteomyelitis, a rare infection of bone marrow after traumatic injury. One leg was amputated above the knee, changing Lee’s life in multiple ways. She withdrew from a Ph.D. program and began to build a life devoted to advocacy for people with disabilities. She won a national award as an advocate and continues to work for equitable opportunity, access, and recognition for people with differences.

Her humor helps with chronic pain and with frustration: “I’m now working to get transportation that I fought for and got years ago, and then they took away.” She looks at me and laughs. “How many times are we going to have to fight for this? We will continue to do it, time after time. We’re not going away.”

Lee lives with her service dog, a calm and friendly retriever named Umbra, “the shadow in an eclipse,” she explains. “I like it when she eclipses me.” She also has a very small tortoiseshell cat (only 7 pounds on a good day), Lulu, who is sleek, with a gold line down the middle of her forehead and one blonde front paw. The two animals are vivid presences in the home, and they live in peace. Lee is careful to pay attention to each, noting that Umbra “gets a little jealous if Lulu gets all the love, and Lulu disappears if it’s all about Umbra.”

This week, I sit on the couch and Lee sits facing me in her wheelchair. Her right pant leg is neatly folded over; her left foot is on the solitary foot rest. “I want to talk about my feelings about my parents,” she says at last.

I nod, waiting. I know that her parents, although dead, are in some heavy way still present in her life. Her beloved father died young; her mother had a second relationship with a man whom Lee liked.

Lee looks at me, before turning her face away and saying, “My mother wanted a girlie-girl.” I nod again, aware of some mothers’ desire for a doll, or an alter-ego, or a twin. “She wanted a girlie-girl, but she got me.” Lee looks at me again, meets my eyes straight on.

“And you’re not a girlie-girl.” I state the obvious, and she laughs.

“Nope. Not by a long shot. I always liked sports, wasn’t interested in boys—or girls, for that matter. I’m pretty asexual. I was interested—am still interested—in books, literature, history, science. I don’t have a lot of use for people.” She looks over at Umbra, who stands and comes to her. “The animals help me a lot.”

“They’re wonderful,” I affirm, looking across the room where Lulu lies in a snug cat-ball, her eyes flickering.

Lee smiles as she too looks at the watchful cat. “I don’t know what I’d do without them.” She pauses a moment and then says, “I always wanted to be alone, reading a book or listening to music. But now—” she pauses again and draws a breath for courage. “But now, that attitude is coming back to haunt me.” Another breath, and then on the exhalation, quickly, “I’m lonely.”

The word sits there for a moment as I wait to see if anything more will come. Nothing does.

“You’d like to have more people in your life now?” I ask gently.

“At least one friend, someone I could call on when I—when I feel anxious. I have cataract surgery coming up, and I’m terrified, and I don’t have anyone close to go with me. A woman I know will help, but she’s in a wheelchair too, and it is hard for her to get around and hard to organize transportation for us both together.”

“So, one of the things you might like to focus on in therapy would be dealing with loneliness by making some friends?”

She looks relieved that I have understood. Or perhaps that I don’t think that this is peculiar—or impossible. She says, “Yes,” in a small voice.

I’ve been watching Lee’s face, listening to the emotions in her voice. I’m startled when I suddenly see Lulu cross in front of the wheelchair and come over to the couch. Lulu gazes up at me, contemplative. Then she jumps up on the couch.

“She never does that,” Lee says.

“Is it okay?” I ask.

“Oh yes.”

We keep talking, but Lee also keeps watching Lulu, who approaches me.

We resume our conversation about loneliness, and Lee returns to family dynamics. “My parents never told me they were proud of me. I knew they loved me, but they never acknowledged my accomplishments.”

Lulu steps tentatively onto my lap. The weight of her is negligible, especially compared with my tortoiseshell, who weighs fifty percent more. I do not move, do not look at her. I hope she’ll settle on me.

Lee continues talking about parenting: her mother’s lack of validation of her advocacy award, and her perception that her parents didn’t know what to make of her.

Suddenly she turns her face away from me.

I ask, “What happened just then, when you turned away?” I thought I had seen tears in her eyes.

“I have never seen her get in anyone’s lap,” Lee says. Lulu is lying down in my lap, and I am stroking her.

I’m uncertain what Lee feels, whether she is hiding her feelings about her parents, or jealous of the cat choosing me, or something else altogether. It feels like a big moment, either a breakthrough or a disaster, bonding or retreat.

“She probably smells my cats,” I say.

Lee shakes her head. “No, she likes you. She feels at ease.” I am ridiculously pleased; like most cat lovers, I crave feline attention. To have won over this lovely cat builds my confidence—and then I realize that perhaps there is more going on here clinically. Perhaps in addition to my projection on the cat—that she has chosen me, and I am therefore special—there may be some projection on Lee’s part as well. Perhaps to Lee, the cat’s behavior is evidence that I am okay. Maybe even worthy of trust.

“I wish my parents had told me they approved of me.” The 72-year-old woman looks abashed when I meet her eyes. “I know that I should be over that by now,” she says, “but I think it affects how I act with other people. I am so—” There’s a long pause.

“Self-conscious, maybe?” I ask finally. “Uncertain what other people are thinking about you?”

She meets my eyes. “Yes, exactly. I never know what people think of me. And I always assume it’s bad, bad or nothing at all.”

Before I can respond to Lee, Lulu jumps off my lap, and we hear her hop into the litterbox in the next room.

Lee says again, “I can’t believe she got in your lap.”

After a moment she goes on. “She can’t sit in my lap. I don’t have a lap.” She gestures to her folded pant leg. There is no lap on that side. “She can’t jump into my lap.”

“Do you ever hold her?”

“Yes, I can pick her up and hold her in my arms against my chest. If I lift my foot up a bit, I can even make a lap on this side, but it’s too tiring to keep my foot up.”

I look at her. “Could you put something on the footrest of the chair, under your foot?”

She looks at me. “I never thought of that! Sure, I could put a pillow or a book under my foot. I could make a lap for her—I can’t believe I never thought of that!” Her laughter fills the room.

“Collaboration,” I say mildly, and she gives a small nod.

“I wonder—” I hesitate. “I wonder if your parents might have thought that children don’t need a lot of praise or validation, and that to give it to them—”

I pause a second, and she finishes the sentence: “To praise them might spoil them,” she says, from her own understanding of her parents. I nod, and she goes on. “I never thought about that, but yes—they were eager to avoid spoiling us, or having us get ‘a big head.’”

“Which these days might translate to a healthy ego,” I comment, and this time we laugh together.

“Children do need praise, and validation for their experiences—otherwise we end up feeling weird, or different, or even defective.” I look at Lee and find her eyes on me.

I take a breath for courage and go on: “I was diagnosed with diabetes at 10, and I was so anxious to not be seen as different from other kids, that I kept it a secret as much as I could. Secrets aren’t good for children. They don’t lead to truly healthy egos.”

Our gaze is steady as we both return to childhood. Two little girls reflect each other. Lee smiles at me, one of her first smiles. “I hadn’t thought about my parents’ behavior that way before. It’s helpful to see that maybe it wasn’t about me, so much as what they thought children needed.”

“Yes. And earlier you identified something you know you need now—a friend. It’s not too late for that. We’re building a relationship, you’re going to make a lap for Lulu—you’re trying new things all the time!”

Lee looks a little skeptical, but as I put on my coat, she tells me that when I leave, she’s going to put a big book under her foot. As I drive home, I picture Lulu settling into her lap to purr.