Neuroscience

How to Not Take Things So Personally

Quick strategies for rerouting the messages that aren't meant for us.

Posted August 21, 2022 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- We are wired to take unpleasant comments by others personally, even though they say more about the other person than ourselves.

- We have choices to "consider the source" and use curiosity to imagine why someone is acting the way they are.

- Having compassion for others is a way of having compassion for ourselves. When we don't take things personally, we feel safer.

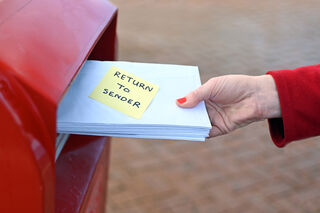

Don’t you wish there was a “return to sender” button inside your mind when someone is gruff (rude, frustrated, hurtful, thoughtless, accusatory... fill in the blank, please) with you when you just asked them how their day was, or ordered your Frappuccino from them, or even just walked past them in the street? With that proverbial “RTS” button fully operational, we could just send back the undesired comment with an, "Oh, here you go, wrong address; I think this belongs to you.” And even add a “have a beautiful day” just as a flourish. Instead, after these brushes with someone else’s “stuff,” it can take a little bit (or a lot) to shake off the feeling. We find ourselves walking away carrying what feels like a much heavier emotional load than what we walked in with—taking on the burden of someone else’s needs and issues, without our permission, rent-free, when caring for our own is daunting enough, thank you.

So complicated. So anguishing. So every day of our lives!

Even though intellectually we eventually, or even immediately, know that someone’s intentional or inadvertent boat rocking doesn’t belong to us, that doesn’t seem to do a darn bit of good for how our body reacts to the unpleasantness. We may find ourselves feeling unsettled, agitated, and having trouble focusing. We’re restless. Pacing. Pumped.

What just happened?

We want to reset and steady ourselves, but something deep within us just won’t let us let go.

There is good news, though: We can free ourselves from these moments.

“Free ourselves?” you may be thinking, “But what about that person taking ownership of their behavior?” Yes, absolutely, yes. Wherever and whenever possible. But in the meantime—since we are the ones who are suffering, project number one is helping ourselves feel better. And most fortunately this can be (if necessary) a DIY project: i.e., this is not contingent on the other person owning up to anything—though that would surely help. This is typically not a DIY project that we are naturally good (extricating ourselves from a sense of someone else’s negative behavior towards us) because of our primitive threat-oriented wiring, so please be patient and have grace with yourself—but read on, because despite our wiring, there are some definite workarounds we can do. Here are some ideas.

Change the Label to Neutral if You Can

Our survival as a species relies on the brain as a “good-enough” situation labeler. Not a perfect one. The amygdala, the threat detector/mobilizer part of the nervous system, and in any potentially threatening moment, grabs the label maker and goes for speed over accuracy and grabs the label maker eager to instantly warn us and instruct us to: “Fight, flee, freeze!” Our nervous system was built in a time of threats like tigers, not insults. Because of this, our first “labels” in situations of interpersonal unpleasantness may sound like this: “They don’t respect me! They are trying to hurt me! They hate me! They are trying to upset me!” Global statements about us personally leave us reeling. The degree to which we think those actions and words are personal about us is directly proportional to our suffering from them. Going back to decide on a second label is an essential step we often overlook. Second labels may sound like: “They are tired, they are frustrated, they are a child, they are feeling threatened themselves,” etc., etc., and leave us with likely a more accurate interpretation of the event, and gives our nervous system the bandwidth to reset.

Do a "Yes, and"

It’s understandable why certain actions upset us. That’s not under debate. However, we have choices about what we do with what people do to us or around us. At the same time, the more that we can realize that whether they meant it or not, it’s not good for us to keep revisiting that threat interpretation, the more choices we have about what to do next. Doing the “yes, and” maneuver is advisable here: “Yes, it was rude or hurtful, and it’s not going to be helpful to keep reviewing that. I’m going to keep working on compassionately pivoting elsewhere when this comes to mind."

Consider the Source

We all know the phrase "consider the source” and it is often said to dismiss or disparage, but a quote I learned in graduate school is meant to open up perspectives rather than bring down the blame:

“Everything said is said by someone,” was said by Humberto Maturana, a Chilean biologist whose work influenced the founding parents of family therapy.

This may sound obvious, but what is meant is that we need to consider the motives, history, experiences, biases, mood, etc. of the speaker, rather than on ourselves as the recipient or target of that statement: feel hurt (understandably) rather than where it came from.

Because communication is a two-way street, it will help if we were all more aware of the potential impact of our words on each other and do what I call “cleaning up as we go” when those words cause harm. Apologies are the first stop.

Why Should I Have Compassion for Them?

“OK so now it’s all on me? Why should I do this?” you may ask—as if it’s just for them that we do this thinking through. Perhaps nowhere is it clearer than in the words of The Dalai Lama who said that the first beneficiary of compassion is the self. We do this work to help our own hearts, first. If our world is populated with “enemies”—what does that do for us? Please be compassionate with yourself. This takes time. If someone “bumps” into you—even if it wasn’t on purpose—it hurts. So please take care of yourself.

Can we really be curious?

Why do people act gruffly when we are doing ordinary things? How is cheerfully ordering your coffee a trigger for someone? If we actually consider these questions in a not-judgey way but rather in a curious, I actually want to understand way, that is the beginning of helping ourselves not be so impacted by other’s behavior, stopping the threat reaction in its tracks, and maybe helping us to be more compassionate about what other people are going through. And being compassionate, instead of mad or hurt, helps us to feel better too.

The fact is that we don’t know why people do what they do, but when we stretch to imagine the reasons why our heart softens, we don’t feel attacked, we don’t have to fear them, and we can move on.

Clean Up As You Go

People are not trying to drive us crazy (mostly). It’s just who they are. It’s who “we” are—we can all do this to each other. And even if they are trying to do that—that’s about them, not us. When we imagine their communications as a package at your door, or in your mailbox, we can decide: Do we open it and sort through? It may feel like people’s behavior is kind of foisted upon us, but from another angle, it’s not. It’s an offering, not an obligation. And, let us not forget, your reaction to their package—is in turn a package for them—well, all in all, the more we understand each other, the better we do. Deciding to sort through and share your hurt feelings is meeting in the “aha middle”—it’s where you decide it’s safe to share why something hurt you—being willing to say that it wasn’t intentional.

Keep Only What Expands You and Helps You Grow

Maybe a “return to sender” button in difficult moments is something we can remember to push discretely within our own mind, so that we can settle ourselves, and a thoughtful, growthful conversation might ensue. Then we can respond to each other’s uncomfortable communications with curiosity, allowing for a deeper, more connected experience and understanding of life (this is on a good day, to be sure). Here’s to all of us having more of those.

Dr. C

©2022 Tamar Chansky, Ph.D.