Philosophy

A Fight Breaks Out in the Science of Consciousness

A recent letter called a leading theory of consciousness "pseudoscience."

Updated October 4, 2023 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Key points

- A letter claimed a leading theory of consciousness, Integrated Information Theory, was "pseudoscience."

- Many theories of consciousness face similar problems, so this attack seems unfair.

- There remain significant problems with terminology that add to the confusion.

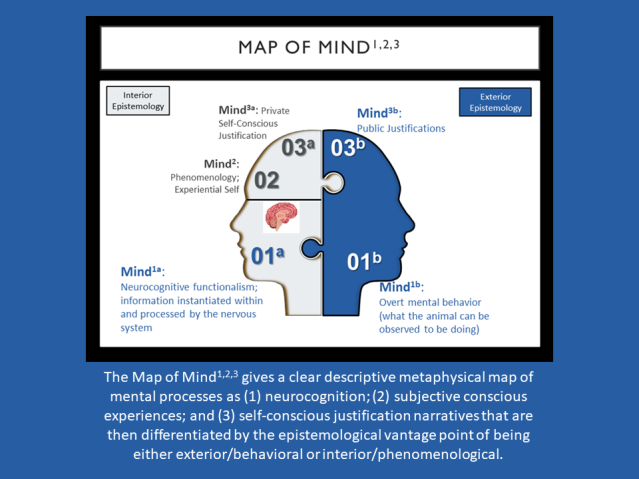

- There is a Map of Mind that might help make sense of the controversy.

Fight! Fight! Fight!

I remember hearing that in high school, and everyone would run toward the chant to see what was going down. Well, a major fight has broken out in the field known as the “science of consciousness.”

On September 16, 2023, an open letter signed by more than 100 scientists blasted Integrated Information Theory as “pseudoscience.” If you want to give a gut punch to any self-respecting scientist, you claim that they are doing pseudoscience. So now we have a fight on our hands.

To understand the nature of the fight, we can start with Integrated Information Theory (IIT). As I describe it in my 2022 book, A New Synthesis for Solving the Problem of Psychology: Addressing the Enlightenment Gap,1 IIT approaches consciousness by “highlighting the fundamental properties of experience and by framing how such properties might emerge in the material world. It also affords us a powerful mathematical formalization that yields a measure of integrated information, known as phi” (p. 375-376). In my review, I contrasted it with Global Neuronal Workspace Theory. I did so because these two theories are, arguably, the leading theories in the field of consciousness research. It is here that we start to encounter the reason for the letter.

You see, over the past several years, there has been an interesting project that set up a series of experiments that pitted IIT against GNWT. It was funded by the Templeton foundation to the tune of something like $20 million.

The series of experiments yielded some interesting results. The general conclusion was that both theories did reasonably well, and there were some findings that conflicted with both. But if one had to say that there was a winner, it probably was IIT. These findings were reported in news articles in both Science and Nature.

On the heels of this, some headlines emerged that claimed IIT was now the “leading” theory of consciousness and it was supported by empirical evidence. This is what the signatories were all upset about. They wanted to warn the public that IIT is not seen as a leading theory by many, and that, from their point of view, it has not been strongly supported by the empirical evidence.

They state it as follows in the open letter:

"The studies only tested some idiosyncratic predictions made by certain theorists which are not logically related to the core ideas of IIT… The findings therefore do not support the claims that the theory itself was actually meaningfully tested or that it holds a 'dominant,’ ‘well-established,’ or ‘leading’ status."

The letter goes on to state that IIT has many odd implications and suggests that things like plants or organoids created out of petri dishes or an “inactive grid of connected logic gates” might be conscious. It is from there that the letter states that the label “pseudoscience” should indeed be applied to IIT.

Before I comment on the letter, I will share my position on IIT. I find it interesting, but I am not on the IIT bandwagon. In my book, I claim that although IIT makes some important insights and advances the field, it still has serious problems. I argue that IIT “confuses the necessary structural conditions of consciousness for subjective conscious experience itself” (p. 377). This is a critique that cuts to the core of the claims IIT makes, so I am not pulling punches here.

That said, I am no fan of this letter. I am, however, a huge fan of the way Eric Hoel deconstructed the letter and rightfully called out all the signatories as “acting irresponsibly.” The reason is simple. The problems that IIT faces are very similar to the problems that are faced by virtually all the leading theories in consciousness research. Indeed, there are many critics of the field because there still are fundamentally knotty issues to be dealt with by all.

UTOK, the Unified Theory of Knowledge that I developed and outline in A New Synthesis, affords us an interesting angle to view this debate because it gives us clear ways to define science, behavior, mind, cognition, and consciousness. Through this coherent definitional system, we can see that the folks in the field of consciousness research do not have the same definition of consciousness. For example, some researchers define consciousness purely in terms of general structural and functional properties. IIT tends to be of this class. It provides a way to see consciousness as an integrated informational network that can learn from experience and move toward goal states. It attempts to quantify that via phi and place that on a continuum. This formulation means that you don’t need brains for something to be conscious.

For many researchers, however, any theory that even suggests that consciousness can exist outside of brains is a faulty theory. The vocabulary of UTOK allows us to see that, for these researchers, consciousness refers to the domain of Mind2. This concept arises from UTOK’s Map of Mind, depicted below.

Mind2 refers to the subjective conscious experience of being of animals with a brain. Mind2 arises out of Mind1, which refers to neurocognitive activity. Essentially, by definition, Mind2 cannot exist outside of a brain and the domain of Mind1. However, it does not follow that the broad concept of consciousness could not exist outside the brain. This is why we need to differentiate the concept of consciousness from the concept of Mind2.

Ultimately, UTOK helps us see that a key problem here pertains to definitions, concepts, and categories. My sense is that if everyone was familiar with the UTOK language system, much of this fight could have been avoided. Instead, now, as Hoel notes, the field is in serious danger of a major setback. In A New Synthesis, I summarized the current state of consciousness research in a way that helps us make sense of this fight and why it broke out and will close with it (pp. 385-386):

"Over the past three decades, scientists have developed a renewed interest in the concept of consciousness in both animals and humans. Global Workspace Theory, Integrated Information Theory, and others have captured the attention of many as affording new insights and leading to more advanced research paradigms. However, although much interesting work is being done in consciousness studies, there are still questions about how much genuine progress is being made.

"For example, Horgan’s book argued that a 'crisis' is emerging because there are many different “mind-body problems” that are all tangled together into a knotty mess, with no big picture viewpoint to sort out the issues and consolidate our understanding. Horgan believes the problems facing the field of consciousness studies are so significant that they will never be solved. From a UTOK perspective, Horgan’s skepticism is understandable.

"It seems likely that, unless a course correction is made, consciousness studies will inevitably become entangled with the long reach of the Enlightenment Gap. Indeed, the shadow of the Enlightenment Gap swallowed psychology and the philosophy of mind, and there is every reason to believe it will swallow consciousness studies unless there are advances in our metaphysical understanding of ontology that can bridge matter and mind and clarify scientific relative to subjective and social knowing."

References

1. Henriques, G. (2022). A new synthesis for solving the problem of psychology: Addressing the Enlightenment Gap. Palgrave MacMillan.