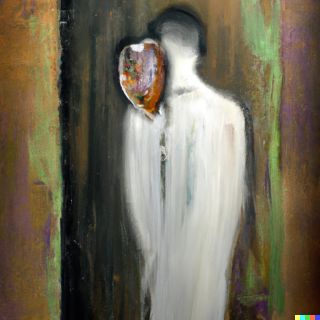

Ghosting

Why Ghosting Is a Form of Relational Aggression

Goodbyes are inevitable. Hurting others shouldn't be.

Posted May 15, 2023 Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

Key points

- Poorly resolved relationships perpetuate distress and lack accountability.

- Ghosting disregards the other person's thoughts, feelings, and points of view.

- Learning how to make positive transitions leads to positivity and growth.

Our lives are always in flux. As humans, each day brings new experiences that require growth, adaptation, and transformation. It is the same with our relationships. They change, evolve, and eventually reach their end. Romances fade, friendships are outgrown, one job gives way for another, and death is our inescapable fate. While farewells are inevitable, many people are terrible at saying goodbye.

It is natural to feel uncomfortable about change and transition. We carry myriad defenses for protecting our hearts, but avoidance is a favorite. Relationship endings are rarely easy. They can be emotional and fraught. When compounded by conflict, transitions can evoke anger, sadness, and regret. It is no wonder that we might want to push past endings quickly or avoid goodbyes altogether to minimize the discomfort. However, all endings represent turning points.

Avoiding uncomfortable endings establishes an unhealthy pattern of incomplete relationships. Relationships that have been poorly resolved hold us in the past, leaving remnants of regret, anger, confusion, and guilt, whereas fully resolved relationships allow us to move confidently forward to consciously embrace new beginnings. Positive transitions are wholesome, intentionally providing a path for flourishing.

Research shows that endings are often what we most remember about relationships, due to the recency effect, where the last words, events, feelings, or conversations create the strongest recall (Fredrickson, 2000). Goodbyes are an opportunity to put our emotions into words, shape how we remember the relationship, and receive a sense of closure. Schwörer, Krott, and Oettingen (2020) refer to relationships marked by a sense of closure as “well-rounded endings. Specifically, people describe an ending as well-rounded when they feel that they have done everything they could have done, that they have completed something to the fullest, and that loose ends have been tied up. Well-rounded endings are associated with positive affect, limited regret, and a constructive transition into the next phase of life, where one is not compelled to think about or act on missed opportunities and undone actions.

Many relationships are time-limited, but even brief encounters that are platonic or with business associates are connections between people that deserve appreciation. There is no need to stay in a relationship that has stopped working for you. It is fine to allow a relationship to end, but the fact that a relationship no longer serves you does not mean that it never mattered. People and relationships always leave behind a trace, a memento of the affiliation. A positive farewell honors the alliance, shows respect for the interpersonal connection, and validates the impact the person has had on us and any ripples it might affect.

Ghosting

Ghosting is a form of relational aggression where someone suddenly ceases all communication and contact with another person without any apparent warning or explanation and ignores any subsequent attempts to communicate. Ghosting is often used to avoid conflict but it is fundamentally a destructive move, triggering feelings of confusion, distress, and humiliation in the person who is ghosted.

Emotionally, being ghosted triggers feelings of vulnerability, doubt, and lowered self-worth. At a physiological level, ghosting depletes neurotransmitters, activates abandonment and rejection wounds, activates a systemic experience of loss, and activates the same neuropathways as physical pain (Krossa et al., 2011). To ghost someone is to make an intentional, self-centered decision to leave a situation in a manner that inflicts trauma and shame while leaving the recipient without a voice. In this way, ghosting is an act of narcissism. It is an act of discarding another, without empathy, completely ignoring the other person’s feelings or needs. Further, ghosting precludes an acknowledgment that the goodbye is what the ghosting person wants, blaming it instead on circumstances or the other person. It inherently distorts reality, allowing the ghoster to deny all responsibility for their behavior.

Healthy Endings

No one likes having difficult conversations, but that is exactly what healthy endings require. Having a two-way conversation is important to allow both people to voice their points of view and feel heard. Hearing each other out demonstrates respect for one another’s feelings and allows for honest contemplation and, then, closure. We must learn to reflect one another that, while it may be time to move on, we still acknowledge our shared time and humanity.

In taking responsibility for saying a humble goodbye, we make the world a little bit better. Standing grounded in the awareness that how we say goodbye is an important part of creating a connected society, we move forward compassionately, engendering new spaces for active listening and deeper future connections.

We always have a choice about how we handle transitions. How you leave relationships creates an emotional residue that accumulates inside you. A decision to honor the end of a relationship, to take personal responsibility for actions that promote mutual healing, leaves vestiges that build strength and positivity. Learning how to approach transitions with grace and respect gives rise to positive self-growth, resilience, self-efficacy, and the ability to build a healthy future for oneself in future relationships.

Facebook image: evrymmnt/Shutterstock

References

Fredrickson, B. L. (2000). Extracting meaning from past affective experiences: The importance of peaks, ends, and specific emotions. Cognition & Emotion, 14(4), 577–606. https://doi.org/10.1080/026999300402808

Krossa, E., Bermana, M., Mischelb, W., Edward E. Smith, and Wager, T. (2011). Social rejection shares somatosensory representations with physical pain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), 108 (15), 6270–6275, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102693108.

Schwörer, B., Krott, N. R., & Oettingen, G. (2020). Saying goodbye and saying it well: Consequences of a (not) well-rounded ending. Motivation Science, 6 (1), 21–33. https://doi.org/10.1037/mot0000126