Media

Mean World vs. Kind World

Have a negative outlook about the world? A little kindness can lift your mood.

Posted July 3, 2023 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Key points

- Negative exposure to media can cause people to believe the world is more dangerous than it really is.

- Viewing the world in this way can also cause anxiety, fear, general pessimism and hypervigilance.

- Simply viewing or reading about kindness can alleviate feelings of hopelessness.

- Emotion “elevation” can lead individuals to want to become better people themselves.

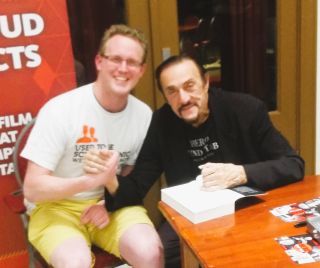

The city of Nijmegen, Holland, founded in the year 98, is perhaps best known for being the oldest town in the Netherlands. But in the coming years, it might arguably be credited as the starting point of an international effort focused on good deeds. The person responsible for this is Lerrie Grooten, who has made it his life’s work to spread kindness throughout the world. Grooten was a University student when he started down this path in 2016. He had just attended a lecture in Nijmegen, his home town, by one of this post's authors – Phil Zimbardo – about the Heroic Imagination Project (HIP). HIP is a non-profit that educates students, organizations and companies, using a combination of psychological research, intervention education, and social activism to help create everyday heroes equipped to solve local and global problems.

The ideas in the lecture, like being willing to tap into the hero within you when needed and sharing simple acts of kindness with those you know — and those you don’t — resonated with Grooten. In the days that followed, he started practicing some of the exercises suggested in the lecture, such as giving someone a sincere compliment every day for a week. He noted that doing small good deeds like this not only brought a smile to the recipient, but also elevated his mood and outlook on life.

Then Grooten decided to spread the ideas in his home country. He created a website focused on the benefits of practicing random acts of kindness and “paying it forward” – doing something nice for someone for no particular reason. He wrote a blog and after receiving positive feedback from his readers, he emailed local and national media about spreading random acts of kindness to uplift strangers. This led to radio and newspaper interviews and eventually a front-page article in the Netherland’s largest newspaper, De Telegraaf, about the 170 acts of kindness Grooten bestowed on others in a period of 21 days. Then he organized a Kindness Month during which he single-handedly performed 2,210 acts of kindness within August and challenged people globally to do just five acts of kindness during the month. To his delight, he received emails from around the world and discovered that thousands of people had participated.

Grooten continued to nurture the seeds planted during the HIP lecture. His enthusiasm and innate goodness touched thousands, and eventually millions, of people looking to do a little good in what many perceived to be a world of pain.

Good news vs. bad news

In 2017, University of Essex psychology professor Kathryn Buchanan and her colleague Gillian Sandstrom commenced a study recently published in PLOS One titled “Buffering the effects of bad news: Exposure to others’ kindness alleviates the aversive effects of viewing others’ acts of immorality." In a Washington Post article about this research, Buchanan said she was spurred to conduct the study after experiencing intense emotions following the shocking news of a suicide bombing at a concert in London in which 22 people were killed. She knew that absorbing horrific news can have negative effects – anger, anxiety, depression, hopelessness, heightened stress – on a reader or viewer.

However, in the flood of tragic news stories, she noticed that there were also reports of compassionate people offering food, rides, and donating blood. Hearing of these kind deeds comforted Buchanan and gave her hope there is good in the world. She wondered if what she felt was unique to herself or if others also experienced being uplifted by good news after being exposed to bad news. What her study revealed is that negative exposure to media can cause people to believe the world is more dangerous than it actually is; but when we see kindness in others, we can have faith that the world isn’t as bad as the headlines might lead us to believe.

Mean world syndrome

In the 1950’s, journalist, educator and World War II Bronze Star recipient George Gerbner commenced a decades-long deep dive into the effects of long-term moderate-to-heavy exposure to violence-related mass media. In the 1970s, Gerbner suggested the theory of “mean world syndrome” — that, over time, an individual can develop cognitive bias and see the world as more dangerous than it actually is, especially when subjected to violent news reports and television shows. Because mean world syndrome causes one to perceive threats where and when none may exist, it can also cause anxiety, fear, general pessimism, and hypervigilance.

Gerbner’s work continues to expand. An article in the APA Monitor — “Media overload is hurting our mental health” — references several studies, starting in 2016, in which psychologists noted an increase in news-related stress. They discovered that, at their worst, some overwhelmed, media-saturated patients can develop a sense of learned helplessness. Their solution? Installing media guardrails, such as turning off notifications, adding tech-free periods throughout the day, and limiting social media checks to 15 minutes. Across the board, these researchers agreed that patients should be encouraged to “be more proactive in issues they care about rather than just a passive observer of the news.”

Elevation

To further combat the symptoms that too much media – especially the negative kind – can instill in us, let's explore the positive emotion psychologist Jonathan Haidt calls “elevation.” In an APA article from 2000, Haidt stated, “Elevation appears to be the opposite of social disgust. It is triggered by witnessing acts of human moral beauty or virtue. Elevation involves a warm or glowing feeling in the chest, and it makes people want to become morally better themselves…elevation increases one's desire to affiliate with and help others." Some examples that may cause us to experience elevation are seeing someone go out of their way to be kind and help an elder, or bravely risking their life to save another, or putting self-interest aside in order to be honest and tell the truth. These selfless acts can be viewed in person or through the media.

When we last checked in with Grooten, he was back in the news spreading the word about practicing random acts of kindness for strangers and paying it forward. Along with Rosalie van Woezik, Grooten formed Kindness Collective Nijmegena, through which they and others organize kindness events. For instance, in 2021, the group performed 25,000 acts of kindness throughout the world and put forth a clarion call to action for all who want to work together to build a kinder, more compassionate world. Grooten told us, “We hope to show the way forward to people, to touch people’s imaginations and put young people on this path.”

We hear you and see you, Lerrie. You elevate us.

References

Buchanan, K, & Sandstrom. G.M. (2023). Buffering the effects of bad news. San Francisco, CA: PLOS One.

Delft Institute of Positive Design Staff. Elevation. Delft, The Netherlands: Emotion Typology.

Gifford, B.E. (2020). What is mean-world syndrome? Watchetts Ward, Surrey, UK: Happiful.com

Huff, C. (2022). Media overload is hurting our mental health. Washington, DC: APA Monitor.

Haidt, J. (2000). The positive emotion of elevation. Washington DC: APA

Page, S. (2023). Good news stories can ease the angst of upsetting news. Washington, DC: The Washington Post.