Behaviorism

Understanding Behavior via the ToK System

The blog clarifies the confusion surrounding the term behavior.

Posted April 11, 2015

Psychologists use the term behavior all the time and more than one current textbook defines psychology as the science of behavior. Yet there is enormous and ongoing confusion regarding what, exactly, is meant by the term behavior. I hope to make very clear why, according to the unified approach to psychology, it is nonsensical to define psychology as THE science of behavior, although, as we will see, psychology should be thought of as A science of behavior.

Let’s start by being clear about how the term behavior is usually used in everyday language. The common use (i.e., outside of science circles) of the term behavior is akin to conduct. Thus, a teacher might say, “The child’s behavior was unruly” or, to pull from recent headlines, we might wonder if a “policeman’s behavior was justified under the circumstances”. If you look behavior up in the dictionary, this is often the first definition.

Scientists, however, rarely mean this when they use the term. Instead, (behavioral) scientists usually mean observable actions of organisms (which is another common dictionary definition). Thus, a scientist might study the behavior of rats in a cage or children in the classroom. Although at first glance this seems pretty straightforward, serious study reveals that things are quite complicated, and different scientists mean different things when they use the term. At such, it is useful to review the history of the term and how it became a prominent part of the scientific lexicon.

The word behavior was rarely used prior to the 1900s. It emerged in the scientific lexicon largely through the work of John Watson. He first articulated “behaviorism” as a scientific approach that attempted to construe psychology (and the general study of animal/human beings) in a way that was directly antithetical to the “mentalistic” views of the dominant paradigms in psychology at the time, especially that of Wundt (i.e., Structuralism) and James (i.e., Functionalism), both of whom were explicitly concerned with human consciousness. One can see Watson’s position in the way he opens his 1913 behavioral “manifesto” in Psychological Review:

Psychology as the behaviorist views it is a purely objective experimental branch of natural science. Its theoretical goal is the prediction and control of behavior. Introspection forms no essential part of its methods, not is the scientific value of its data dependent upon the readiness with which they lend themselves to interpretation in terms of consciousness. The behaviorist in his efforts to get a unitary scheme of animal response, recognizes no dividing line between man and brute. The behavior of man, with all its refinement and complexity, forms only a part of the behaviorist’s total scheme of investigation.

What does Watson mean by behavior? Generally, he means the animals’ observable, functional activities and responses to stimuli. Although Watson’s Behaviorism dominated American academic psychology for several decades, it underwent a bit of a change with the rise of Skinner and his radical behaviorism. Skinner was not a stimulus-response psychologist like Watson, but instead thought of behavior in terms of its functional analysis. That is, whereas Watson often implied that behavior could be ultimately understood in terms of observable movements, Skinner was more focused on the function of behavior than the physical movement structure per se. He generally emphasized the behavior of the animal as a whole and focused experimentally on how it was shaped by “the function of the operant” (i.e., by consequences, especially reinforcement and punishment). Thus one could examine how pigeons could be shaped to play ping pong if one controlled their reinforcement histories.

Not only is behavior a bit more functional than structural for Skinner than Watson, but he also explicitly referenced consciousness. Although Skinner did not think it was helpful to think about consciousness causing behavior, he, much more so than Watson, acknowledged that consciousness existed. That is, clearly there was a phenomenological experience of being. Skinner characterized the experience of being (for example, a toothache) as an example of “covert behavior”. In so doing, Skinner’s behaviorism includes consciousness as a potential important consideration much more than Watson, although Skinner did strongly argue that consciousness should not be thought of as “causing” behavior, but rather was an effect or response that needed to be explained.

So, behaviorists generally thought about behavior as the activity of organisms. Early behaviorists tended to focus solely on actions that were observable by outside parties and were more movement/structural in their conception. Later, radical behaviorists shifted to conceptualizing behavior more in functional terms and, Skinner, at least, allowed for behaviors that existed inside the organism.

There were also neo-behavioral approaches, and these approaches are closest to the way modern psychologists think. Neo-behaviorists included folks like Edward Tolman, who argued that psychological scientists study behavior, defined as the overt actions of animals, but that in order to understand how it is that animals actually behave the way they do, we need to explain the action of animals via cognitive maps. Cognitive maps are hypothesized to be functional representations embedded in the nervous system that allow the animal to perceive and interact with its environment. Probably the most common conception of psychology today is the science of mind and behavior or of behavior and mental processes. In this sense, mind (or mental processes) would correspond to the information stored and processed by the nervous system, whereas behavior is the overt actions of the animal or person.

If this is beginning to make sense, hold on, because things are about to get complicated. According to the unified approach, the reason things get complicated is because psychologists (and biologists) have lacked an effective way to conceptualize behavior across different dimensions of complexity. Before we get into this, though, let’s ask the question as to whether modern scientists really are confused about behavior or not. Thankfully, the researchers Levitis, Lidicker, and Freund recently investigated this issue, both by exploring how various textbooks defined behavior (note they use the spelling behaviour) and listing different kinds of events and asking experts to characterize them. Their assessment was that there “no consensus” about what was meant by the term.

One of the things that make Levitis et al’s study interesting was that they asked for opinions about what constituted behavior. For example, they asked experts if the following is an example of behavior: (a) a person decides not to go to the movies if it is raining; (b) a beetle is swept away by the current in a river; (c) a spider spins a web; (d) a plant bends toward the sun; (e) geese fly in a V formation; (f) if a person’s heartbeat speeds up following a nightmare; (g) algae swim toward food; and (h) a rabbit’s fur grows over the summer season.

The researchers found much disagreement about these items. On the whole, though, there was some general agreement. For example, items a, c, e, and g were positively endorsed and whereas items b, d, f, and h were negatively endorsed, but there was not what would be considered strong consensus.

Levitis end their article with an interesting definition of behavior, which they define as “the internally coordinated responses of whole living organisms (individuals or groups) to internal or external stimuli, excluding responses more easily understood as developmental changes”. While this is a useful definition, I would want to point out that there emerges a problem with it from a psychological point of view. The problem is that this definition is essentially what Watson meant when he defined the term behavior. So, now we have behavioral biology essentially dealing with exactly the phenomena that traditionally defined behavioral psychologists.

The fact that there is a discipline of behavioural biology should give pause those who define psychology as THE science of behavior. This begins to highlight what is one of the most important points about behavior and why psychologists should stop thinking about their field as THE science of behavior. This point becomes clear when we see that there is usually a third definition of behavior in the dictionary. This definition has to do with actions, movements, reactions of natural (and nonliving) phenomena. It is perfectly natural to talk about the behavior of rocks or waves or cars. If you doubt me, google “how atoms behave” and you get 44 million hits--so it is pretty clear that physicists talk about the behavior of inanimate objects!

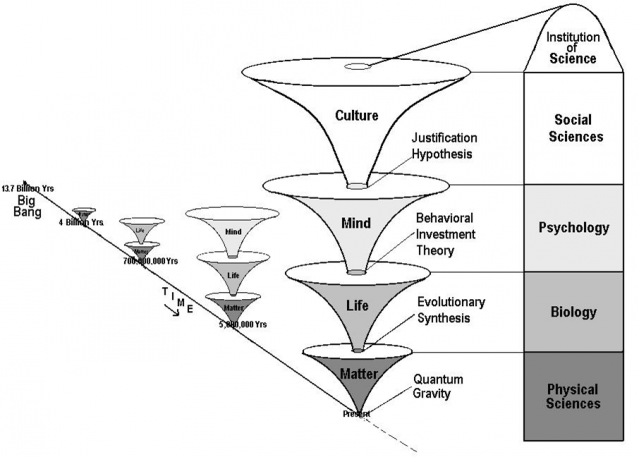

This brings me to one of the key points that I realized in constructing my unified approach and working with the framework of the Tree of Knowledge System. To get an effective conception of behavior we need to start from the bottom and work our way up. And the map afforded by the ToK helps understand how to do that. Indeed, you can think of the ToK as a map of different kinds of behavior and how they have emerged over time.

The Tree of Knowledge System

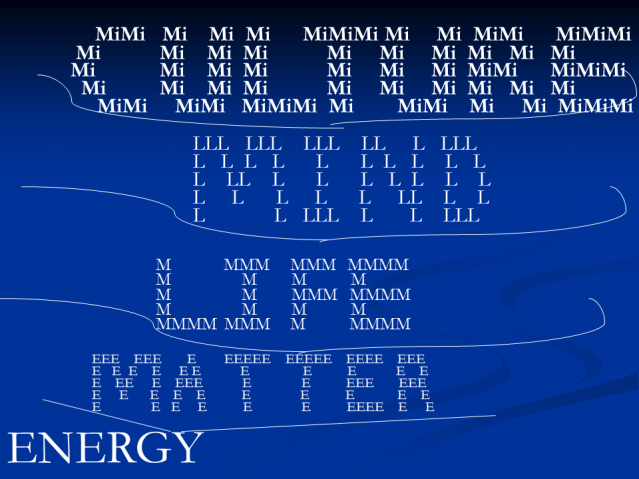

First, let’s understand why physicists can so readily talk about the behavior of atoms. The reason is that the most general conception of behavior can be defined as the change in object-field relationships over time. Indeed, I believe that behavior is the most basic metaphysical conception used by natural scientists. Metaphysics refers to the knowledge frames that are used to understand phenomena. Objects, fields, and change are the way natural scientists construe the world. Whether we are talking about Newton’s laws of action (AKA behavior) or modern formulations of quantum mechanics, the basic metaphysical ingredients involve objects, fields, and change. From this, I can be considered a universal behaviorist in the sense that I believe that everything is behavior, in the sense of being an unfolding wave of Energy-Information through time.

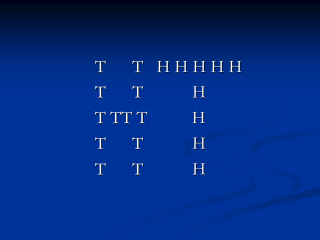

ToK System depicts this wave and shows that behavior occurs at different levels and dimensions of complexity. By a different level of complexity, I mean the level of analysis, which can usefully be divided up into the following: (1) parts; (2) whole objects; (3) groups of objects, or (4) entire ecosystems. The following slide offers you a glimpse into the relation between parts and wholes, showing that different levels of analysis can be thought of as different objects.

When Levitis et al emphasize that, for behavioral biologists, behavior refers to the “whole individual” they are making a “level of analysis” claim. A biochemist focuses on a different level of analysis (which would be a part relative to the whole organism). However, I would argue that biochemists also deal with behavior. What is the whole for the biochemist is a part for the behavioral biologist. For me, a what Levitis et al call behavioral biology could also go by the name holistic biology, in the sense that the defining feature is that the unit of analysis is the whole organism, rather than the behavior of its parts.

Many folks have pointed out that there are different levels of complexity in nature. However, the ToK System adds a crucial insight that there are also different dimensions of complexity in nature. The reason is that behavioral processes can be functionally organized by information processing. As such, different information processing systems give rise to qualitatively different behavioral patterns. The reason that cells and plants behave so differently than rocks and atoms is because the complexity of cells and plants is hierarchically organized by the genetic information stored in the DNA. Stated differently, if we were to “divide out” all the physical and chemical movement/action/behaviors, there would remain a bio-organic functional organization. Indeed, that is what the behavioral biologists are trying to capture. The behavior of the whole organism (or groups of organisms) is the clearest place to look for and see this functional organization.

What the ToK says is that there are four distinct dimensions of behavioral complexity because, following matter, there have emerged three systems of information processing, 1) genetic; 2) neuronal and 3) linguistic. The ToK System further labels the distinct dimensions of complexity in nature Matter, Life, Mind and Culture.

Life represents bio-organic functional patterns that cannot be reduced to physical and chemical actions/movements/behaviors. Thus, the behavior of algae moving toward a food source is a bio-organic behavior. However, as the level of analysis moves from biological wholes (like algae cells) to parts, the line and distinction between biology and chemistry and physics begins to blur.

Similarly, Mind on the ToK represents emergent functional patterns that arise out of neuro-information processing. This is empirically observable in examining how different animals behave relative to cells and plants. That is, just as cells and plants exhibit a dimension of behavioral complexity that is fundamentally different than inanimate material objects, animals exhibit a level of behavioral complexity that is fundamentally different than plants.

In my writings on the ToK and unified approach to psychology, I have advocated for clearly distinguishing psychological behaviors from biological and physical behaviors. I refer to these as mental behaviors. Mental is an adjective that characterizes the difference between animal behaviors and the behaviors of cells and plants (biological/organic), and rocks and atoms (physical/material). Mental behaviors are behaviors of whole animals (individuals or groups) that are mediated by neuro-information processing and produce a functional effect on the animal environment relationship. Consider the following slide. The actual falling of the cat is not mental behavior, but rather is physical behavior. But if the cat swivels in the air and lands on its feet, that would be characterized as mental behavior.

There are two broad “locations” of mental behaviors: (1) overt, in the form of third person observable actions and (2) covert in the form of cognitive processes, including experiential consciousness (which is observable in the first person). Thus, a spider building a web is an overt mental behavior and a rat pausing and making a decision at a choice point in a maze is a covert mental behavior. These are considered “third dimensional” behaviors on the ToK, and should be thought of as mental or psychological.

Human behaviors that involve or are regulated by linguistic information processing, what Skinner called verbal behaviors, exist on yet another dimension of behavioral complexity according to the ToK System. Cultural or socio-linguistic behaviors are separate because they are mediated by a separate information processing system.

With this analysis in place, we can go back to Watson’s behavioral manifesto and realize that there was a logical error embedded in his use of the term behavior and this has created a huge amount of confusion regarding the nature of behavior ever since. The problem is that he did not define behavior from both the bottom up and top down. Because he failed to appreciate that behavior exists at different dimensions of complexity, he introduced a concept that referred simultaneously to two mutually exclusive elements. It is surprising how long this term has lived without the proper recognition of this error.

One meaning of the term behavior that was embedded in Watson’s conception was the physical-material sense of observable, measurable movements. This is why Watson so clearly links the concept of behavior with the rest of the natural sciences in his opening paragraph. Yet, he also means behavior in terms of functional movement that cannot be reduced to physical movements. This variation in usage is problematic because it results in the term behavior being used in mutually exclusive ways. For example, sometimes the term is used to connect what psychologists study to what other “real” scientists study, as in “unlike those Freudian folks, we are a real science because we study and measure behavior.” Yet, sometimes the term is used in precisely the opposite manner. That is, the term is used to differentiate what psychologists study from what other scientists study, as in “psychology is the science of behavior,” which is supposedly different from what physicists study. Thus the same term, behavior, is used to justify connection with other sciences in some circumstances and used to justify differentiation from other sciences in other instances. If the same term can be used for two mutually exclusive purposes, there is a problem with it.

We showed here how, via the view of the universe afforded by the ToK System, we can take a bottom up view of the concept of behavior to get clear about these issues. The most general definition of behavior is change in object-field relationship, which is the most basic metaphysical conception in the natural sciences. This is important because it highlights that all sciences are sciences of behavior. Physics is the science of the behavior of objects in general. Particle physicists study the behavior of very small objects (e.g., subatomic particles) using quantum theory, and cosmologists study the behavior of very large objects (e.g., galaxies) using the theory of relativity. If physicists study the behavior of objects in general, then it logically follows that other scientists study the behavior of certain objects in particular. Chemists study the behavior of molecular objects; biologists study the behavior of living objects. This analysis highlights that there are obviously significant problems with defining psychology as “the science of behavior.” It isn’t the fact that animals behave that makes them unique--it is that they behave so differently from other objects.

This is why we need to concept of mental behavior to refer to the behavior of animals as a whole. And whereas behavioral biology might examine unicellular organisms and plants, the behavior of the animal as a whole should be recognized as a psychological or mental behavior, rather than biological or organic behavior. And human mental behavior, including as it does the verbal dimension of behavior of which this blog is an example, is still another kind of behavioral organization, existing at the socio-linguistic/Cultural dimension of complexity. This is why we should refer to human psychology as a different branch of psychology, and why, contra Watson, there is indeed a behavioral dividing line between man and brute.