Free Will

Choice Blindness: Do You Notice If You Get What You Choose?

Choice blindness is widespread.

Posted August 14, 2023 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- People sometimes don’t notice that they get what they did not choose.

- Experiments indicate that our free will may in face be limited.

- We think our preferences affect our choices; often, however, our choices affect our preferences.

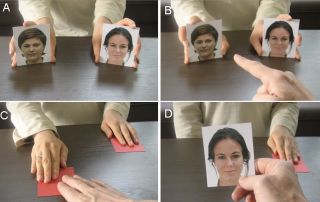

Imagine that you take part in the following experiment: An experimenter presents two black-and-white photos of young women and asks you to point at the one you find most attractive. You look at the pictures and point to the one you find most appealing.

The experimenter then places the photos face down on the table and slides the card you selected toward you. As you pick up the photo, you are now asked to explain why you chose the woman in the image.

Do you think you would notice if the photo you pick up is not the one you chose?

You're probably confident that you would. But it's most likely that you would not.

This experiment was conducted by cognitive scientists Petter Johansson and Lars Hall and their colleagues at Lund University. The pivotal point is that in certain instances, the card received by the subject is switched—utilizing a simple magic trick involving double cards—so that the picture to be justified is the one that was not initially chosen.

The astonishing outcome is that approximately 90 percent of the subjects failed to notice the substitution, even though the women in the pictures look very different. Moreover, subjects did not hesitate to justify why the woman depicted in the card they hold was most attractive, even if it was the other woman they originally chose. Scientists have termed this phenomenon “choice blindness."

A series of experiments by the same group has revealed that choice blindness occurs in various contexts: For example, it takes place in a supermarket when choosing between two jams that you are offered to taste. Despite significant differences between the jams, most customers still do not notice that the jam they taste a second time is the one they did not initially choose. Again, they happily explain why they chose that jam.

One of the most thought-provoking experiments pertains to how easily we can be swayed to change our political opinion. A few weeks before the 2010 parliamentary election in Sweden, a number of people were surveyed on the street about their intended party vote. They were then asked to fill in a form indicating their stance on 12 political issues of the day, using a “agree/do not agree” scale, such as tax rates and nuclear power.

Unbeknownst to the subjects, the experimenter secretly filled in another form, which was then swapped with the original one without the subject noticing. In this new form, some of the responses were changed on the scale to be on the other side of the party bloc boundary, compared to what the subject had originally responded. Subjects were then asked to give their reasons for marking the questions where the answers had been manipulated.

Very few discovered that any of the answers had been changed (92 percent accepted the manipulated form as their own). Surprisingly, for 48 percent of the subjects, their answers indicated a shift toward supporting the opposing party due to the manipulation, compared to what they had originally indicated. This figure is significantly higher than the 10 percent that political scientists and politicians usually think can be influenced before an election.

When the trick was revealed to the subjects, many admitted they were not as ideologically committed as they had thought. Conversely, many were relieved that they had not actually switched sides, saying, "Phew, I'm not a conservative after all!"

You think you choose what you prefer. But sometimes you prefer what you choose. To prove it, all you have to do is pull out photos of yourself from a decade ago. The hairstyle and clothing you wore at that time seemed like your personal choices. However, in hindsight, you realize how much you were influenced by the fashion trend of the time, and that the choices you made were heavily influenced by social norms.

It can be demonstrated that your choices also affect your preferences: In a follow-up to the photo selection experiment involving women, subjects were asked to choose between the same pair of faces at a later date. Remarkably, for those pairs where subjects were given the photo that they had originally not chosen, they now selected that photo significantly more often. In other words, the mere belief they had previously chosen the other woman made them choose her on the later occasion.

The experiments presented here pose major problems for those who assert that humans have completely free will. What we perceive as free choice is in many cases dictated by mechanisms of which we are unaware, and perhaps cannot even become aware of. Our perception of free will may largely be an illusion. It is even uncertain if a "self" governs our actions. In fact, the choice blindness experiments show that we rely more on what we see with our eyes than what we were thinking when we made the choice.

References

Johansson, P., Hall, L., Sikström, S. & Olsson, A. (2005): Failure to detect mismatches between intention and outcome in a simple decision task, Science 310, 116-119.

Hall, L., Johansson, P., Tärning, B., Sikström, S., & Deutgen, T. (2010). Magic at the marketplace: Choice blindness for the taste of jam and the smell of tea. Cognition, 117(1), 54-61.

Hall, L. Johansson, P. & Strandberg, T. (2012): Lifting the veil of morality: Choice blindness and attitude reversals on a self-transforming survey, PLoS One 7, e45457.

https://www.ted.com/talks/petter_johansson_do_you_really_know_why_you_do_what_you_do