Education

On Gap Years and Privilege

Don't dismiss gap years because they're associated with privilege.

Posted May 23, 2016

Gap years are often a sign of privilege. It’s true.

Media coverage of Malia Obama’s decision to take a gap year before college has brought a new level of attention and scrutiny to gap years in the US. Among the many opinions in the media, there are those who dismiss gap years because they are associated with privilege. Some even use this association as an opportunity to share assumptions that one has to be rich to take a gap year and that they are glorified vacations of little value.

But, the story about gap years and privilege is complicated, and dismissing them because of who they are associated with is a mistake. To do so would be to abandon a critical opportunity for learning and growth that all students need, including those who are traditionally underrepresented in higher education. If you’re concerned with equity and educational access, give the gap year a closer look.

Privilege and Access to Gap Years

Looking at the data about gap year participants in the US, it’s easy to see that gap years are associated with privilege. Research from The American Gap Association, a non-profit trade association, illustrates this clearly. Their published data shows 61% of gap year participants who reported their family income in a recent survey come from families with an annual household income above $100,000. The same survey shows 84% of gap year students are White.

One could look at this data and assume two things: 1) lower and middle income students are excluded because gap years are expensive; 2) gap years are designed to appeal to White students. A quick look at the websites of gap year program providers in the US might support these conclusions; many feature programs ranging from $8,000 — $16,000 per semester and pictures are dominated by White participants.

But, privilege is not necessarily inherent in gap years. Research we conducted at Thinking Beyond Borders demonstrates that the lack of diversity in gap years is more complicated than it may appear. Program providers throughout the industry are making significant efforts to expand access to gap years. Americorps and City Year are two of the largest gap year providers in the US. They charge no program fees, pay participants living stipends, and provide education awards for college tuition. Other program providers go to great lengths to provide scholarships and recruit students from traditionally underrepresented communities. Global Citizen Year is a leader in this regard, providing scholarships to the majority of their students and recruiting an impressively diverse student body. Other non-profit and for-profit providers including Rustic Pathways, Carpe Mundi, and Where There Be Dragons offer need-based scholarships to help provide access to their gap year programs.

At Thinking Beyond Borders, we have made extensive efforts over the years to diversify our student body by providing scholarships. As a relatively small non-profit, we’ve succeeded in providing 25% of our students with scholarships. While we’ve made efforts to identify funding to expand our scholarship offerings, we’ve encountered significant hurdles with traditional funders. Most government and foundation grant guidelines for educational funding specify that grantees offer accredited K-12 or higher education programming. Additionally, high quality gap year programming requires a significant investment in each student. Funders often seek grantees who touch as many lives as possible, rather than making a big investment in a few. We are proud that our scholarship funds at TBB have been generously contributed almost exclusively by our alumni community — families who are intimately aware of the value we create in students’ lives. But, we have found pursuing other funding sources to be unproductive.

While these efforts are helping to address the issue of program cost (and there is a long way to go here), there is another major hurdle to diversifying gap years. Lower and middle income students are often discouraged from taking gap years by their families, educators, and community leaders. For good reason, these influencers in the lives of students heavily emphasize the importance of going to college and not letting anything stand in the way. Winson Law, a first-generation college student and gap year alum, interviewed over a dozen college access and success educators who work with underrepresented students. He found a deep divide among these educators with regard to gap years. About half supported the concept, saying that intentionally designed programming to help students find purpose and direction would likely result in higher college graduation rates. The other half rejected gap years, most commonly citing experience and research showing that delaying college matriculation increases the likelihood that students won’t graduate from college.

This latter fear is common, including parents and educators in privileged communities. While this seems quite damning for gap years, it’s important to note that the research supporting this conclusion does not distinguish between a delay and a gap year. Nina Hoe’s dissertation notes that represented in these numbers are both those who took intentionally designed gap years and those who delayed due to family, financial, or personal concerns. Lower and middle income students face significant challenges that higher income students do not with regard to accessing and succeeding in college. With factors including the need to contribute to their families’ income, lack of examples and expertise in navigating the college process, and facing campus communities where they find themselves as isolated minorities, the challenges these students face make their path to college graduation categorically different from more privileged students. And, because delays in matriculation for these students are often associated with these challenges, the impact of such delays on their college graduation is wholly different from the impact an intentionally designed gap year program would have on any student.

It’s important to recognize that gap year providers have significant work to do in their own programs and operations with regard to diversity and inclusion, as well. Like other institutions in education and US society, the leadership and staff of gap year organizations often does not reflect the diversity of graduating high school seniors around the US. Programs and student support — from the structure of mentoring relationships to the content of packing lists — often reflect the needs of higher income, White students. These factors, along with others, can result in underrepresented students and families seeing gap years as a space that is neither designed for nor accommodating to them. Even worse, they can result in underrepresented students who take gap years feeling underserved and isolated while in the midst of an already challenging learning experience. We absolutely have more work to do in this respect at Thinking Beyond Borders, and we see this as an important area for growth for the industry of which we are a part.

The Value of a Gap Year

To understand the value of a gap year, we first have to define what it is. Generally, educators agree that a gap year is an intentional transition between high school and college that results in meaningful learning and growth. While taking time away from school to earn funds for college tuition is incredibly important for many students, this is often not considered a gap year because it lacks intentional educational design and outcomes.

There are three key factors that make up an intentionally designed gap year that results in meaningful learning and growth:

- Authentic engagement with interests — This can be accomplished by working, interning, or volunteering in a manner that exposes students to experts and provides enough experience to illustrate the nuance and complexity of interests. (Note that there is important critique of the issues of privilege involved with the volunteering often associated with gap years — that has been brilliantly addressed by Eric Hartman here.)

- Committed mentorship — This should be an adult who is invested in meeting regularly with the student to support personal reflection and growth. The mentor should also be old enough to provide perspective on the student’s current developmental moment and the stages to come.

- Learning support — This can be an educator, group of peers, and/or planned curriculum that helps the student process their experiences through inquiry and support in connecting their learning about the world with their personal growth and understanding.

Note that none of the factors above require students to travel internationally or even participate in a gap year program. Students can create gap years that incorporate all of these factors with careful planning. But, the rise of gap year programs in recent years is due in part to the fact that they can build an intentional program that incorporates these factors.

While there isn’t a lot of great statistical research yet on gap year outcomes, there is some important data to consider:

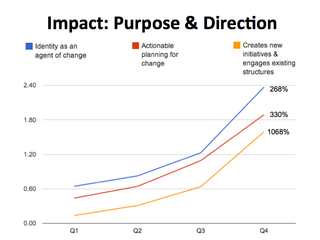

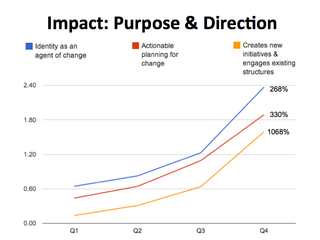

-

Source: Thinking Beyond Borders, used with permission

Source: Thinking Beyond Borders, used with permissionBob Clagett, whose career in college admissions includes decades of leadership at both the high school and collegiate level, conducted an excellent study showing that students who took gap years at Middlebury and UNC Chapel Hill achieved higher GPAs in college than they would have without a gap year.

- At Thinking Beyond Borders, we conducted research that showed our gap year students develop a dramatically improved sense of purpose and direction for their studies and careers, among other important outcomes.

- Nina Hoe’s dissertation examines the effects of intentional gap years for different demographics of students, demonstrating that students from all backgrounds benefit significantly.

- The American Gap Association published the results of a large sample of gap year alumni that provides a rough snapshot of the demographics and behaviors correlated with those who took gap years.

This data reinforces what college admissions directors and educators have seen for years — students who take gap years are better prepared to take advantage of the educational opportunities college has to offer. If the data hasn’t convinced you, consider that educators and institutions with extensive insight into how gap years affect students have endorsed and invested in the idea. William Fitzsimmons, Dean of Admissions at Harvard University, has long been a vocal advocate. More recently, institutions including Princeton, Tufts, UNC Chapel Hill, and Florida State University have all invested funding to help more students take gap years.

Who Benefits from Gap Years?

Perhaps the most obvious beneficiaries of gap years are the students and their families. The research cited above shows that the purpose and direction they gain from their gap year will pay great dividends when they get to college. Most specifically, they’re likely to perform better in classes and may even graduate earlier (American Gap Association’s research showed median time to graduation for gap year participants was 3.75 years). Given the cost of college tuition, this suggests that students and families are likely to receive a stronger return on their higher education investments if there is a gap year first.

The data doesn’t show another outcome that years of talking to students before and after their gap years reveals. Ask many high school seniors to define the purpose of high school, and they’ll tell you it was to get grades and test scores to get into college. It is rare to find a student who will describe a personal passion that has driven their work in high school. They took the classes assigned, chose the electives that would look best on their transcripts (sometimes disregarding their own interests), and got the best grades they could. Most high schools do not teach students to meld their passions and curiosity with their learning.

Yet, higher education requires students to bring their own sense of purpose to their studies. Colleges and universities offer a mountain of curricular, co-curricular, and extracurricular learning opportunities. To take advantage of these resources, students in most majors must chart a course of learning that results in meaningful learning and relevant expertise. This is where the purpose and direction gap years provide shines brightest. Yes, gap year students earn higher GPAs in college. But, perhaps more importantly, the stories I hear daily from gap year alumni students is that they have taken ownership of their learning in college both inside and outside of the classroom. They tell of their excitement not just in class but in connecting further with their professors during office hours to dive deeper into the subject. They seek recommendations for study abroad programs and internships that will satisfy their desire for knowledge and experience rather than just pad their resumes. Most importantly, they are pulling each of these opportunities together under their passion to become experts in issues that matter to them and to the world. Sure, higher GPAs are great, but it is stories like this that lead parents to send us thank you notes years after their students’ gap years.

Finally, developing this sense of purpose and direction intentionally through experience and reflection may have long term implications for students’ happiness. By both learning the skills to identify true passions and align one’s talents with them, students will be better prepared to find meaning, joy, and fulfillment in their college and professional careers. Winson Law eloquently points out that lower income and immigrant students like himself are more likely to hear that higher education is a tool to attain a higher paying job, not a fulfilling career. His experience suggests that connecting passions and talents with learning and a professional career may be a crucial part of helping students facing significant economic and personal hurdles persevere and find fulfillment. And many of the college access educators he interviewed agreed. All of this points to the possibility that underrepresented students — those who are least likely to graduate from college — may benefit the most from gaining the purpose and direction gap years provide.

Of course, it’s important to note that colleges and universities also benefit from gap years. Higher education is in crisis, not just because tuition costs are skyrocketing and saddling vulnerable students with debt (particularly the 43% of low income students who start but don’t graduate from college), but also because they are failing to deliver educational value that matches the cost of attendance. Gap years that prepare students to learn more and contribute to the campus community can be a crucial means of ensuring students graduate prepared for careers and fulfilling lives. That is the outcome that will justify the tuition costs to students and parents.

Higher education is also facing challenges related to adequately supporting students on campus. Our team at TBB has written about how the non-traditional format of gap years creates an unparalleled space for necessary student support around substance abuse, mental health, and helping boys become ethical men. These issues are related to major challenges that are on the rise for campuses, leading to sexual assault, emotionally and physically unhealthy students, and underperformance in learning spaces. Providing an intentional time and space for students to work with adequately trained mentors equivalent to that offered by intentionally designed gap years could result in significant improvements in student learning, growth, and campus life.

Expanding Access to Gap Years

There are educators throughout the US who are deeply committed to creating access to gap years for all students. The American Gap Association is working to raise awareness about the value and need for more gap year access with legislators. Gap year providers are raising scholarship funds and creatively recruiting students. And educators, students, and families are taking risks to make a gap year a reality.

But, more work needs to be done. First, research needs to be expanded to help us understand the true impact of gap years on students and higher education. While measuring effects on academic performance is important, studies should also assess the impacts on fulfillment in career and life for gap year participants. Also, research must begin to identify the gap year practices that result in the best outcomes. Much of the current data lumps gap year participants together without differentiating among the types of learning experiences and supports they had during their gap year. Educators in this space will benefit from knowing best practices.

Second, a broad effort to share the findings of research that measures the impacts of gap years must be brought to students, families, educators, university administrators, and education funders. These stakeholders each play a role in assessing the potential and value of a gap year to their work in the education sector.

Finally, new models for providing, funding, and leveraging gap years should be developed. The current model of adding cost and time to the college process for most gap year students is untenable in the long term. This will seriously limit the growth of the sector and access to gap year programming. One model to consider is to reimagine gap year as part of the undergraduate experience. Taking lessons from existing gap year providers, colleges and universities can create programs for the first semester or year that merge academic rigor with the personal growth that results in purpose and direction for students. Either through developing proprietary programs or partnering with existing gap year providers, higher ed institutions can design programs and curricula that tie directly into existing courses of study on campus while creating small learning communities that will serve the students and faculty well throughout their time on campus. Perhaps most importantly, this model dramatically expands access to the benefits of gap year programming. It ensures that federal financial aid and traditional scholarship sources will apply to these experiences. It also means that a gap year type experience does not require students to add the time for that program onto the time they were already committing to college. The study abroad market in higher ed offers a strong set of examples of how to build gap year learning into the college experience.

Gap years are associated with privilege. But, privilege is not inherent in this educational opportunity. Done well, intentionally designed programs for students in the college transition result in powerful learning and growth that serves students and universities well. Further research to better understand this value and how to expand it can be matched with innovative thinking in higher ed to ensure every student benefits from the crucial outcomes gap year students receive today.