Turning Back Time

Faced with the prospect of loss—in our natural environment, of our legacy of language, and even on our computer screens—diverse preservationists are rebelling against inevitability and saving what we value most deeply.

By Diane Cole published May 4, 2015 - last reviewed on June 9, 2016

What happens when one’s comfortable surroundings become only discomforting reminders of loss?

That’s the question philosopher Glenn Albrecht began confronting a decade ago as he interviewed fellow Australians about changes rendering their local environments suddenly unrecognizable. In some areas, scenic vistas had become dusty, barren, coal-mined pits. In others, sustained drought had left once-arable farmland parched, setting off an eco-chain reaction affecting backyard gardens and birds that would no longer fly and sing overhead. Their disconsolate voices reminded Albrecht of those of indigenous peoples who had been forcibly removed from their native lands. But his interviewees had never left home.

Albrecht coined a term to describe this “dis-ease.” He called it solastalgia, evoking a longing for what has disappeared from one’s environment that goes beyond nostalgia to a sense of loss and distress for which there is little solace.

Solastalgia is an existential condition, not a medical one, but it has real mental-health implications. And we don’t experience it only in our natural environment. The loss of traditions, languages, even cherished websites can profoundly affect our psyches. How do we respond to or, if we must, live with the loss? One way is to push back against it—or, as Albrecht would suggest, to push forward, to preserve a future as comforting as our present.

As demonstrated by the following individuals and their colleagues, this impulse can be acted on in realms as varied as ecology, the arts, and the web. Artist Katie Paterson’s work hauntingly evokes the sounds of melting icebergs and anticipates the tactile needs of a paperless society. Linguist David Harrison travels the world to identify and revive languages rapidly approaching their final utterances. Internet pioneer Brewster Kahle acts on an ancient human instinct to preserve knowledge, in both the virtual and physical realms.

From the purely metaphorical to the stolidly practical and even the utopian—and sometimes all three at once—these 21st-century preservationists are securing a link between the past and the future, and showing the rest of us how to look on our changing world not with resignation but resilience.

Katie Paterson: Seeding a Forest of Thought

A year ago, 34-year-old Scottish conceptual artist Katie Paterson embarked on Future Library, a 100-year art project that she almost certainly won’t see reach fruition. It’s a long-term projection into the future—a hope, an expectation, that humans will still be here to greet, appreciate, and connect with the culture of the past that launched it.

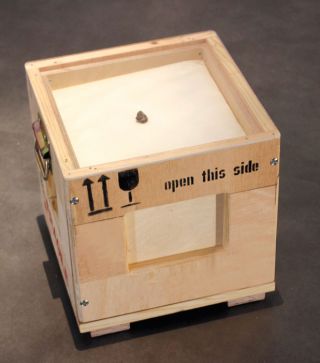

For the project, 1,000 trees have been planted in a forest outside Oslo, Norway. A century hence, paper from those trees will be used to print 100 as-yet-unwritten books—which, by 2114, may have become rare objects.

“We’ll be cultivating something every year,” Paterson says of the project, which is perhaps best envisioned as a living time capsule that will re-create itself until its completion. Each year, a different author will contribute an original manuscript, which will remain unpublished until the paper is ready. The first contributor is Canadian novelist Margaret Atwood.

Establishing a grove and a library of original, paper-based books for 22nd-century audiences may seem like taking the long view for an artist, but for Paterson, the timespan is actually fairly puny. Another recent work, Fossil Necklace, represents millions of years. At first glimpse, it is an elegant piece of jewelry composed of unusually diverse multicolored beads, some shimmering and others streaked with color, oddly milky, or with marbled interiors. But look again: The 180 beads are actually fossils she collected from all over the world, each representing a geological or evolutionary phase, with its origin detailed in an accompanying diagram. “Every fossil was so exquisite,” she says, each appearing to be a distinct planet or micro-universe. Using the chart, one can discover, say, a polished, fossilized bit of bison bone from Siberia, dated from the Pleistocene—the era when modern humans first appeared in that region.

Paterson is known for works evoking and linking time, space, and ecology through unexpected juxtapositions. Her 2007–08 installation, Vatnajökull (the sound of), for instance, consisted of a white neon sign with a cell phone number which, when called from anywhere in the world, connected to an underwater mobile phone and amplifier submerged in an iceberg-laden glacial lagoon in Iceland. Anyone who dialed in could hear what a glacier in retreat sounds like—the crackly snaps, pops, and splashes of ice melting, breaking off, and crashing into the surrounding water.

Paterson lived in Iceland for seven months when she was 23, and she cites the island’s continued impact on her work. “The wilderness, the light, a landscape embedded in time—you can see the strata and the time everywhere, from the layers of lava and the glaciers and the melty dimensions.” That sensibility is reflected in another project, in which she recorded three separate glaciers, had the sounds pressed into records made of frozen melt water, and let the discs melt as they played on turntables.

For Earth-Moon-Earth (Moonlight Sonata Reflected from the Surface of the Moon), she transformed the familiar tones of Beethoven’s famous work into Morse code and bounced the result off the moon via radio waves. The audio that came back to Earth—translated back into music and played by an automated grand piano—was mostly recognizable yet eerily off kilter, the result of notes and chords altered and lost among the irregular craters of the moon in the process of transmission. In these and other pieces, she says, she connects “the vast and intangible with the everyday.”

“Nature recycles itself constantly,” Paterson says. Her artistic sensibility unnervingly combines wonder and awe with a stark recognition of being lost in the universe. “One thing might seem like a death to a human being, but it’s a continuation of life in the universe from a more cosmic perspective.”

The passage of time through nature and the universe is made present in all of Paterson’s work, as is what’s lost in the process, despite our efforts. “I’m taken with a Japanese phrase, mono no aware. It means something like a nostalgic sadness connected to the vanishing of the world,” she says. “I’m capturing the natural beauty of things and also mourning the loss of something that’s passing. There’s this feeling of hope that we’re trying to build for the future, but also a lot of darkness, with the question: Will there be a future?”

Another project, All the Dead Stars, looks even more deeply to the past. In it, Paterson mapped the locations in the sky of nearly 27,000 stars, the deaths of which have been recorded and observed by humans. “I’m taken by the sublime nature of looking at a star dying,” she says. “The remnants given off also build new planets and new life.”

Her map, she believes, “is like a graveyard of stars, but it also describes a place of constant recycling. It’s destruction and self-destruction and self-regeneration—the way that something always becomes something else.”

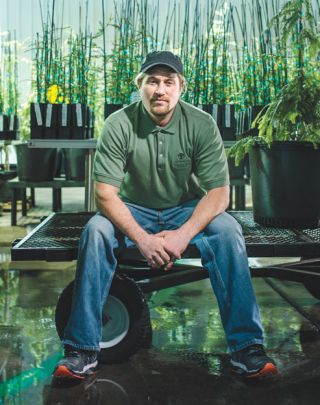

Jake Milarch: Making Roots Mobile

“My family has deep roots with trees,” quips fourth-generation tree farmer Jake Milarch, 33. When his great-grandfather witnessed the felling of large swaths of trees to make way for factories in early 20th-century Michigan, he started replanting trees as part of his business. Today, from the windows of his home outside the tiny town of Copemish, Jake looks out on an expanse filled with so many types of native and imported trees—including sugar maples, ponderosa pine, pintos, beech, and others—that he likens it to a botanical zoo. Through the profusion of trunks and branches, he can see the house once occupied by his great-grandfather and now home to his nonagenarian great uncle, who also made his living planting and maintaining trees.

And yet, Jake says, he sometimes wonders “if I will be the last one left looking at this landscape.”

He pauses at that painful thought, but his tone quickly turns buoyant as he begins to talk about what he and his family are doing to make sure that doesn’t happen.

Their work goes forward through the efforts of the Archangel Ancient Tree Archive, a grassroots nonprofit organization whose guiding spirit is Jake’s father, David Milarch. In 1991, David emerged from a near-death experience with a newfound determination to use his generations-old forestry skills not only to preserve and protect the world’s giant, old-growth trees but also to restore them to the vast landscapes where they once thrived, since denuded by decades of intensive logging. These so-called “champion trees” include coast redwood and giant sequoia—awe-inspiring specimens that can grow to 200 to 300 feet or higher, with natural lifespans measured in centuries and even millennia, although more than 95 percent have been cut down.

Archangel’s mission is to locate the remnants of the world’s still-living endangered old-growth trees, clone them via horticultural techniques both traditional and high-tech, plant these offspring to reforest the earth—and in so doing, help to reverse climate change. So far, 70,000 such trees have been planted in seven countries.

For Jake, “it’s in the family sap” for him and his older brother, Jared, to be just as involved with tree restoration as their dad. Along with his field work, Jake oversees Archangel’s education program, including open houses, school visits, and hands-on teaching. “Imagine if we planted 50 trees,” he says, “and then taught our friends and children to plant 50 trees. Imagine what we’d have.”

“There are truly very few landscapes not disturbed by man,” Jake says, “and to find these trees you have to go very far.” And also high. He has climbed to the crowning canopies of 300-foot-tall giant sequoia and redwood trees in California and elsewhere to acquire precious cuttings that he rushes back to the nursery/laboratory in Michigan. There he acts as a “surrogate mom,” he says, attending to cuttings as if they were “preemie newborns,” making sure to adjust the moisture, temperature, light, and other environmental factors that will allow them to grow.

Using such techniques, the Milarches have even been able to clone trees cut down long ago, but from whose stumps they can still capture living basal sprouts. That was the case with the Fieldbrook coast redwood in Humboldt, California. More than 32 feet in diameter, it was cut down a century ago to settle a bar bet, at least according to local legend. Genetic duplicates from that tree were among the 1,000 coast redwood saplings Archangel shipped in mid-February for planting near coastal Bandon, Oregon.

Reforesting the world from the preserved genes of lost trees is a job that will take more years and manpower than the Milarches can provide in their lifetimes. But Archangel is armed with what the group calls a living library of 70 cloned champion trees with material to keep the group active worldwide for generations to come. The collection of clones, Jake says, “is our ultimate weapon for paying it forward for future generations. What a gift to give—something that can live for 3,000 years or more.”

K. David Harrison: Hearing What Few Others Can

Endangerment. Extinction. Revitalization. Most of us associate these words with threatened living species. But for linguist K. David Harrison, those words also apply to the life—and death—of languages.

A professor at Swarthmore College and director of research for the nonprofit Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages, Harrison has journeyed to some of the remotest areas of the world—in Siberia, Mongolia, Chile, and Papua New Guinea, to name a few—seeking out and listening to men and women who are among the last speakers of their languages. His quest: Record, document, and, if possible, help revive languages that, not so long ago, were everyday currency of communication in their native regions but today may be spoken or remembered by only a few thousand, or just dozens.

More than half of the 7,000 languages spoken in the world today will be extinct by the end of this century, Harrison believes. To highlight those most at risk, he and his colleague at the institute, linguist Greg Anderson, charted the world’s linguistic hot spots, pinpointing regions where language diversity was most endangered and where native tongues were also the least studied.

The way we speak is intrinsically tied to who we are, how we live, and how we experience the world. The loss of any language, then, goes well beyond vocabulary. “Our ways of seeing things and doing things are not the only way,” Harrison asserts. To give one small example, he says, “The Tuvan language [of southern Siberia] conceptualizes the past and future as the opposite of how we do in the West.” They speak of the future as being behind their backs, while the past is in front of them; when we speak of the future, our hands inevitably point forward.

“But so what?” Harrison asks rhetorically, aware that some see a single global language as ideal, if not inevitable. “Wouldn’t it be better if people just spoke the same language? No. Languages provide different ways of understanding. The human intellect is vast and adaptive and creative and does not employ the same thought processes in every culture.”

Our diversity of language reflects the diversity of the planet itself, he says. When we lose one, that diversity is irreparably harmed. “The extinction of ideas we now face has no parallel in human history,” he writes in his book, When Languages Die. “Since most of the world’s languages remain undescribed by scientists, we do not even know what it is that we stand to lose…an accretion of many centuries of human thinking about time, seasons, sea creatures, reindeer, flowers, mathematics, landscapes, myths, music, infinity, cyclicity, the unknown, and the everyday.”

To push back against solastalgia-inducing trends of economic development, as well as the globalization of language, Harrison and his colleagues enlist the very tools of global connection against it. Their online Talking Dictionaries archive offers online recordings of many endangered languages, featuring native speakers pronouncing words, reading sentences—and singing songs. Yes, visitors from around the connected world can access the archive to gain a feel for a language and its culture, but local community members also come online to learn, or relearn, their native tongue.

The video-streaming site Viki works with the institute to facilitate communities’ subtitling shows from all over the world into their languages. And in performances recorded at the annual Smithsonian Folk Life Festival, which Harrison helped curate two years ago around the theme of greater awareness of endangered languages, featured speakers, musicians, and poets put their cultures on stage for a global audience.

Harrison rejects the “preservation” label for his work: “That sounds like keeping something in a jar.” He’s more interested in revitalization. “I don’t save the languages,” he says. “That can be done only by the speakers.” When he helps a group assess the state of its language, including how many speakers remain, he says he asks, “What does the community want to do? What is their vision? Do they want to cross the digital divide and have an Internet presence? A book in the language? The stories of the elders recorded and kept?”

“A constant theme I hear from these communities is identity. Their language and traditions are an integral part of who they are, and they feel at loose ends when they lose those things. It does not mean they are backward or not modern,” Harrison says. “For centuries they’ve been told to assimilate, to get with the program, and it’s a push-back now against this.”

“Change is inevitable, and living languages are constantly changing,” he says. “I accept the idea of globalization and that people want to learn English. But I don’t accept people being coerced into giving up languages because they are considered not suitable. You can

still be bilingual—have your heritage language and a global language—and be smarter for that.”

Brewster Kahle: Archiving at Broadband Speed

In its day, some 2,300 years ago, the Library of Alexandria was the physical repository of the collective writings and wisdom of an era. Then it burned.

The very works the grand structure had been built to preserve were all lost, and a treasure trove of knowledge vanished forever.

Alexandria offers a lesson in preservation that is not lost on Brewster Kahle, the digital librarian and World Wide Web guru best known for his creation of the Internet Archive, our modern-day virtual equivalent of Alexandria’s ancient edifice. We lost the masterpieces of the ancient world not just because the library burned, he believes, but also because there were no duplicates. His mantra: “Don’t have just one copy. Archive them at multiple places. And preserve them well.”

That’s the mindset behind Kahle’s virtual archive—an astonishingly broad online library, from whose entry portal anyone can gain free access to massive collections and knowledge bases that go beyond archived commercial web pages to include digitized texts, music recordings, moving images, and software.

All of these data need to be archived now, Kahle insists, because even though web pages can’t be physically burned, they do disappear. And with astonishing speed.

“The average life of a web page is about 100 days before it is changed or disappears,” he explains. Adding to the Internet’s vanishing act is the fact that “there are services such as Geocities, Google Video, and any number of others that shut down. They closed forever. You trusted your [material] to what looked like a major site supported by a major corporation and then it just goes away.

“We’ve poured our lives into the web,” he says. We’ve done so much reading, commenting, posting, sharing, blogging, researching, playing, and back-and-forthing with everyone we know (and millions of others we don’t), that the web now contains the very stuff of our lives.

But when a website that had come to seem like second home is, suddenly, no longer there, the pain and the dislocation represent no less a shot of solastalgia than the loss of a cherished scenic outlook. What you had thought was permanent turns out to have been as ephemeral as the air itself.

Even sites still in wide use constantly undergo change, or become accessible only through paid subscriptions. “Sites shift,” Kahle says. “When we want to refer back to what we were reading, it is often gone.” And so are those parts of your past, your memory, and your sense of place that you had trusted would always be there.

Kahle launched his Internet Archive back in 1996, with an ongoing mission to crawl the web, capture and archive every publicly accessible web page on every site, and then keep on crawling. As of May 2014, the number of Kahle’s archived web pages surpassed 400 billion.

The general-public interface for Archive data is called the Wayback Machine, after the computer used for time travel by Mr. Peabody and Sherman in cartoon shorts from the 1960s TV classic, Rocky and Bullwinkle. By the site’s measurement, as of December 2014, the Wayback Machine contained almost nine petabytes of data—eclipsing the amount of text contained in any of the world’s largest libraries, including the Library of Congress—and it’s growing at a rate of about 20 terabytes per week.

But that’s only the beginning. Kahle seeks to collect not just the Internet’s knowledge but all knowledge that can be collected, in any form. “If all you look at as your library is the Internet, that is not enough,” he says. “The Internet is efficient, but also limited. We need to put the best we have to offer in front of our children. And right now if it’s not online, it’s as if it doesn’t exist. So we’d better do what we can to put the best information online and make it available to everyone, or else we get the generation we deserve.” To fill the gap, Open Library, another initiative of the Internet Archive, is digitizing 1,000 books a day and making millions of books available to “borrow” and read online.

Kahle’s motivation is not only to preserve. “One of the things that motivates me is that I have a terrible memory, clinically bad,” he says. “Institutions like the Archive are trying to save for the world something I would like to have. I want to actively augment my memory; we have the opportunity now to have machines help us do that.”

A Silicon Valley legend, Kahle’s ideas helped create the virtual world we all populate in some way. But having witnessed the rapid evolution of technology, he knows better than most that we can’t rely on a single format to preserve our knowledge. To that end, the Archive retains multiple physical copies—in different locations—of every book, text, movie, and video it digitizes so that people can refer to the original sources in the future. He wants to make it easy for future librarians to go as far back as he can lead them, even as the world lurches forward.

“I don’t think we should have the hubris to think we’re the last ones to digitize books or to assume that the present formats for preservation” won’t become obsolete, he says. Archivists who don’t learn from Alexandria are doomed to repeat its mistakes. For now, our culture is in good virtual hands.

The Earth's Backup Plan

When I visited the Canadian Arctic in the summer of 2003, I told people that my son and I wanted to get there before it was too late to see polar bears in their natural habitat. Many of my friends thought I was being alarmist, but already, warmer Arctic temperatures had led to disappearing glaciers, and less sea ice meant less territory over which the bears could roam and hunt for food. Their home, in short, was disappearing—melting—around them.

By 2007, when we booked a second trip to the Arctic—this time, to the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard—even more ice had melted. The resulting drop in food resources was probably why one polar bear we spotted looked so thin and undernourished. The real Arctic chill, I now think, comes from the feeling we get from its inexorable shrinking.

But the Arctic, and specifically Svalbard, also stands for preservation. The Svalbard Global Seed Vault, built into the permafrost at the base of a mountain and designed to last 1,000 years, opened in 2008 as the planet’s largest fail-safe agricultural storage facility—the ultimate backup for 1,700 other food-crop gene banks already established around the globe.

The imposing facility—while only its lobby is visible from the outside, its three seed vaults are sited 130 meters into the rock—is maintained by the Norwegian government. It contains some 860,000 seed varieties, but has the capacity to store 4.5 million. There’s even backup for the backup: Each stored variety will constitute, on average, 500 seeds, so a maximum of 2.5 billion seeds of hope may be kept in the vault.

Submit your response to this story to letters@psychologytoday.com. If you would like us to consider your letter for publication, please include your name, city, and state. Letters may be edited for length and clarity. For more stories like this one, subscribe to Psychology Today, where this piece originally appeared.