Media

Ethics and "Synthetic Media"

Machine-learning digital "people" pose moral questions of harm and authenticity.

Posted September 17, 2019

Do you know who Hatsune Miku is? Have you seen Lil Miquela? And what about the crisp news delivery of Chinese anchor Xin Xiaomeng? If you’re unfamiliar with these names, that probably won’t last long. They’re at the vanguard of a type of media content that will inevitably grow more common. They’re appealing. They’re photogenic. They’re well-spoken. They each have audiences in the millions. And they’re not real humans.

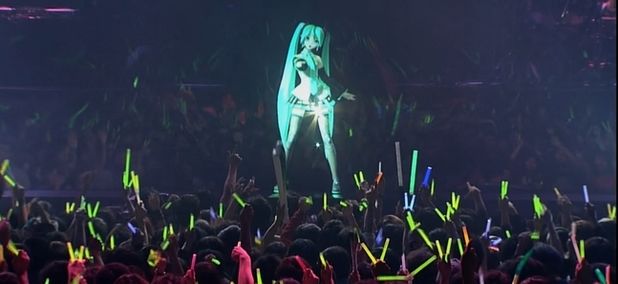

Synthetic media content is here. Different from “deep fakes,” these are “people” created by AI (artificial intelligence) algorithms that manipulate faces, speech patterns, tones, and other data to produce a human entity. These aren’t just mindless robots or holographic videotrons. Hatsune is a Japanese pop star whose music concerts are attended by tens of thousands of fans. Lil Miquela is a machine-learning chatbot with nearly 2 million followers on Instagram who regularly interacts with them as part of her own ongoing “story.” And millions of Chinese have gotten their news from Xiaomeng’s newscasts, produced by Xinhua.

Media consumers as well as media organizations – news outlets, social media platforms, marketers – need to start thinking seriously about synthetic media. With no agreed-upon standards for use or disclosure, what does responsible implementation of synthetic media look like? What possible types of harms and abuses should we anticipate? How might media professionals cultivate audience expectations and build trust? Is authenticity even likely to remain a value any more in this synthesized universe?

Quantitative futurist Amy Webb addressed these ethical questions in her annual “Trends” talk at the Online News Association conference in New Orleans. “These are people who are synthetic, who are built by AI systems to be responsive to us,” she told the ONA crowd of digital journalists, audience analysts, and platform developers. “What happens when they’re customized to us? When we start having experiences with them, and they’re learning from us?”

We are already seeing a shift in people’s assumptions and expectations, as Webb noted. We modulate our voices for different audiences and receivers all the time; it’s no great leap to do so digitally. We’ve gotten comfortable speeding up audiobook settings. In an unplanned experiment in China, millions of people interacted with Microsoft’s Xiaoice, a machine-learning social media chatbot. Only after a year were people told explicitly that she wasn’t real. The result? Most users shrugged.

Earlier this year, UK sports celebrity David Beckham was featured in a video for the nonprofit Malaria No More. In the minute-long segment, Beckham made a fundraising plea in nine different languages. His mouth movements and facial gestures were manipulated as if he were speaking with multiple voices – an arguably virtuous use of synthetic technology that cleverly amplified the global nature of the message.

The problem is, we can be easily duped. As we go through our day doing different tasks while also surfing online, we’re not (yet) conditioned to be skeptical of the authenticity of things. "It doesn’t occur to us to say, ‘Wait a minute, are these people both people?’” Webb said. “We’re not used to asking that question.”

With misinformation and fake news only likely to increase, the potential to harness synthetic “sources” for dark purposes should worry us all. But its pro-social possibilities, such as the Beckham clip, cannot be overlooked. The trick will be to envision, and then insist on, what one ethicist has called a set of “technomoral” values to shape this anything-goes environment before it starts degrading our lives. These values can help create a digital world that better allows everyone to flourish and make room for synthetic beings that can play important roles.

We need to start asking several questions. Not just of the “Is she real?” variety, but questions about what would be some guiding principles to help shape a digital environment that we would want to live in. What level of disclosure do we want to require of news outlets? Of marketers? We already have seen how much trouble we can cause by allowing key algorithms that shape digital behavior to remain hidden behind the scrim of corporate confidentiality; how much access should we be entitled to? What should a structure of accountability look like for bad actors? If we don’t think seriously about these kinds of questions, we invite the worst sort of technological determinism – we forfeit the chance to define the values that shape the technology, and instead allow technicist values of efficiency, convenience, and scale to shape our digital ethics.

Shannon Vallor’s “technomoral” virtues provide a useful framework through which to do so, emphasizing a neo-Aristotelian approach to the self and to digital community life. Vallor’s technomoral virtues that she considers crucial for human flourishing include honesty, self-control, humility, justice, courage, empathy, care, civility, flexibility, perspective, magnanimity, and wisdom. She wisely argues that these technomoral virtues should not be considered absolute, inherently universal or unmalleable. Rather, we should expect a certain level of flexibility that allows us to accommodate the continuously changing digital media landscape and our own psychological makeups. Like when we’re OK interacting with a synthetic person, when we’re not, and how we get to decide.

These values should guide us in building a kind of digital civic-mindedness that is inherently global and concerned with others’ wellbeing. This approach, she suggests, “allows us to expand traditional understanding of the ways in which our moral choices and obligations bind and connect us to one another, as the networks of relationships upon which we depend for our personal and collective flourishing continue to grow in scale and complexity.”

Our ethics should never be steamrolled by the coolness of new technologies. Vallor writes about “our growing technosocial blindness” that makes it “increasingly difficult to identify, seek, and secure the ultimate goal of ethics – a life worth choosing: a life lived well.”

Unless we insist that our values shape synthetic media and not the other way around, we risk becoming just as mindless as Lil Miquela.

References

Vallor, S. (2016). Technology and the virtues: A philosophical guide to a future worth living. New York: Oxford University Press.