Fear

The Fear of Abandonment: Missing Mothers and Fairy Tales

Here's how fairy tales capture dimensions of loss and transformation.

Posted March 31, 2023 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- One of the primal fears of childhood is abandonment.

- Folk and fairy tales explore how parental absence affects children and leads to growth and transformation.

- Support and belonging can be found in unexpected ways, as the heroes and heroines of folk and fairy tales often discover along the way.

One of my earliest and most frightening memories is the time I became separated from my mother in one of Last Century’s massive department stores. I must have let go of her hand, or she mine; which one of us wandered off, I will never know. I looked around, and suddenly, inexplicably, she was nowhere in sight. I felt pure terror. In the busy aisles, unfamiliar adults brushed passed me with cold, impassive faces.

Abandonment is one of our primal fears.

For nine months, we inhabit our mother’s body, completely dependent on her for life-giving essentials. When the umbilical cord is cut, we become separate beings, unmoored from our source. Unlike other primates, at birth, we are helpless and dependent.[1] Humans develop self-sufficiency at a slower pace than our primate cousins and remain immature longer than most. Without an attentive caregiver, our early existence is precarious.

Before Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis, speculated that separation from our mothers at birth is the central trauma of our lives[2], European philosophers, among them Søren Kierkegaard and Jean-Paul Sartre, theorized that fear of abandonment is a major component of modern consciousness. What they understood—the existential nature of our anguish, despair, and aloneness—we now embrace as a condition of our post-modern psyches.

Maternal mortality, dying while giving birth or thereafter, must have been high on women’s lists of ever-present dangers to their lives. Medical historians Van Lerberghe and Debrouwere estimate that maternal mortality could have been as high as 25 percent in prehistoric times.[3] In traditional societies, a solicitous maternal presence ensured safety, security, and survival. Her absence could be catastrophic, often presaging an arduous struggle for her offspring for food, shelter, and love.

Common wisdom often comes down to us through folk and fairy tales.

So it is unsurprising that the tragic event of a mother’s death or absence due to separation or illness found its way into them. These cautionary tales illustrated the challenges an orphaned child might encounter after such a grievous loss: loneliness, poverty, despondency, victimization by revenge, competition, jealousy, envy, and greed.

The tales don’t just depict these woes; some were maps to transformation from naïve and untested young girls to brave, self-sufficient young women. For heroes, the transformation required a warrior stance, slaying the enemy, or killing the monster. But for heroines, the prescription was the deployment of charm, wit, cunning, generosity, kindness, gratitude, and respect for nature. Remedial attributes and virtues, rather than sheer courage and brawn, secured her success over malevolent forces.

Many well-known tales begin with a mother’s death. Most often, though not exclusively, stories about mothers and daughters start in this manner. (“Cinderella” and “Snow White” are the best-known examples in the United States.) The death of the mother precipitates the daughter’s journey to find her way in a seemingly cruel world. Bereft of a tender, caring maternal presence, sorrow and woe besiege the grieving child, a trope much more common in stories about a daughter’s loss of her mother than a son’s.

In both cases, the abandoned child must “grow up”—that is, become her own true self—but the masculine-identified child is encouraged to take immediate action, while the feminine-Identified child is encouraged to suffer through the hardships. However, the tales also indicate that without the initial difficulty or abandonment, the heroine would not be required to discover her courage, self-respect, self-worth, and maturity.

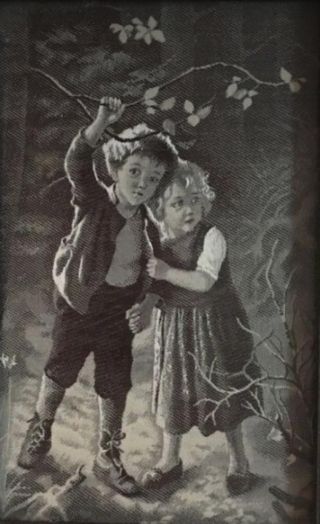

In some tales, the mother figure is not dead but metaphorically “missing.” She is emotionally neglectful, passive, narcissistic, or inadequately loving, like the mothers of Rapunzel, Hansel, and Gretel. Or she is beholden to her male counterpart. The consequences of having this type of mother are just as devastating as if she had died.

What do we make of all the wicked stepmothers? The frequency with which they appear indicates a truth about human wholeness. No person is all-good, all-giving, or all-knowing. No human is without anger, jealousy, greed, what Carl Jung called the repressed shadow, the split-off and unacceptable aspect of our psyches. In the tales, the negative qualities society rejects are projected onto the figures of the wicked stepmother, the witch, and the hag.

What mother hasn’t had moments of anger, frustration, exhaustion, and resentment and felt like a monster? What mother hasn’t wanted, against her best judgment, to lash out at a child? How shameful we feel accepting our emotionally-nuanced humanity!

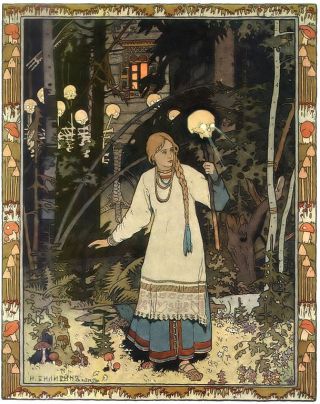

In fairy tales, the dead or missing birth mother is idealized and angelic. In “Cinderella,” the perfect mother is represented by a fairy godmother who appears when Cinderella’s need is urgent. Like all good fairy godmothers, she supplies the necessary goodies for Cinderella’s transformation. In the Russian tale “Vasilisa the Beautiful,” before Vasilisa’s mother dies, she gives her daughter a wooden doll, a stand-in for a fairy godmother, and a perfectly attuned maternal presence.

Both fairy godmother and magical doll represent the capacity of an abandoned child to internalize and elicit “the good mother” within. Despite early life disturbances, through facing adversity, the child develops the ability to trust her inner resources and intuition. Stories like “The Handless Maiden,” “Vasilisa The Beautiful,” and “The Miller’s Daughter,” in which the heroine must perform a series of impossible tasks, show the development of self to a greater degree. Help also comes from the natural world, from a frog that appears on the path, a wise bird, and a friendly wind, and here, too, the heroine must consult her inner wisdom in deciding where to put her trust.

Human wholeness admits we are complex creatures: generous and selfish, caring and disengaged. In fairy tales, as in dream work, we can interpret all the characters, including the non-human ones, as “parts” of our psyches. We are the needy, helpless children, and we are brave heroines and heroes. We are Beauty, and we are the Beast. We can be sturdy as a tree, blown about like a feather. We burrow in the mud of not-knowing, like frogs. We open our petals in the sunshine like fragrant roses. Every aspect of a tale can be interpreted and considered symbolically for a more expansive and revelatory understanding of our nature.

The fantasy ending of “happily ever after” can be re-visioned with the knowledge that our suffering does not preclude joy, transformation, possibility, and fulfillment. What the tales tell us is that we may be alone, but we are not forsaken; we are part of a vast universe in which helpful forces abound.

References

[1] Wong, Kate, “Why Humans Give Birth to Helpless Babies,” Scientific American, August 28, 2012

[2] Freud, Sigmund, The Interpretation of Dreams, “The act of birth is the first experience attended by anxiety, and is, thus, the source and model of the affect of anxiety.”

[3] Van Lerberghe, Wim & Debrouwere, Vincent. “Of Blind Alleys and Things That Have Worked: History’s Lessons on Reducing Maternal Mortality,” Research Gate, November 2000