Sympathy for the Deviant

The intense stigma surrounding child sexual abuse clouds an already misunderstood subject—and may ultimately prevent potential abusers from getting help before they commit harm. One convicted offender shares his story.

By Jennifer Bleyer published November 3, 2015 - last reviewed on June 10, 2016

One Friday evening in September 2009, a pair of detectives showed up at the house of a middle-school gym teacher named Evelyn* and asked to speak with her husband, Eugene. A soft-spoken woman with rosy cheeks and tidy bangs, Evelyn told them he was at the small airport three miles away where he worked as a part-time flight instructor. They wouldn’t say what their inquiry was about, and they asked her not to call him. Always deferential to authority, she invited them to wait inside.

Sitting in awkward silence, Evelyn strained to imagine why they were there. Eugene was a respected member of the community—a former U.S. Navy navigator who, after his enlistment, had become a Methodist minister. He was, by all accounts, a compassionate counselor to parishioners going through rocky times, a generous mentor to young people, a supportive ally of his colleagues, and a caring father to his and Evelyn’s twins, then in their 20s. He was self-effacing and humble—it could take years of acquaintance before he would mention that he once led worship services for President Reagan at Camp David.

Evelyn felt a knot of dread in her stomach. She wondered if this had something to do with a strange brush with the law Eugene had had two years earlier, after he retired from the ministry and returned to his earliest passion, flying airplanes. A complaint had been lodged about inappropriate conduct with one of his flight students, a 14-year-old boy. The boy had told police that when they were flying, Eugene had touched his thigh and, another time, had tried to kiss him. The complaint was referred to the district attorney’s office, which declined to pursue it due to insufficient evidence. Eugene had told Evelyn that it was a misunderstanding—a single-engine propeller airplane is extremely tight quarters and he was just trying to help the boy, who said he had a leg cramp. Still, he was devastated by the accusation and agreed with Evelyn to seek help through a Christian counseling service. He spoke vaguely with a counselor about feeling anxious and depressed.

Evelyn heard a car pull up outside. Trim and silver-haired at 64, Eugene strode in through the garage. He froze when he saw the detectives, whom he recognized from his work as a volunteer chaplain for the police department. The detectives announced that they had a search warrant and collected his cell phone, digital camera, computers, and thumb drive. They asked him to come down to the police station; he opted to go right away. Before leaving, he stood with Evelyn for a fraught moment and told her point-blank that he had had inappropriate contact with a family friend’s 13-year-old son, whom he had taken under his wing in the past year, offering him flight lessons and treating him to special outings. He left, and Evelyn started to wail.

Crossing The Line

“I knew why the police were there as soon as I saw them,” Eugene told me six years later. “I was devastated, but a part of me was also enormously relieved to just be done with this.”

After leaving the ministry, he had begun to notice an attraction to early adolescents that was “totally uncomfortable,” he said. It was a feeling that had nagged at the edge of his consciousness before, a kind of nebulous allure that had never led to any improper behavior. Suddenly, he found himself spending more and more time with certain young teenagers, feeling obsessed with them, and inching toward a line he knew he shouldn’t cross.

“It was progressive,” he told me. “It went from skinny dipping, to sleeping nude, to embracing and searching for a full-blown ‘relationship.’ I did not at the time identify what was going on, but I knew deep down inside that something was wrong. I can’t tell you the number of times I told myself, ‘Eugene, you’re 64. What are you doing looking for a relationship with a 13-year-old?’ But it was like being an alcoholic where the drive for pleasure becomes overriding. And where could I go for help? Whom could I trust? I knew how society views pedophiles. I was already full of shame, and those kinds of stories only fueled my shame more.”

When Eugene showed up at the police station, the accusations were enumerated: The boy in question had told authorities that on several occasions when the two were “camping” inside a tent in a hangar at the airport, they had slept beside each other while Eugene was completely nude, and Eugene had touched the boy’s buttocks. The boy also said that Eugene had taken photographs of him in just his underwear and a shirt—pictures that were discovered on the thumb drive. After confirming the allegations, Eugene was arrested and charged with indecent assault, indecent exposure, and corruption of a minor.

Reports of his arrest were soon all over the local news. His friends and colleagues at the airport were stunned, as was everyone at his church, where he was a Sunday service regular and an active member of a Bible study group. Released on bail, he shuttered himself in his house and descended into nearly suicidal despair. Evelyn also became depressed. She anguished over why she hadn’t more clearly recognized that something was amiss and intervened. “I saw that he was spending more and more time with particular young people, and in some ways it seemed like an obsession,” she told me. “But I had no clue what it was. You think the best of people until you find out differently.”

The police, meanwhile, reopened the investigation sparked by the first boy, which resulted in an additional corruption charge. Authorities also pressed the second boy for more information, which turned up new accusations of oral sex and masturbation, bringing even more serious criminal charges. In December, the district attorney held a televised press conference asking for anybody else whose child may have had contact with Eugene to come forward. “It’s a sobering warning to all parents in our community,” he said. “Know who your children are with, because predators like this are out there.”

Who, Why, How?

Few crimes elicit as much moral outrage as child sexual abuse. Long shrouded in silence, it began to emerge from the shadows in the 1980s, as an increasingly confessional culture spurred survivors to speak out. For the first time, both its prevalence and its adverse effects became apparent. The pendulum of public concern swung hard in the direction of indignation, as sexual abuse went from being largely ignored to intensely condemned.

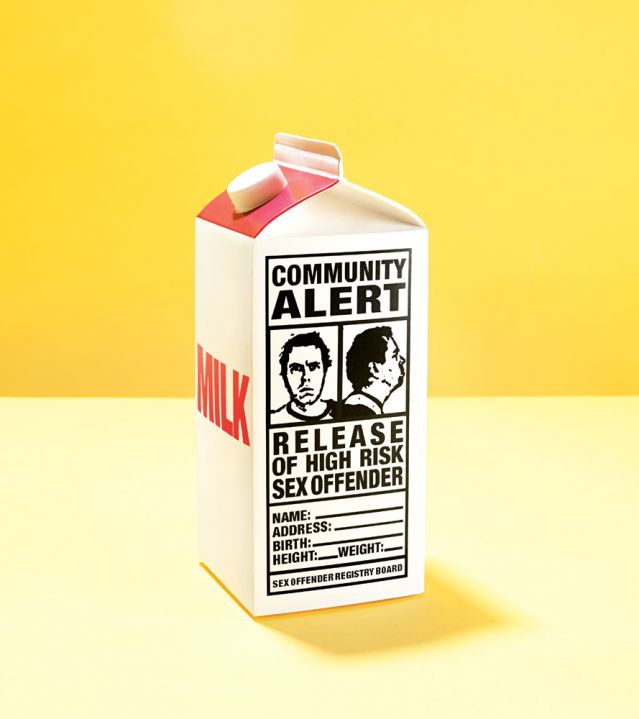

A series of sex-offender management policies were instituted across the country, mostly in response to a few grisly, sexually motivated child abductions and murders that captured headlines and terrorized parents. Such crimes are exceedingly rare, yet the extreme fear they provoke made it easy for policy makers to create public sex offender registries and pass ever-tightening restrictions on offenders in the hope that these strategies would make children safe.

Critics contend that such policies have fueled a mostly unwarranted fear of strangers, and obscured the visibility of sexual abuse where it primarily occurs: in 95 percent of identified cases, at the hands of someone trusted and well known to the victim; a third of the time, by a member of the child’s own family. “Sex offenders are in fact people all around us,” says Elizabeth Letourneau, director of the Moore Center for the Prevention of Child Sexual Abuse at Johns Hopkins University. “It’s very easy to call them monsters, but doing so literally blinds us to when the people in our lives are engaging in inappropriate behaviors.”

Critics also claim that the safeguards have fueled the misperception that sex offenders are uniquely unstoppable. In reality, recidivism rates for sex offenses are lower than for all other major types of crime and much lower than commonly believed. The Department of Justice has found that only about 3 percent of child molesters commit another sex crime within three years of being released from prison, and meta-analysis of hundreds of studies has confirmed that once they are detected, most convicted offenders never sexually reoffend.

There is no simple explanation for what triggers such behaviors. Pedophilia is part of the answer, although only about 40 percent of convicted sex offenders meet the diagnostic criteria for the disorder, which is characterized by an intense, recurrent, and involuntary sexual attraction to children, and which may have biological origins in some cases. Pedophiles have been shown to be shorter on average and are more likely to be left-handed, as well as to have lower IQs than the general population. Brain scans indicate that they have less white matter, the connective circuitry in the brain, and at least one study has shown they are more likely to have suffered childhood head injuries than non-pedophiles.

Whatever its source, researchers emphasize that pedophilia refers only to an attraction to minors, not to a behavior. “There are people who have the disorder of pedophilia but do not molest children,” says Jill Levenson, an associate professor of social work at Barry University in Florida who treats and studies sex offenders. “I’ve certainly met people who have resisted acting on these sexual interests because they know it’s wrong, they don’t want to harm children, and they understand how it will affect their own families and the families of victims.”

For most sex offenders, the impulse to abuse emerges from a murky tangle of environmental, social, and psychological threads rather than, or in addition to, pedophilia. Levenson points to alcohol abuse as a means of comparison. “We know that not every person convicted of drunk driving meets the criteria for alcoholism,” she says. “There are people who might have a lapse in judgment or maybe a discrete period in their life where they were using too much alcohol to deal with their problems. The same is true with sex crimes. There are a variety of reasons why they happen, and not all of them are about sexually deviant interests.”

One such reason is that many abusers suffered sexual abuse themselves as children, which can act as a conditioning experience in their sexual development. Others have behavioral regulation problems, and their compulsiveness can extend toward child abuse if the situation presents itself, even if they are not normally attracted to children. And many, research has shown, have pronounced feelings of humiliation, rejection, inadequacy, fear, guilt, and low self-esteem, and they abuse as a maladaptive way of dealing with their own painful emotions.

“There’s often a cascade of negative events,” Letourenau says. “We see this with teachers a lot, where things are going poorly in other areas of life, and something causes them to doubt their self-worth, and then they’re spending more and more time with kids who have this unqualified adoration and caring for them, and they convince themselves they’re falling in love. It doesn’t seem to be a preferential attraction. Circumstances arise that are very idiosyncratic to a particular situation.”

As his troubling urges brewed, Eugene was too ashamed to breathe a word about them to anyone. The only silver lining after his arrest, in fact, was that he finally felt free to open up. He saw a clinical psychologist for six months, during which time he came to realize that while he still loved Evelyn, they had grown apart to the point of leading parallel lives, leaving him emotionally adrift. He recognized how the firm institutional boundaries of the military and the church had kept him from crossing a line earlier, whereas as a flight instructor he was faced with a level of proximity and privacy with kids that he had never experienced before. Their innocent admiration of him as a talented pilot felt intoxicating. Perhaps most important, he examined his upbringing in a strict, religious family and the deep insecurity instilled by his verbally and emotionally abusive father.

“I was only afforded time to scratch the surface, but it was very helpful,” he says. “I wish I’d known even a small part of what I learned in my brief time in counseling before I did what I did.”

Levenson says that while there are countless routes to sexual offending, and the majority of men with low self-worth are certainly not destined to become child molesters, there’s often a common denominator in men who feel fundamentally bad about themselves and go on to develop close emotional connections with minors.

“Many don’t have very good avenues for self-esteem, and they seem to fall in love with a particular child who makes them feel special and important and doesn’t have the same kinds of expectations and judgments an adult would,” she says. “I’m not excusing or condoning it, but it’s important to realize that the pathway is really similar to the way the rest of us experience relationships. It’s about emotional intimacy that gets sexualized.”

Most offenders are stopped only after they’ve careened all the way down that path and children have been harmed. The challenge from a prevention perspective is both to recognize that arriving at that point is not inevitable, and to offer secure off-ramps before they get there.

“Things don’t ‘just happen,’” says Charles Flinton, a forensic psychologist in San Francisco who provides court-mandated therapy to sex offenders and conducts evaluations to determine their risk status. “It builds up over time. Let’s say somebody finds himself sexually attracted to children. He may start by looking at magazines or catalogs with kids in bathing suits. He’s a little nervous, and then he becomes desensitized to that nervousness. He may start creating arguments in his head that it’s OK to put himself in situations with kids or to prepare children to be more comfortable around him in what would otherwise be awkward situations. With each step, he moves toward offense behavior. Most are able to identify a point at which there’s a fork in the road.”

Unlike other kinds of risky behavior, however, the secret nature of their attraction leaves no opportunity for intervention, let alone empathy for whatever internal struggle they may be engaged in to control themselves. What’s more, the profound stigma that surrounds sexual attraction to children actually ends up abetting the very behavior it stigmatizes, amounting to a catch-22 with abhorrent consequences. “People with a sexual interest in children don’t have any reality check to bounce up against,” Flinton says. “We engage in sexual decision making, as with any decision making, by communicating and interacting with others about our dilemmas. But these people are totally isolated, which only increases their risk of acting out. They become entrenched in a double life that’s hard to escape.”

The isolation is ultimately more dangerous than the feelings themselves, says Joan Tabachnick, co-chair of the prevention committee of the Association for the Treatment of Sexual Abusers. “Sex abuse thrives in isolation, and shame sets the isolation in concrete,” she says. “If we can begin to break apart that shame and isolation, we’ll be much more likely to intervene earlier in the cycle. The environment that allows sex abuse to thrive would be eroded.”

The Ripple Of Stigma

In March 2010, Eugene appeared before a judge at the county courthouse and accepted a plea agreement. He was sentenced to eight to 20 years in prison. He was also designated a sexually violent predator—based on a 12-minute interview with a forensic expert—which means that after his release, at age 73 at the earliest, he will be on the sex offender registry for the rest of his life.

Gathered in the courtroom were his family and friends, including fellow pilots and Methodist clergy who had known him for decades and who testified that while his crimes were indefensible, and their hearts ached for his victims, the Eugene they knew was a fundamentally virtuous person who had done incalculable good in the six decades prior to his offenses and had, one friend said, a “deep desire to defeat this illness.” The last to stand and speak on his behalf was Evelyn.

“I could have easily abandoned my husband, like some would,” she said. “Our family stands by his side today because of a lesson I have learned in life. We all make mistakes. We all have compulsions. We all have a side of us that we’re afraid to show others, and we all need compassion and forgiveness.”

The dense mass of stigma surrounding sexual abuse not only deflects compassion for potential abusers but it erects particular barriers that prevent them from getting help. Levenson surveyed convicted offenders about these barriers, and “the first thing they say is that they really had no idea where to go,” she says. “They see all these public health announcements: ‘If you have a drug problem, or a gambling problem, or you think you have HIV, call this number.’ But you never see a bus go by with an ad that says: ‘If you’re concerned about your attractions to children, call this number.’ Another reason is the very shame and fear of judgment—‘If I open up and tell somebody, what are they going to think of me?’”

People attracted to juveniles also internalize the message that they can’t be cured. “When they open a newspaper or turn on the TV, they hear the same message that you and I do—that sex offenders are monsters who will always reoffend,” Levenson says. “Are there people who are attracted to kids? Yes. Can we change that attraction? For some, no, although they can choose not to act on it. But if somebody believes he can’t be cured, he’s not going to ask for help.”

The final obstacle cited by almost everyone is the very real fear of legal consequences. Mandatory reporting legislation requires certain licensed professionals, including doctors, teachers, psychotherapists, and social workers, to report suspected cases of child abuse or neglect to child welfare authorities. The laws are federally mandated, and although they differ somewhat among jurisdictions, the intent and requirement are the same everywhere and have a clearly good purpose: to protect children from harm. In many states, the failure to report is a misdemeanor punishable by imprisonment and fines.

Mandatory reporting laws are credited with facilitating a decrease in all kinds of abuse and neglect over the past several decades. In the case of sexual abuse, however, they have had the inadvertent effect of making it very hard for someone who is attracted to children, and who may even be inching along the pathway toward abuse—by looking at child pornography, for instance, or touching a kid’s thigh, as Eugene did—to ask for help without risking the infamy of being identified. “Self-preservation steps in,” Levenson says. “Even if they’ve never acted on them, men who are concerned about their attractions are reluctant to seek counseling, because they’re afraid they’re going to be reported.”

Even admissions that fall within the limits of confidentiality in psychological treatment are seldom voiced because of confusion and fear. “If someone comes in and says, ‘I’ve been looking at pictures of children in bathing suits in a Macy’s catalog,’ that’s not usually something that would have to be reported,” Levenson explains. But the actual details about what requires a report—in many states, an identifiable child has to be endangered—tend to be overlooked within the overall climate of vilification and punishment, she says. People are terrified to admit to anything, whether or not their admission would really necessitate a report. “There are absolutely people who have started down the road of offending who want to stop,” Letourneau says. “They don’t get help, because between mandatory reporting and lifetime sex offender registration, the consequences are too much to bear.”

Safe Off-Ramps

When clinicians consider what an effective prevention approach to sexual abuse might look like, many point to an initiative in Germany called Prevention Project Dunkelfeld. Begun in 2005, the program aims to prevent abuse by offering anonymous treatment to people who are sexually attracted to pubescent and prepubescent children. The program is advertised in slick media campaigns. In one TV spot, a series of masked men in varied dress—a suit and tie, a tracksuit, a grandfatherly sweater vest—recite a script of internal dialogue: “It’s obvious what you think of the likes of me. Sicko! Pervert! Scum! I thought so too. In therapy I learned that no one is to blame for his sexual preference, but everyone is responsible for his behavior.” The last man removes his mask, revealing a typical looking guy. “I don’t want to be an offender!” he says.

Over 5,000 people have come forward seeking services, and there are now 11 Prevention Project Dunkelfeld clinics in Germany, which use cognitive behavioral methodology to teach clients how to control their sexual impulses. The clinic also offers psychopharmaceutical interventions, including, when needed, testosterone-lowering medication that dampens sexual appetite. The project’s initial results are based on very small samples but appear encouraging: Participants have been shown to experience improvements in their self-regulation abilities and decreases in attitudes that support sexual contact with children. More critical, Letourneau says, is what’s indicated by the sheer fact of those who’ve reached out for support: “That you have this group of people who may have been white-knuckling it themselves, and who are willing to identify as wanting and needing help, supports at least the promise of prevention.”

Controversially, however, there are no mandatory reporting laws in Germany, so even someone actively abusing an identifiable child can get help and remain anonymous. Nobody seriously proposes doing away with mandatory reporting in the U.S., although some think it should be modified to encourage people to get help much earlier in the offense trajectory. But even if help were possible to pursue, it’s unclear where one would get it. As Levenson points out, there are no public service announcements pointing to resources for dealing with such urges. And mental health professionals, fuzzy about their own legal obligations and nervous about their liability, have been known to shirk potential clients who want therapy.

“A lot of sex offenders I’ve worked with knew they had a problem before they acted out illegally; they sought assistance and were turned down,” Flinton says. “Therapists reject them, saying, ‘I can’t work with you’ or ‘You can’t tell me this.’ It’s infuriating, really, because a crime could have been prevented, and these guys could have ended up living productive lives.”

In recent years, Flinton has himself been contacted by more and more men in this position: “They call me saying, ‘I’m having sexual fantasies about children, and I don’t want to—what do I do?’ Or it’s often their wife or girlfriend who calls out of concern. They say their partner isn’t really present, that he’s missing a lot of family time or spending hours a day looking at pornography and seems to be building a double life.”

In 2013, Flinton opened a Bay Area clinic called the Blue Rock Institute. Although the clinic has received only about 100 clients so far, it represents a hopeful example of what proactive prevention of sexual abuse could look like. While vigilant about making mandated reports when required, the clinic primarily reaches men who describe deviant fantasies, but who haven’t yet crossed the line of illegal behavior. The treatment model is very similar to interventions for addiction: As with substance abuse, Flinton explains, sexually abusive behavior is often something people engage in to suppress negative feelings. The clinic’s therapeutic focus is on addressing the underlying source of those feelings, many times in family dynamics or early traumatic experiences, as well as on helping people work past their shame, comprehend how distorted thought patterns can reinforce unhealthy sexual behavior, and learn how to meet their needs in healthy ways.

“We want these guys feeling safe to look at themselves and understand their problem,” Flinton says. “They often have a lot of internal strengths. It’s about identifying those and capitalizing on them, while still holding the men accountable. Our goal is to prevent victims. You have to get these guys in the door to be able to do that.”

After he was sentenced, Eugene spent two years in a county jail before being moved to a large state penitentiary. Evelyn travels two hours to visit him there once a week, and on a dazzling summer morning, I went along with her. We drove on a narrow road lined with strip malls and industrial facilities until we arrived at a vast expanse of manicured grass and dogwood trees that brought to mind a college campus. At its center was a complex of boxy buildings surrounded by towers of barbed wire.

Eugene, in a maroon jumpsuit and wire-rim glasses, beamed when he walked into the visitation room and saw Evelyn. They kissed and hugged tightly. “He’s still the same person I married 33 years ago, the same person I know and love,” she said. “Just the fact that we can talk about what happened is a step in the right direction. If we’re not able to talk about it, there’s no way to change.”

They made the rounds of the room’s vending machines to gather their usual visiting day provisions—pretzels, chips, shrink-wrapped deli sandwiches, sodas—and we settled into a corner to eat. Eugene spoke with enthusiasm about his job as an inmate assistant in the prison’s sex-offender therapy program. Having completed the program himself, he now works with a staff psychologist several days a week, helping facilitate group sessions in which other offenders detail their offense trajectories, do exercises to cultivate empathy for their victims, learn behavioral-modification techniques, and craft relapse-prevention plans. In listening to their stories, and ruminating on his own, he has developed a certain zealousness for the need to reach people before they do the things that land them in prison.

“I take full responsibility for my actions,” he said. “Yes, I am a sex offender. Yes, I live with this desire and will live with it for the rest of my life. But surely it must be possible to construct some sort of framework of help for men like me that does not end with victims and prison.”

One place where such a framework is being attempted is in his own church. Eugene’s face reddened and tears glazed his eyes as he told me about a recent phone call with a church officer in charge of an effort to extend confidential support to clergy coping with an attraction to children—an effort that was galvanized in the eye-opening aftermath of Eugene’s transgressions. The church officer told him that a minister and a ministry student had recently come forward for counseling. “Hearing that makes this all worthwhile,” Eugene said. “If my story can in some way help prevent some terrible offense, then the journey has been worth it.”

*The couple are referred to by their middle names.

Submit your response to this story to letters@psychologytoday.com. If you would like us to consider your letter for publication, please include your name, city, and state. Letters may be edited for length and clarity. For more stories like this one, subscribe to Psychology Today, where this piece originally appeared.