Memory

Lifelong Learning and Active Brains: E is for Evaluate

The ability to understand what we know is important for learning and memory.

Posted September 2, 2018

How do you know what you know? Psychologists use the term metacognition to describe the ability to evaluate our own mental processes. If a student comes up after an exam and says, "I don't know why I did so poorly, I thought I really knew the material," it clearly suggests poor metacognition. Such "illusions of knowing" can hamper learning, because a student would not feel the need to study further if he or she felt that the material was already well learned.

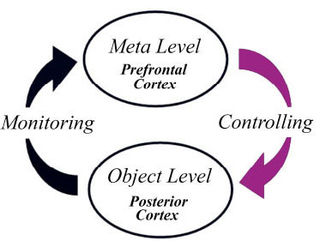

The need to evaluate what we know is the fifth principle of MARGE, our whole-brain approach to efficient learning. Thomas Nelson—one of my graduate school mentors—and his colleagues developed a model of metacognition which helps us understand its importance in learning and memory. As shown in the figure to the left, a meta level monitors and controls object level processes, which are cognitive processes that go on at every conscious moment, including your ability to recognize these words and garner their meaning. Like an orchestral conductor overseeing the musicians and modulating their performance, the meta level oversees cognitive processes and controls future actions.

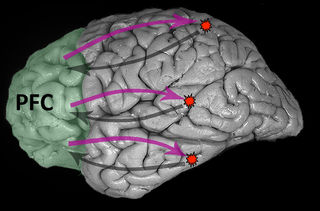

With respect to brain mechanisms, there are parallels between metacognition and the role the prefrontal cortex (PFC) plays in supervising activity in the posterior cortex. Object-level processes can be viewed as neural activity in the posterior cortex associated with cognition (seeing, recognizing, understanding), and the PFC acts as your meta level by monitoring activity via projections to the PFC and controlling them via projections back to the same posterior regions (see figure). Thus, we can connect metacognition with the PFC—both are important for focused attention and executive control.

Why do we sometimes fall prey to an illusion of knowing? Memory researchers make a distinction between two kinds of metacognitive "knowing." There's hard-core knowing, which involves recollection, our ability to state explicitly why we know something, and familiarity, that more diffuse "warmth" feeling of knowing that occurs when something is recognizable but you can't really put your finger on it. To give an example, I was sitting at a coffee shop near campus, and a young woman came up to me and said "Hi, how are you?" I recognized the woman (there was familiarity), but was struggling to place her as I fervently searched through my mental file of former students. The woman noticed my struggles and said, "I'm your next-door neighbor, Aubrey." Of course, my problem was that I was searching in the wrong mental file cabinet (also Aubrey had just moved in a few months ago—my other excuse). There's actually a name psychologists coined for this experience of familiarity without recollection—the butcher in the bus phenomenon—in which we see the butcher on the bus but can't place him because he's out of his usual context.

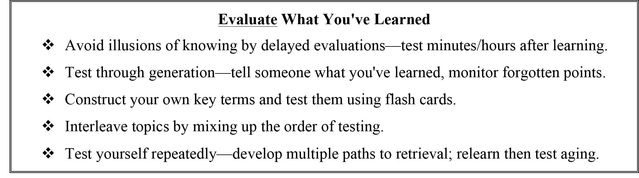

The illusion of knowing often occurs because we have familiarity without recollection. The information feels fresh and recognizable at the moment (i.e., familiar), but that feeling prevents us from a valid judgment of its actual memory strength (i.e., recollection). In one study, individuals were given word pairs to learn (e.g., OCEAN-TREE). For some pairs, they were asked immediately after presentation to rate how well they would be able to remember the second word when cued with the first (e.g., OCEAN- ?). For other pairs, this evaluation wasn't requested until several minutes after learning. When assessed right after seeing the pairs, individuals grossly overestimated their learning ability—they thought they would do well when tested later. This illusion of knowing occurred because the pairs—having just been presented—was still fresh in their short-term memory and thus seemed available at the time. When the evaluation was delayed, that freshness/familiarity was gone and the evaluation reflected better how well they could recall the second word from long-term memory. Thus, one way to prevent illusions of knowing is to wait some time (minutes, hours, days) before testing your memory.

To verify your learning proficiency it is critical to test yourself several times. The easiest way to do this is to apply the generate principle and try to recall material from memory. By telling someone what you know or writing the information down (e.g., as a blog entry), you will soon realize any forgotten points or weakly remembered concepts. You can then go back to sources and revitalize forgotten points. When you evaluate your learning through testing, you accomplish two things—you have generated the information thus strengthening your memory for the material itself, and you've determined missing points or weakly remembered concepts which you can go back, relearn the material, and test again. By testing yourself repeatedly you strengthen memory as you establish multiple pathways to the knowledge.

Learning, particularly in classroom settings, often depends on remembering cued or pairwise associations, such as new terms, definitions, or foreign vocabulary words (e.g., CAT-GATO). A good way to study course material is to generate your own set of key terms (4-6 per section or book chapter) and write in your own words their definitions. You can then give yourself tests with flash cards (virtual versions are available online) in which the cues are presented and you must generate the associate (e.g., CAT-?). To prevent illusions of knowing, be sure to delay the time (minutes, hours, or days) between learning and flash card testing. Just for fun, let's learn six state capital via imagery mediators and later we can evaluate our learning proficiency. Spend several seconds visualizing the images suggested in parentheses: Arizona-Phoenix (a phoenix ARIZing), Nebraska-Lincoln (Abraham Lincoln ASKing you to vote for him), Connecticut-Hartford (a CONman selling hearts on a Ford), Florida-Tallahassee (the tail of Florida on a tall hussy), Kentucky-Frankfort (a Kentucky Derby horse eating a frankfurter), Michigan-Lansing (the two parts of Michigan being lanced together).

Another student learning tip is to interleave your evaluate sessions across subject topics. You may have to learn material across several topics (e.g., book chapters) within a course or even simultaneously have to study material from several different courses. Interleave (i.e., mix up) the order in which you test the various topics at hand. Better yet, truly interleave course material from different sections or chapters by categorizing, comparing, and contrasting (i.e., 3 C's) the entire body of information together. The main thing is to avoid "blocking" or "massing" your learning sessions with just one issue—try to mix it up.

Now test yourself: Connecticut? Michigan? Arizona? Florida? Kentucky? Nebraska? If you can remember the state capital of each, congratulations! If you cannot remember, evaluate your feeling of knowing by rating how well you think you'd get the answer if I showed you some choices. Then, for those you've forgotten, go back and try to relearn them. Don't say I never taught you anything!

With MARGE in hand, you now have tools for efficient lifelong learning. MOTIVATE yourself by taking a walk around your town. ATTEND to your environs and create your own walking guided tour of historical/prominent sites. RELATE facts to sites using your smartphone for information or gather information from your walk (talk to store owners about the store's history!). When you return, GENERATE a story about your town, organize it around the path you walked, and tell someone about your adventures. EVALUATE your knowledge by reminding yourself of the information each time you are in town. Better yet, actually take someone on your guided tour! Learning is a whole-brain issue—it'll keep you active, should be fun, and is best when shared with others!

References

Dunlosky J., Rawson, K. A., Marsh, E. J., Nathan, M. J., Willingham, D. T. (2013). Improving students’ learning with effective learning techniques: Promising directions from cognitive and educational psychology. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 14, 4–58.

Pashler, H., Bain, P., Bottge, B., Graesser, A., Koedinger, K., McDaniel, M., & Metcalfe, J. (2007). Organizing Instruction and Study to Improve Student Learning (NCER 2007–2004). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Research, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

Shimamura, A. P. (2008). A neurocognitive approach to metacognitive monitoring and control. In J. Dunlosky & R. A. Bjork (Eds), Handbook of Metamemory and Memory (pp. 373-390). Psychology Press: New York.