Anthropomorphism

The Danger of Dishonest Anthropomorphism in Chatbot Design

Human-like interactivity may seem clever, but it can lead to overtrusting.

Posted January 8, 2024 Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

Key points

- Anthropomorphic design can be useful, but unethical when it leads us to think the tool is something it's not.

- Chatbot design can exploit our "heuristic processing," inviting us to wrongly assign moral responsibility.

- Dishonest human-like features compound the problems of chatbot misinformation and discrimination.

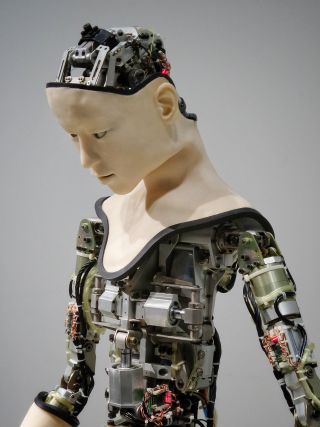

It is a universal tendency to assign or impute human emotional, cognitive, and behavioral qualities to nonhuman creatures and things. Owls are “wise.” Swollen rivers are “raging” and “angry.” Motorists customize headlights to look like eyes and give their vehicles names and genders. “We find human faces in the moon, armies in the clouds,” wrote philosopher David Hume in the 1750s, “and … if not corrected by experience and reflection, ascribe malice or good-will to everything that hurts or pleases us.” Our impulse to anthropomorphize continues with technology, from the language that we use (artificial intelligence) to the deliberate design of cuddly, personable companion robots. This impulse can have many benefits. But designing technology to “act” like a person or have human features can also be manipulative and exploitative.

Chatbots, and the large language models (LLMs) on which they are built, are showing us the dangers of dishonest anthropomorphism. Built with humanlike features that present themselves as having cognitive and emotional abilities that they do not actually possess, their design can dupe us into overtrusting them, overestimating their capabilities, and wrongly treating them with a degree of autonomy that can cause serious moral confusion. Chatbots programmed to express feelings or that provide responses as if typing in real-time raise significant questions about ethical anthropomorphism on the part of generative AI developers.

Motivations for Anthropomorphizing

We have two important motivations for assigning human qualities to nonhuman agents, technology theorists have suggested. One is our need to “experience competence” and to interact effectively with our environment. This type of anthropomorphizing helps us “understand” the world in our human terms. The other is to satisfy our need to forge social bonds, which, in the absence of other humans, can easily extend to forging human-like connection with nonhuman entities, such as companion robots for the elderly. These motivations are behind “anthropomorphism by design” (Salles et al., 2020).

However, dishonest anthropomorphism can occur when a technology is “humanized” with the aim of duping humans into interacting with it as if it is something it is not—it “leverages people’s intrinsic and deeply ingrained cognitive and perceptual weaknesses against them,” as Brenda Leong and Evan Selinger warn (2018). Generative AI tools feature a host of different anthropomorphic features. Some are explicitly designed to be human-like, such as character.ai, while others “seem” to be human as a byproduct of their design, such as Claude or ChatGPT. The point is that responsible design requires developers to think more deeply about why such features are built.

Seeing a Machine as a Communication Source

Through decades of research on human-computer interaction (HCI), we know that powerful psychological responses and assumptions largely govern our interactions with technology (e.g., Sundar et al., 2015). We tend to perceive machines or digital technologies as being more than simply a medium or channel of communication, but rather as a source of communication. This is an important distinction. Seeing a machine as a source leads us to interact with it socially. We treat technologies that have social characteristics in a social manner. We show politeness. We expect reciprocity. We make assumptions about its intelligence, its autonomy, even its capacity for creativity. In other words, we respond to a computer just as we would respond to another human as a source.

We don’t do this all the time, of course. A technology has to have three key elements to trigger this social response: it must be interactive, use natural language, and fill roles previously held by humans. Chatbots, of course, do a fabulous job of checking all three boxes. They arguably represent the pinnacle of this technological evolution. By design, chatbots invite us to treat them as a communication source. In other words, by design, chatbots are built to exploit our heuristic processing. The ethical questions raised by such design features should be clear. This is why, when chatbots are designed to respond to our prompts with expressions of emotion, we can object that such features abuse our tendency to engage in anthropomorphic reasoning and perception. It is also why Leong and Selinger include such features as part of their “Taxonomy of Dishonest Anthropomorphism”—even though their list predates the rollout of ChatGPT by several years.

A blatant example of what can be called dishonest anthropomorphism is how chatbot tools respond to our prompts in “human time.” In actuality, their responses to our prompts are measured in nano-seconds. They are instantaneous. But developers of several chatbots, including OpenAI’s ChatGPT and Anthropic’s Claude, have deliberately slowed down the responses so that they appear on the screen as if they are being typed and presented to us. OpenAI designers have explicitly decided to present the chatbot as more “human.”

Why would they do this? Because it triggers for us the “machine as source” heuristic, and we are likely to treat it as more “real” than it actually is. When you ask ChatGPT this very question, it responds that it is “a user-friendly feature designed to make interactions with ChatGPT feel more natural and satisfying.” It says, “When responses appear as if someone is typing, it creates the illusion of real-time interaction, making the conversation feel more dynamic and interactive. This helps users feel that they are having a genuine conversation.” Just consider that for a moment. It is a feature designed to exploit our heuristic processing to think that it is something it is not. It is a design feature to dupe us more effectively.

Another ethical concern here is the discrimination that can occur when the algorithmic settings of LLMs can be adjusted to “act like” a specific persona based on race, ethnicity, or other “traits”—when the LLM is literally anthropomorphized, in other words. A recent study showed how doing so resulted in the chatbot discriminating against various demographics, delivering significantly more “toxic” content when “set” to act like a certain group, such as Asian, nonbinary, or female (Deshpande et al., 2023).

Whether due to ignorance or a failure to care, developers and executives who anthropomorphize chatbots in ways that result in deception or depredation, or that lead users to treat them as something they are not, do a disservice to us all.

References

Deshpande, A., Murahari, V., Rajpurohit, T., Kalyan, A., & Narasimhan, K. (2023). Toxicity in ChatGPT: Analyzing persona-based language models. arXiv preprint: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2304.05335

Hume, D. (1757/1956). The Natural History of Religion. London: Adam & Charles Black, Section 3, para. 2.

Leong, B., & Selinger, E. (2018). Robot eyes wide shut: Understanding dishonest anthropomorphism. In Proceedings of ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability and Transparency, Atlanta.

Salles, A., Evers, K., & Farisco, M. (2020). Anthropomorphism in AI. AJOB Neuroscience 11 (2), 88–95.

Sundar, S.S., Jia, H., Waddell, T.F., & Huang, Y. (2015). Toward a theory of interactive media effects (TIME): Four models for explaining how interface features affect user psychology. In The Handbook of the Psychology of Communication Technology (S.S. Sundar, Ed.). Malden, MA: Wiley Blackwell, pp. 47–87.