Psychedelic-Assisted Therapy

How Magic Mushrooms Can Fix Depression

New research highlights the power of psilocybin to boost mood and offer hope.

Posted September 7, 2023 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Key points

- Many people who experience depression do not find relief through psychotherapy or existing medications.

- A new study found that psilocybin can be highly effective in relieving depression.

- The relative safety and efficacy of psilocybin suggest that it could be a powerful way to treat depression.

There is an urgent need for effective depression treatments for the 21 million adults in the US (8 percent) who experience depression each year; the numbers are even higher for females (over 10 percent) and people 18 to 25 years of age (over 18 percent). In addition to the suffering depression causes, it often leads to major life disruptions, such as missed work, strained relationships, and substance use disorders.

Well-established treatments for depression include psychotherapy and medications such as fluoxetine (Prozac). However, even the best-tested drugs and therapies help only about 60 percent of those who receive them. Additionally, many people on existing medication experience unwelcome side effects, such as headaches, emotional numbing, and the inability to reach orgasm, and the medications are often prescribed indefinitely.

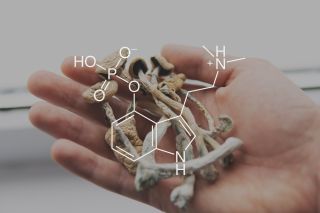

In this context, there has been a lot of enthusiasm for the potential role of psychedelics in treating depression. A recent study in JAMA, the top medical journal in the US, found that psilocybin (the active ingredient in so-called “magic mushrooms”) could provide rapid relief.

A large team of researchers across 11 sites in the US recruited 104 participants with mild to moderate depression. They excluded people with a history of psychosis or mania, more than a mild current substance use problem, and active suicidal intent. Those on medication for depression gradually tapered off the drug before the treatment phase of the study.

Participants were randomly assigned to receive either a synthetic form of psilocybin (51 people) or niacin, the control condition (53). The control allowed researchers to see whether psilocybin had an effect beyond the placebo response, which tends to be strong in depression treatment; niacin was chosen because the acute physiological response it causes (flushing) would make it harder for participants to know for sure which treatment they had received.

Trained facilitators guided all participants through a 7- to 10-hour session in which they received their dose of either niacin or psilocybin; both participants and facilitators were blind to treatment condition to isolate the actual treatment effect, versus the expectancies of those involved. The clinicians who evaluated participants’ depression symptoms and other variables were also blind to the treatment condition.

Does Psilocybin Work?

The psilocybin group had a much greater drop in depression symptoms than the control group, both at 8 days following treatment — 50% reduction in symptoms vs. 17% for the niacin group — and at 6-week follow-up: 54% vs. 19%. Interestingly, the vast majority of the improvement happened by Day 8.

Those who received psilocybin also reported a significantly larger improvement in their disability scores across the follow-up period — 61% vs. 25% — showing that the greater symptom relief led to more improvement in functioning.

A greater number of participants in the psilocybin group experienced treatment-related adverse events (82%) compared to the control group (44%). Most of these events were known effects of psilocybin; the most commonly reported were headache, nausea, and visual perceptual effects, which were mostly limited to the period when participants were experiencing the acute effects of the drug. No suicide attempts or self-injury occurred in either group. In contrast to typical medications for depression, psilocybin did not lead to emotional blunting.

How Does Psilocybin Work?

It’s remarkable that a single dose of a drug can produce such powerful effects on depression—especially among a group of people who had been depressed for just over a year, on average. Matt Zemon, an expert on the therapeutic use of psychedelics and editor of Psychedelics for Everyone, offers three likely explanations:

First, substances like psilocybin reduce activity in the default mode network of the brain, which Zemon describes as the brain’s “inner narrator that’s telling you you’re not good enough, you need to work harder, and you’re not loved.” As a result, it tames the negative thoughts that often run in the background during depression.

At the same time, psilocybin allows your brain to create new patterns of activity. Zemon compared brain activity in depression to skiing down a mountain over and over in the same tracks. Eventually “you can’t get to the other side of the run because of the deep ruts your skis have worn into the snow,” he explained. Psilocybin “puts a fresh coat of powder on the mountain, and allows neurons to fire that haven’t fired together maybe since you were a child.” As a result, “the brain is activated in a way that it’s not normally activated,” Zemon said. One of the most powerful changes may be greater hope, since depression so often is associated with hopelessness (Colloca and colleagues).

Finally, Zemon cites the powerful psychological effect of the subjective experience that psilocybin provokes. “In many cases there’s some type of feeling of a connection with a higher power,” he said, “or a type of interconnectedness of all things.” As a result, “the feelings of loneliness often subside,” and the person also experiences less shame, blame, and guilt about the past.

Taken together, these brain changes and subjective experiences “can allow people to heal in ways that traditional talk therapy and other existing pharmacological solutions” aren’t able to, according to Zemon.

Future Directions

It will be important for future studies to include a longer follow-up period to assess how long the effects of psilocybin last, though existing research that followed participants for a year found that the benefits were maintained. The JAMA study authors also note that future trials need to include greater diversity, as their sample was primarily White (89%), non-Hispanic (84%), and of relatively high socioeconomic status SES.

Although the FDA has not yet approved psilocybin for clinical use, these results add to a growing body of evidence showing that it could be a powerful new way to provide relief and hope to those who struggle with depression.

To find a therapist, visit the Psychology Today Therapy Directory.

References

Colloca, L., Nikayin, S., & Sanacora, G. (2023). The intricate interaction between expectations and therapeutic outcomes of psychedelic agents. JAMA Psychiatry.

Raison, C. L., Sanacora, G., Woolley, J., Heinzerling, K., Dunlop, B. W., Brown, R. T., ... & Griffiths, R. R. (2023). Single-dose psilocybin treatment for major depressive disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA.