Psychopharmacology

The Therapist Who Gets Me

The imperfection of perfection. Medication doesn't always help you.

Posted February 14, 2022 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Key points

- Here’s the deal with therapists: It can be hard to find one who fits.

- Medication is not a cure-all for depression.

- Transcranial magnetic stimulation can can depolarize neurons and evoke measurable effects.

When I graduated from high school, my parents asked me what I wanted. I answered, “A car and a shrink.” My father gave me his car, a honking huge Oldsmobile '98, and my mother gave me three names of psychotherapists. I chose the most radical of the names and began a lifesaving therapy that lasted for the next 15 years. “It was like your parents dumped me on my doorstep and said, ‘We don’t know what to do with her. You deal with it.’”

Someone finally recognized my moods for depression and sorted out my confusion of whether to major in voice, choreography, drama, English, or history. I started university as a drama major but couldn’t stand the people I was with and quickly switched to English, where I knew no one but saw my grades rise far above what I’d earned in high school. I was a loner but teachers liked me and I had a therapist who listened intelligently to my problems, my spells of depression when I failed classes, my loneliness. When my family faced the crisis of my oldest brother’s death, and my father threatened to throw me out of the family for daring to share a few home truths, my therapist was on the phone with me constantly. A year later, I had surgery to remove my gall bladder and a 36-pound ovarian cyst, he was again on the phone with me through the entire ordeal while I was in a third-world hospital in a Brooklyn ghetto.

We recently met up as friends when I sent him a link to a blog I thought he would be interested in. He was semi-retired, he told me. I think my entire body glinted. Except for one therapist in New York, my subsequent attempts at therapy had failed. My family wanted me to go back into therapy but I refused.

Here’s the deal with therapists: It can be hard to find one who fits. I needed someone who understood compulsive overeating, my family of three adopted kids, Catholicism, and my penchant for munching down books like they’re potato chips. Explaining all that felt like I was a psychology professor, constantly having to change subjects weekly. I needed someone who could keep up with me.

My original therapist could do that. He’d introduced me to poetry I hadn’t heard of, to the canon of books about the Vietnamese war both my brothers had fought in, he’d dismissed friends who hurt me by telling me their poop didn’t come out in Baggies either. When I moved away, we continued therapy in the summer and winter vacations until my crises passed and life in New York took hold and our contact dribbled away until the dawn on Facebook.

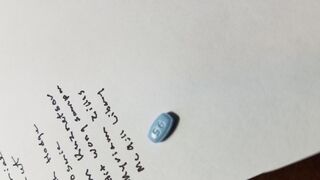

With the introduction of aripiprazole, I had a new horizon to confuse me: Who would I be without depression? I was doing things but when I was done, time hung heavily because I was no one I recognized. Therapy was advisable and in the course of a couple of emails, the perfect solution presented itself: Go back to the beginning, to the man who knew me best.

Our first session was shattering. I cried my way through it from a love I’d forgotten I had for the one person who, in my 65 years, had always had my back.

Addicts mature at a tenth or so of the usual rate of normies. When an addiction, like mine with food, takes hold at a very young age, the addict is stuck in time for what seems like forever. I don’t know how to set boundaries, how to deal with crazy bosses, how to budget, find work, go to the overly bright grocery store without slipping to the lip of a panic attack.

I need to be told what to say, how to find emotional and literal tools. In our first session, he gave me two pieces of stellar advice: It’s not what I will be without depression, it’s who I want to be. The other was that because I was too terrified to figure out how to use my Silver Sneaker privileges and my brother, who used his often, was in Maui for a month, I should relax and wait for Jim to come home and walk me through it. Swimming and water aerobics didn’t have to happen then, it could wait a month and I would be comfortable in crossing that threshold.

Still, I cried for three days. The realization that a kind of love had come back into my life, that unconditional support was possible, overwhelmed me. And me being me, I quickly felt I didn’t deserve it.

I reasoned with myself that aside from Pol Pot and Ted Bundy, every person deserves such riches. I told myself I was smart, witty, talented, and I have great hair: surely the right people would appreciate that and mirror it back to me. But it being January, with a lot of snow and friends I would have to fight for rather than take for granted, I couldn’t internalize what I told myself. And here was someone who had no problems with communicating without words his nostalgic love for me. He even came with a book list.

Our next appointment was three weeks out, plenty of time to struggle and then cave. Aripiprazole is not infallible.

I spent ten days in bed, weeping over the gift and wondering if, like an enticing box of chocolates, my therapist was too much for my constitution.

Then I ran out of aripiprazole. My pharmacy is in the too-bright grocery store that makes me feel naked and ashamed. It snowed a couple of inches and I didn’t have the energy to clear my windshields. I hadn’t bathed in God knows how long. The idea of getting through all that and the shakes I knew I’d have to go to and be in the pharmacy held me in thrall for days until one day I got up and showered right after having coffee. I was in a scramble to leave between eleven and one when the parking lot has slots open, and I could return close to my apartment. But where was my car key? I couldn’t find my driver’s license and debit card either. I had to stop for anxiety-driven diarrhea. I was a hot mess, and it was nine degrees outside when I got myself in second in line.

This is not, in itself, an important story but it became part of our next therapy session.

“It seems like you’re hypersensitive to light,” he said.

“I’m changing grocery stores for that reason.”

“I wonder if you would benefit from transcranial magnetic stimulation. I have patients who’ve benefitted from it a lot, including light sensitivity.”

“Transcranial what?” I asked.

“It’s pulses of stimulation to the brain. It can depolarize neurons, which helps with certain psychiatric disorders, including hypersensitivities. They’re studying it at Stanford and there are a number of practitioners in California. You should talk to your psychiatrist about it.”

“I will,” I said, wondering if it was available in Spokane or Seattle. Missoula isn’t exactly practicing medicine with chisels, but this was definitely a big city gig.

What was also notable about that second session was that I had to confess the effects of the first. He got it! He said that, despite pretty good parenting, it had not all been scones and clotted cream—my parents were not physically or emotionally there for me—and that on top of the effects of Catholic school, where guilt was taught alongside math and reading, and early onset of depression. I was, of course, overly grateful to him. And he said it was a pleasure to be considered the knight on a white horse.

Had he downplayed his role, I would have been disempowered because I sorely lack a sense of my own power. By taking it upon himself, he mirrored it back to me. I was in a telehealth session because I wanted to believe I was worth being on this earth, and wanting is the first step to personal power that overcomes a chaotic past.

We terminated the session with that old feeling of being understood and a new feeling of being able to talk about our relationship as part of the important experiences of my life.

I didn’t put on my pajamas until that night.