Bias

Bias in the Competition for Scarce Kidneys

There is a bias in our criteria for a replacement kidney.

Posted November 8, 2021 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Key points

- There is bias in the selection of kidney transplant recipients, despite good intentions.

- Old people and mentally-impaired children are less likely to get a new kidney.

- The survival of the organ is actually preferred over the survival of human candidates.

- Random selection (not good intentions) may be the best way to avoid bias in our selection criteria.

Shirley was 67 years old. She was diagnosed with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and was excited when her name was added to the waiting list for a new kidney. Piper was 33. She too had ESRD, and she too was added to the list. But 88,000 people were already on the list, and only 18,000 kidneys were available. The average life expectancy for folks on dialysis is (at best) 5 years.

Piper received a kidney when she was 34 and lived 10 more years. Shirley died just before her 68th birthday from complications that are typical of long-term hemodialysis.

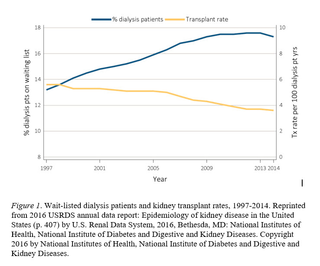

The names I used are fictitious, but the situation is real. It happens around 261 times a day, every day of every year. Why? We can delay death but there is no cure. The chances go down each day a candidate waits for a new kidney. But there aren’t enough donor kidneys to go around. Someone has to decide who must wait too long for it to matter. That decision is too hard for a human—so we rely on criteria. But won’t there still be bias in our criteria?

Are Some Groups Neglected by Assessment?

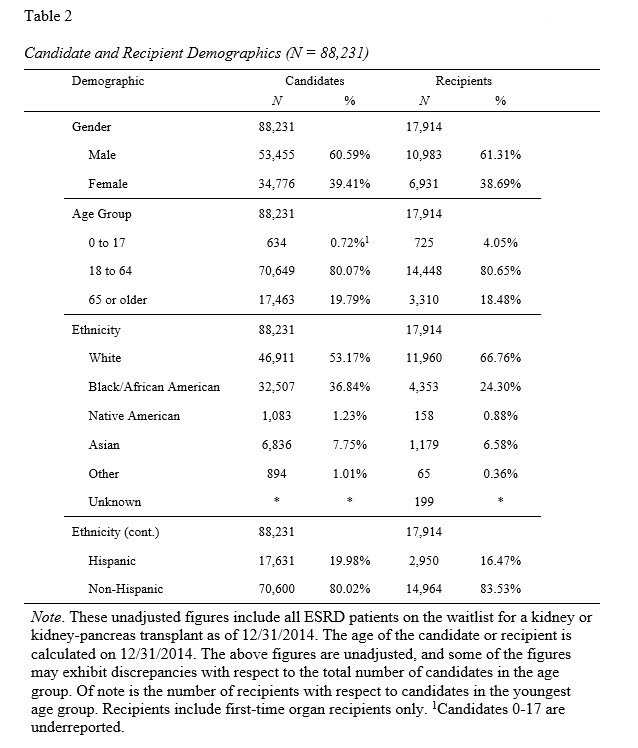

The possibility of inadvertent bias in our criteria was the basis of my dissertation. I learned all I could about the dreaded waiting list. Eventually, I figured that if I compared wait times for a replacement kidney, I could see which people waited too long, and which people got one right away. Were there certain groups that waited longer than others?

When I conducted my research in 2017, the official number of candidates on the replacement kidney waiting list was about 88,000. Only 18,000 received a transplant per year. Those aren’t very good odds. The odds get worse when you consider that 678,000 people needed one but didn’t even make the list. In fact, more people die of kidney failure every year (about 95,000) than are on the waiting list for a new kidney (Meinecke, 2017). How do we decide? Is it fair?

I Used the Goldilocks Approach…

To compare folks on the official waiting list for a new kidney, I needed to sort them into groups. I could have used race (because most recipients are White). I could have used gender (because most recipients are male). But I decided to use a Goldilocks approach.

- Are they too Young, Too Old, or Just Right (physically fit)?

- Are they Too Slow, Somewhat Slow, or Just Right (mentally fit)?

I figured that the Just Right group would get most of the kidneys. Remember Goldilocks and the Three Bears? My dissertation design was kind of like that. I sorted my data into “too this,” “too that,” and “just right.” Like hungry little girls looking for porridge, we’re kind of picky even when something is free.

I Stumbled on a Paradox

My review of the literature indicated that most who died from ESRD that year had waited the longest for a transplant. This fit a theoretical framework called the Stereotype Content Model by Dr. Susan Fiske of Princeton (i.e. prejudice based on lack of value to society; Fiske, 2011). So I conducted a causal-comparative study to see if the longer wait times of kidney candidates would bunch together (e.g. too old or too mentally challenged to handle a transplant). Sure enough, the results of one-way ANOVA indicated that children had significantly lower wait times (see Footnote 1). In contrast, retired people had the longest wait times, despite having contributed a lifetime of labor to society (see Footnote 2). Don’t old people have the same right to life as young people?

Deeper analysis revealed that, all things considered, those who are more mentally fit will be more likely to receive a transplant, no matter how young or old they are (see Footnote 3). Why? It’s because taking care of an organ is really complicated—in theory, only the more intelligent candidates can be trusted to take good care of their gift. But don’t mentally impaired children with their whole lives ahead of them deserve the same chance (Long, 2015)?

And now for the kicker. The primary criterion is the survival of the donor organ. Not the survival of all those people (Naesens et al., 2014). So that is what I discovered—an ethical paradox. The need to ethically allocate scarce organs has resulted in criteria that favor the survival of human kidneys over the human candidates who need them (Meinecke, 2017).

Can We Provide Justice for All?

When I started out on my dissertation, I never dreamed I would work with the U.S. Renal Data System (USRDS) or receive permission from the director of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). But I did! I want to mention here, they were incredibly kind to me. They made my study possible—just when I had designed myself into a corner. Thank you! Yes, Virginia, the quality of mercy is not strained.

I never dreamed the evidence would be so scary, and yet something about it all comforts me. Maybe it isn’t bias after all. Consider this:

- Those who get a new kidney often feel guilty for surviving.

- Those who don’t get a kidney often feel angry at an unjust world.

- Those who try so hard to ethically decide are accused of bias anyway.

Maybe we are blaming one another for a bias in our selection criteria when there was no hope of fairness? There are many ways to choose, but all of them are fraught with irony (Meinecke, 2017). Only a random outcome helps us stop blaming one another. My committee encouraged me to trust in my findings and simply report what I had found.

At such times as these, we wonder whether something far greater than our criteria has always been there to make these hard decisions about life and death. How can our criteria be just if the best we can hope for is to save a mere 2.6 percent of this desperate population? The very hope of deciding such a thing seems beyond the scope of the principle we call justice (Smith, 2006).

Beyond such a principle is another idea we call mercy—which is often more fickle than it is fair.

References

Fiske, S. T. (2011). Envy up, scorn down: How status divides us. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Long, S. (2015). Squashed dreams and rare breeds: Ableism and the arbiters of life and death. Disability & Society, 30(7), 1118-1122. doi:10.1080/09687599.2015.1070544

Meinecke, L. D. (2017). Neglected by assessment: Industry versus inferiority in the competition for scarce kidneys. (Doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. (ProQuest No. 10689852)

Naesens, M., Kuypers, D. R., De Vusser, K., Evenepoel, P., Claes, K., Bammens, B., . . . & Jochmans, I. (2014). The histology of kidney transplant failure: A long-term follow-up study. Transplantation, 98(4), 427-435. doi:10.1097/TP.0000000000000183

Smith, M. D. (2006). Major issues in ethics of aging research. In Handbook of Models for Human Aging (pp. 69-77). Academic Press.