Empathy

The Long Battle of Cruelty and Empathy

How do we explain the terrible role cruelty plays in our lives?

Posted October 30, 2023 Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

Key points

- To be the target of cruelty is to be trapped in a world where innocence is betrayed.

- Aggression in humans is multifactorial, an adaptive survival mechanism with social and biological roots.

- Disruption in our wiring for empathy is not the primary cause of cruelty.

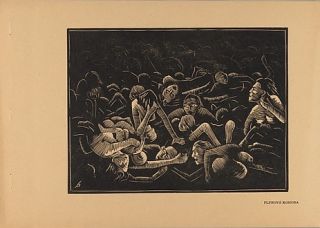

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg?itok=9dSsrUDE)

What is cruelty? To be the target of cruelty—whether by a troll on social media trying to intimidate you, by a friend or family member who strikes out in anger, or as a victim of political violence—is to be trapped in a world where innocence is betrayed.

In a world reeling from violent confrontations and the horrific behaviors they precipitate, it seems not only wise but also necessary to take a deep dive into the nature of cruelty. Acts of cruelty have been rationalized for the sake of family, tribe, religion, country, and empire since the beginning of humankind. Gruesome depictions of child abandonment, mutilation, starvation, and even murder fill our early folk and fairytales. Ancient legends and bible stories of pillage and revenge remind us of the brutality latent in our species. Aggression in humans is multifactorial, an adaptive survival mechanism with social and biological roots.

A favored definition of cruelty was put forth by psychologist Victor Nell in a 2006 article for Brain and Behavioral Sciences: “Cruelty is the deliberate infliction of physical or psychological pain on other living creatures, sometimes indifferently, but often with delight.”1 Nell hypothesized that cruel behavior evolved millions of years ago in early hominids out of predation, the killing and consumption of one living creature by another. Modern examples of cruelty are products of adaptations from our ancestors and have helped us establish social control as urban dwellers. In Nell’s view, the public spectacles of cruel punishments acted as deterrents to criminal behavior.

Cruelty, Nell maintains, exists only in humans and not nonhuman creatures. A cat “playing with” a live mouse cannot be said to be “enjoying” the suffering of that mouse. As far as we know, cats cannot imagine the consciousness of another creature, whereas some studies suggest the suffering of others pleasurably and sexually arouses humans engaged in the torture of other humans.2 Cruelty can have a psychologically rewarding effect.

How does empathy or the lack of empathy impact the capacity for cruelty? Empathy is the ability to feel what another is feeling. Do persons who commit acts of cruelty derive their “enjoyment” from their empathy with their victims? Or do they have damaged brain circuitry that limits or nullifies their capacity for empathy? If one definition of cruelty includes the positive or pleasurable feedback the perpetrator receives from harming another or in watching the other harmed, then that person clearly can feel what the recipient is feeling. That person does not have a damaged capacity for empathy, just a warped response to what they do feel. Contrary to popular belief, disruption in our wiring for empathy is not the primary cause of cruelty. Empathy, we often forget, is not necessarily bonded to compassion, defined by emotion researchers as “the feeling that arises in witnessing another's suffering and that motivates a subsequent desire to help.”3

Neuroimaging suggests that individuals who consistently exhibit violent aggressive behavior, including children who harm animals, show decreased activity in the pre-frontal cortex area of the brain responsible for executive functions like impulse control. Those who display reactive emotional and physical violence (someone hits you, you hit back) have a different neurological profile in brain scans than the small substrata of individuals with psychopathic personalities characterized by callous unemotional traits. Psychopaths do have damaged empathy circuits but account for only a fraction of the cruelty on the world stage.4

Is cruelty a learned behavior taught by a culture and reinforced by its societal norms? Would most of us commit acts of cruelty under dire, life-threatening circumstances? Cruelty erupts when individuals or societies are unable to contain their anger, frustration, and desperation. Feelings are contagious, and mass hysteria metabolizes ordinary citizens into frenzied action. Research psychologist Jeff Greenberg from the University of Arizona developed the Terror Management Theory (TMT) to explain this phenomenon. TMT posits that as hominids became aware of their own mortality, they adopted a cultural worldview in the form of a religion or a communal morality. When this worldview is threatened by another group, that’s when cruelty and violence emerge.5

We are all too familiar with the process of dehumanization, the assignment of nonhuman status to other humans. In his book, Less Than Human: Why We Demean, Enslave, and Exterminate Others, the philosopher David Livingstone Smith writes that acts of genocide can occur when the despised group is considered less than human. We can see so many examples of this: the dehumanizing institution of slavery in America, the methodical extermination of Jews and other so-called “undesirables” in Nazi Germany, the mass slaughter of the Tutsi ethnic minority during the Rwandan civil war, the Armenian genocide, or the massacre and displacement of Native peoples by white settlers in North America. Each of these demonstrates how one group has rationalized violence to justify the domination of another group and inflict culturally sanctioned violence for so-called moral or societal purposes, like honor killings and revenge. The labeling of marginalized and ostracized groups further dissociates them in the eyes of the dominant culture. Call a group of people “bloodsuckers,” “vampires,” and “parasites,” as Hitler labeled the Jews in Mein Kampf, and somehow ordinary citizens are able to accede to their mass extermination.

Are we as a species doomed to relive and recycle the violence and hurts of the past? Can we enlist the vast powers of our imagination to envision a new world? Sociologist Gareth Higgins recently said: “If you want a better world, tell a better story.”6 Can we learn to balance our biologically determined aggressive instincts with our capacity to love and care for each other and the earth? It’s worth encouraging.

References

1. Nell, Victor. “Cruelty’s rewards: The gratification of perpetrators and spectators,” Behavior and Brain Sciences, 09 August 2006

2. Longpre, N., Guay, J. P.’ Knight, R. A. “MTC Sadism Scale: toward dimensional assessment of severe sexual sadism,” Assessment (ASM) 26 (2019)

3. Goetz, J.L., Keitner, D., Simon-Thomas, E. “Compassion: An Evolutionary Analysis and Empirical Review” Psychology Bulletin May 2010

4. Viding, Essi, “Explaining the Lack of Empathy” from Psychopathy: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press (2019)

5. Greenberg, J., Arndt, J. “Terror Management Theory” in Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology, Volume 1, Sage Publications (2012)

6. Higgins, Gareth, “Revolution Stories” on Learning How to See with Brian McLaren podcast, October 20, 2023