Health

The Politics of Political Profiling

Profiling politicians has a long history and a controversial present.

Posted June 15, 2019

Attempts to understand the motives and actions of political figures have a long history. Sometime around the year 100 BCE, for example, the Greek historian Plutarch slipped a bit of psychological profiling into his biography of the Greek politician, Themistocles.

Themistocles was a Greek leader who, six centuries before he became Plutarch’s biographical subject, created the Athenian navy and saved Greece from conquest by the Persians at the Battle of Salamis. Themistocles’s mother was not an Athenian. She may not have even been Greek. She was therefore regarded as an “alien” in the eyes of Athenians.

Plutarch highlighted the significance of this fact in his subject’s life when he observed that Themistocles took steps to offset this disadvantage:

“Themistocles sought to induce certain well-born [Athenian] youths to go out to Cynosarges [a place frequented by “aliens”] and exercise with him; and by his success in this bit of cunning he is thought to have removed the distinction between aliens and legitimates.”

Plutarch also considered the behavior of the young Themistocles: “However lowly his birth, it is agreed on all hands that while yet a boy he was impetuous, by nature sagacious, and by election enterprising and prone to public life. In times of relaxation and leisure, when absolved from his lessons, he would not play nor indulge his ease, as the rest of the boys did, but would be found composing and rehearsing to himself mock speeches. These speeches would be in accusation or defense of some boy or other.” On other occasions, “he was taunted by men of reputed culture.”

By noting Themistocles’s mother’s status and his youthful actions, Plutarch implies that Themistocles’s considerable ambition may have been fueled by his desire to overcome his inherited alien status in Athenian society.

Some historians would undoubtedly question Plutarch’s psychohistorical dabbling. Historians depend on documentation, archeological evidence, and other tangible sources of information to draw conclusions. There are no historical records—diaries, letters, interviews, etc.—addressing Themistocles’s feelings about his mother’s outsider status in ancient Greece. And often there is no such reliable evidence to support analyses of more modern subjects of historical psychological profiling. Records providing reliable insight into the thought processes of historical figures are rare. Even diaries may mislead if the diarists slant their entries to present a flattering impression of themselves.

Furthermore, not everyone is convinced that modern psychological methods and insights can be accurately applied to past cultures and societies. Behavior is related to culture. Past cultures can differ significantly from modern culture.

The controversy increases even more when the subject of a profile is alive. More than 1,900 years after Plutarch wrote Lives, political profiling is still a popular pastime for amateurs and a focus of often heated debate for professional mental health care providers.

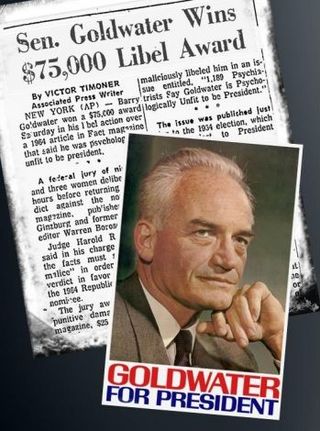

In 1964, 1,189 psychiatrists (out of 12,356) responded to a poll mailed to them by the publisher of Fact magazine asking them if they believed presidential candidate “Barry Goldwater is psychologically fit to serve as President of the United States?” Their responses embarrassed the profession. Goldwater was “diagnosed” with disorders like megalomania, paranoid personality disorder, narcissistic personality disorder, and schizophrenia.

Goldwater sued the publisher. He won one dollar for personal harm and $75,000 in damages.

A dozen years after the fiasco, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) issued guidelines known as "The Goldwater Rule," stating that is unethical for its members to give professional opinions about public figures whom they have not personally examined and from whom they have not received permission to forego doctor-patient confidentiality.

Interestingly, in 1976, the APA published the results of its task force called “The Psychiatrist As Psychohistorian.” The report reiterates the long-held APA position that condemns psychoanalyzing living persons, but it also “concludes that it is not necessarily unethical for a psychiatrist to produce confidential profiles of individuals in the service of national interest, and there are even occasions when such profiles may be appropriately published.”

In recent years, the Goldwater Rule has been cited frequently in reference to mental health care professionals expressing concern about the mental health of President Donald Trump. Traditionalists like the officials of the APA insist it is still unethical to psychoanalyze a living person without direct examination and approval. The APA claims this can result in inaccurate diagnoses and stigma directed at the subject and relatives. It could also be used as a political tool.

Advocates of openly discussing a president’s mental health insist they have a duty to warn if they, as professionals, see clear evidence based on their experience that he or she could pose a threat to others. If the leader of a nation with significant armed forces or nuclear weapons at his or her disposal were in any way subject to the instability characteristic of a mental illness or severe personality disorder, these professionals assert that they would be derelict if they remained silent.

If you combine the APA task force’s conclusion that it can be ethical to produce confidential profiles of living persons if it serves the national interest with the fact that the citizens of every country have the right to be reassured that their leaders are mentally healthy, then you are led to the conclusion that the field of psychiatry, and by extension all citizens, could benefit from a revision of the Goldwater Rule.

Presidents and presidential candidates routinely release the results of physical medical examinations. A leader’s mental health is, if anything, more important than a leader’s physical health; at least, it is for the health of the nation.

References

Plutarch. Plutarch's Lives. (1914). Translated by Bernadotte Perrin. Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press.

The American Psychiatric Association. (1976). The Psychiatrist as Psychohistorian. Washington D.C.: The American Psychiatric Association.