Body Language

What Face Coverings Mean for Some Minorities

What is the most important non-verbal social cue in the United States today?

Posted January 28, 2021

This is a guest post written by Anna Piela, Ph.D.

Dr. Piela is the manager of the DICE Lab led by Professor Rogers in the Department of Psychology at Northwestern University. She is also a visiting scholar at the Department of Religion at Northwestern University. Her research focuses on the development of religious and gender identities among Muslim women in the U.S. and Europe.

The mass adoption of face masks has prompted an increase in deliberations on challenges to interpersonal communication, in particular non-verbal communication, in the public. Commentators observe that people may feel uneasy when they cannot read their interlocutors' facial cues, and that it is more difficult to convey empathy while wearing a mask. Eyes, as “windows to the soul,” are lauded as the body part that is best suited to convey moods and feelings in the era of the mask.

But for racial, ethnic, and religious minorities, facial expressions impeded by masks are the least of their worries. Masks don’t conceal some other very significant non-verbal social cues—most of all, race, and other markers of difference such as clothing.

White people do not have to fear for their life and safety because of their masks, unlike Black Americans who have experienced police and white supremacist violence before and during the pandemic, and for whom covering their faces aggravates the already high risk of police harassment. They do not have to be concerned that passers-by will accuse them of spreading disease because they are masked, which has been the experience of many Asian Americans who now resort to wearing sunglasses with their masks in order to conceal their facial features after Trump blamed the pandemic on the "Chinese virus." In New York, Hasidic Jews were also harassed and castigated. In Pennsylvania, Latinos were blamed.

Racialized violence against minorities who wear masks is also experienced by Muslim women who wear the Islamic face veil, also known as the niqab, in the West.

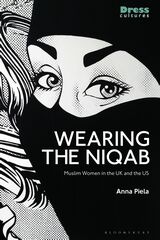

Trying to understand the reasons for voluntary face-covering among Muslim women, I have interviewed 19 niqab-wearing women in the United States and 21 in the UK (I share the findings in my forthcoming book, Wearing the Niqab: Muslim Women in the UK and the US). Sifting through the interview data to learn about communication experiences of niqabi women, I noticed that the respondents did not dwell much on interactive events such as smiles—instead, they focused on how they felt forced to carry out emotional labor in interactions in public to project a “non-threatening” demeanor. They felt it was prudent to start conversations and offer help.

A smile from behind a mask (or a niqab) can be recognized by others, but it’s a subtle signal—perhaps too subtle. The other person needs to really engage in order to notice a smile, and women who wear the niqab cannot always count on other people’s willingness to engage with them. They cannot afford going about their business without constantly risk-assessing and actively mitigating the risk of harassment. Many talked in their interviews about “making a special effort,” and “going the extra mile” in their interactions in public spaces. For example, Soraya from Scotland said that she was “extra chatty” and often complimented other women’s purses. Nabila from England told me that she often picked up food items off the floor at the grocery store in an effort to appear nonthreatening and helpful.

However, those challenges are apparently outweighed by the spiritual benefits of the niqab. All the women I have talked to talked about how the niqab helped them consolidate and strengthen their religious identities. The practice of face covering is not required by Islamic doctrine but, rather, a part of an individual and reflective process of constructing a pious subjectivity. For Sadiqa (25, African American), it is centered, in equal parts, on spiritual connection with God, modesty, and developing an ethical disposition [1] that is facilitated by having a material reminder symbolizing her aspirations.

For me, this [the niqab] is just one of the physical manifestations of me trying to get better, because it’s something I know, I can do better. You know, and I can persevere through this difficulty in hopes of getting better through another means. The reason I wanted to go into it, because I felt like you know, I know, I have so many faults of my own in different aspects. But, you know, there’s a saying that, like, a good deed is followed by good deed. So, you know, if like, the more good you do the more like a lead to doing more good, you know? So, in my head, I was thinking, OK, well, if I perfect, perfect this, maybe this will lead to me doing better in other ways. Cuz I’ll also, in a way, also a conscious reminder in my face, you know how to be and how to act and like, what kind of person I’m trying to aspire to be, even though I’m not that person yet.

Sadiqa’s narrative hints at the conscious and complex labor of shaping not just the present, but also the future ethical self. Perfecting a particular practice—wearing the niqab—makes way for a more encompassing approach to living out a pious existence to her satisfaction. For her, it is an intentional act of self-cultivation in which the body is an instrument utilized towards piety.

Socially, the odds are stacked against niqab wearers; they need to mitigate negative perceptions of Muslim covered women as oppressed, or alternatively, presenting a security threat. In the U.S., African American niqab-wearers have to negotiate a social reality whose logic dictates that they are vulnerable with or without the niqab. Therefore, although she regularly experienced simultaneous anti-Muslim and anti-Black prejudice, Sadiqa didn’t really consider taking the niqab off:

Even if we were to take off the niqab, we’re still Black. Like, we’re still, you know, African Americans, we still have dark skin complexion. So even if people weren’t judging us on this [the niqab], they could be judging us on our skin color … we’re going to get something from somewhere, you know. It’s already been something very ingrained in us, not just as Muslim but as African Americans.

Even though “we’re all niqabis now,” a commentator wrote, most people will be happy to leave the masks behind when the pandemic subsides. Muslim women who wear the niqab will continue to face intersecting inequalities and discrimination. And while non-verbal communication is currently often discussed in terms of facial expressions (and how masks obscure them), skin color functions as an important non-verbal cue that no mask can conceal. Given the racial politics in the United States, it is probably the most significant non-verbal cue of all.

Anna Piela tweets at @annapiela999. Her work is available via her website: www.annapiela.com.

References

[1] Mahmood, Saba. 2005. Politics of Piety. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.