Child Development

Why Does Anyone Need Therapy?

Unpicking the legacy of human evolution.

Posted October 12, 2020 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Humans are at the pinnacle of animal evolution. We’ve made it to the moon, can solve quadratic equations, compose sonatas, bake souffles, make cat videos.

And yet, in a given year, one in eight of us will receive treatment for mental health issues such as anxiety and mood disorders.

If we are so smart, why can’t we keep ourselves mentally healthy?

The usual answer is that we are poor at seeing our own feelings, thoughts, and behaviors objectively. And whilst this may be true, it still begs the question: Why?

In fact, the inherent difficulties of the human experience make sense when we understand a little about brain evolution and childhood development. Seen from this perspective, difficulties in our mental lives are likely at times.

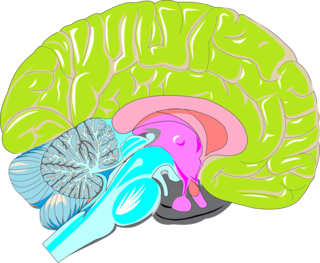

The human brain can be viewed as a three-part system or ‘triune brain’, made up of interacting structures that reflect our evolutionary history.

Our uniquely human powers depend on an evolutionarily recent outer part of our brain, the cerebral cortex. This part gives rise to capacities for conscious thought, verbal communication, planning, problem-solving, self-awareness, and so on.

We also share more primitive structures with other animals.

At the core is the ‘reptilian brain’, which is responsible for the body’s basic vital functions, such as breathing, heart rate, balance, or arousal. Wrapped around this is the limbic system, incorporating the hippocampus, amygdala, and hypothalamus, which first evolved in mammals. This is central to emotional learning and memory, and is designed to keep us safe; so is responsible for many of the value judgments we make, often unconsciously.

At birth, the ‘reptilian brain’ (that keeps us alive) is fully functional, the limbic system (emotional learning) is ready to learn from experience, and the cortical system (for explicit memory, complex thinking, or managing emotions) is initially inactive, but matures slowly over several decades. Whereas other animals have more rigid, pre-specified behavioral repertoires, humans' vast capacity for learning can equip us uniquely well for the world we find ourselves in.

However, this flexibility and capacity for learning mean we can get things wrong, too. What we learn in our specific childhoods—defined by their idiosyncratic experiences and caregivers, and by our personal interpretations and early understanding—may not serve us well as adults.

Harsh childhood conditions that do not nurture healthy development, can clearly shape our brains in ways that are maladaptive as adults. Extreme stress, neglect, a lack of attunement from caregivers, and our inherited tendencies can all play a part.

As a therapist, I often hear clients say, ‘I had a good childhood, I have no reason to feel the way I do.’ However, ‘good enough’ parenting can be elusive, as it involves appropriate challenge and support, and parents who are capable and willing to put feelings into words.

Furthermore, as what we learn depends on how we interpret what we see, our life experiences and other’s actions can take on a significance or meaning that was not intended. In particular, in the early years, we tend to assume that we are responsible for what happens to us, and learn accordingly.

Unsurprisingly, our learned childhood ‘life scripts’ may thus turn out to be self-defeating, or problematic in later life. At best, we enter the adult world with the skills to unlearn some of the mistaken and maladaptive beliefs we will almost certainly have acquired. If we have not acquired the requisite resilience skills, we will struggle to retain our mental health whilst we grapple with life’s ongoing learning and unlearning.

Our very human neocortical ability to imagine or expect things that might never happen—such as potential disasters, embarrassments, and humiliations—can lead to psychological trouble when paired with a primitive limbic defense system that cannot distinguish between real and imagined threats. Instead, defensive anxious, avoidant, and aggressive responses are launched automatically on the basis of unconscious childhood learning.

Thus we are set to continually reinforce old maladaptive patterns of behavior and potentially create stressful new problems too.

This is where therapy can help.

Good therapy brings unconscious drives to light and rebalances the power we give to the different beliefs, expectations, and goals that we acquired at different stages in our development.

Because limbic learning is largely reflexive, we usually have little conscious awareness of what is driving our adult behaviors. Notwithstanding, we tend to construct conscious adult (neocortical) narratives that explain or justify our behaviors, without realising the real reasons why we feel, think, and do what we do. Which is why we find it so hard to be objective about our motivations and feelings.

Have we evolved to need therapy? Not exactly. But the pairing of an imaginative and creative neocortex, together with a primitive, defensive limbic system, will always challenge us, given the complex demands of the modern world.

In Part 2 'How does psychotherapy change our brains?'’ I explore how (good) therapy can directly change and improve the functioning, regulation, and inter-connectedness of our critical neural systems. In part 3 (upcoming), I share some techniques and tools that we can use to help un-knot ourselves, without a therapist.

References

Cozolino, L. (2017) The Neuroscience of Psychotherapy: Healing the social brain. 3rd Edition. New York, U.S.A.: W.H. Norton & Company.