Defense Mechanisms

Beware the Regression Fallacy

Firing Coaches May Seem to Help Sports Teams, But It May Just Be an Illusion

Posted January 4, 2014

With the National Football League (NFL) regular season now over, sports fans once again bore witness to the morbid annual ritual called “Black Monday,” in which the head coaches of losing teams are mercilessly purged. Like clockwork, it happened again this year, except that the bloodbath began a day early: the Cleveland Browns were apparently so eager to dump Rob Chudzinski that they couldn’t bring themselves to wait until the Sunday clock struck midnight. The other head coaching casualties so far this week have been Minnesota Vikings’ Leslie Frazier, Detroit Lions’ Jim Schwartz, Washington Redskins’ Mike Shanahan, and Tampa Bay Buccaneers’ Greg Schiano. The professional sports teams that follow in the hallowed tradition of wiping the slate clean in the wake of disappointing seasons are surely persuaded that doing so will boost their records next year. Are they right?

Probably not, although it is no wonder why they - and their fans - would think so. After all, the chances are high that most of these teams will do better next season, fueling the perception that the firing decisions were well-advised. In fact, this perception is almost certainly a cognitive illusion. Were the teams merely to wait a year and do nothing, they would discover that their records would usually improve anyway. In 2007, a Ghent University research team compared the records of Belgian soccer squads that fired their coaches after a losing spell with those of comparable losing squads than didn’t, and found no differences. Both groups of teams improved shortly afterwards.

What’s going on here? The teams are neglecting a pesky statistical phenomenon termed regression to the mean. Math phobic readers need not worry: regression to the mean is easy to understand with no specialized training. The phenomenon was recognized in the late 1800s by Charles Darwin’s cousin Sir Francis Galton, who noticed that extremely tall fathers tended to have children who are slightly shorter than they are, and that extremely short fathers tended to have children who are slightly taller than they are. Regression to the mean tell us that extreme scores tend to become less extreme over time. Regression, as statisticians call it, is not a hypothesis: it is a mathematical necessity whenever a phenomenon is unstable over time. Needless to say, virtually all things in life, whether they are the performances of NFL teams, the trajectories of stocks, or the behaviors of romantic partners, bounce around in unpredictable ways. As the old saw reminds us, what goes up must come down, although because the converse is also true, virtually all losing teams will reverse their fortunes eventually.

Because few people are aware of the regression effect, they readily fall prey to the regression fallacy – imputing spurious causal significance to phenomena that are just due to regression to the mean. Here’s why. They are committing the understandable error of assuming that because event A preceded event B, event A must have caused event B. Yet, the fact that all serial killers watched television as children doesn’t mean that the small screen is a recipe for later lethal violence. Because of this error, people overlook the regression effect and instead search for any number of plausible causal narratives for unexpected changes over time. Most of these hypotheses are explanations in search of a phenomenon, because there is often nothing left to explain: the shifts are attributable to regression.

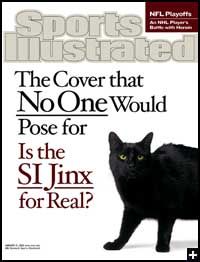

As New York University psychologist Justin Kruger and his colleagues have observed, a plethora of everyday phenomena stem from the regression fallacy. Like most jinxes, the Sports Illustrated jinx nicely illustrates this mental mirage. On November 18, 1957, the magazine featured the University of Oklahoma football team with the headline “Why Oklahoma is Unbeatable,” in reference to the Sooners’ 47 game Division 1 winning streak. They blew their next game. Most recently, on November 20, 2013, the seemingly unbeatable University of Alabama quarterback A.J. McCarron graced the Sports Illustrated cover, only to lose in a stunning upset to Auburn the following week. The jinx is so notorious that some athletes refuse to appear on the magazine’s cover. What they are forgetting is that to make the cover of Sports Illustrated, one almost always needs to achieve a spectacular triumph; such success would seem to set one up for a mighty fall. True, but the fall is a matter of statistical probability; a player or team that keeps winning will eventually lose. Athletes’ careers are indeed slightly more likely to nosedive after they appear on magazine covers, but not because they appear on magazine covers. Like all statistical phenomena, though, regression is merely a group tendency, so it doesn’t apply to all individuals: Michael Jordan’s 49 Sports Illustrated cover appearances certainly didn’t seem to dent his career success.

The “movie remake phenomenon” is another delightful example. Most movies remakes or sequels are worse than the original. Think of the notoriously awful follow-ups of Psycho, Swept Away, and 2001: A Space Odyssey, among scores of others. Many a film analyst has sought to explain the reasons for this phenomenon: directorial hubris, fewer resources for the second film, audience fatigue. Yet again, the phenomenon may need no explanation. Only successful films tend to be remade, so the second film is likely to fall short of the original. We rarely recognize this fallacy because decisions to remake films are asymmetrical. If a masochistic Hollywood film producer bothered to remake the recently released “47 Ronin,” arguably the worst film flop of 2013, he or she would probably discover that the mulligan would be more successful. When one loses over $100 million dollars on a movie, there’s no place to go but up.

Nowhere is the regression fallacy more pervasive, and arguably more pernicious, than in physical and mental health treatment. Most people seek physical or psychological help when their difficulties have reached a breaking point. In other cases, such as obesity, they may decide that the jig is up when their repeated change efforts prove fruitless. In both cases, these are precisely the cases in which regression to the mean is maximized, because their problems have reached their most extreme levels. Not surprisingly, they are also the very instances in which people are most prone to being fooled by ineffective, and even harmful, interventions. Most historians of medicine tell us that prior to the 1890s, the substantial majority of “treatments” were at best worthless. Today, we look back at blood-letting, leeching, and purging with dismay. What we overlook is that these well-intentioned treatments “seemed” to work, because the maladies for which they were intended improved over time following – but in spite of, not because of – these interventions.

In an article to appear later this year in the journal Perspectives on Psychological Science, my co-authors (Lorie Ritschel, Steven Jay Lynn, Robert Latzman, and Robin Cautin) and I delineated 26 reasons why people can be misled into believing that ineffective or even harmful psychotherapies are effective. Perhaps best known is the placebo effect, or improvement due to the mere expectation of improvement. Yet of all 26 reasons, the regression fallacy may account for more erroneous inferences than all other 25 explanations put together. People seek psychological treatment when their problems are at their worst; as a consequence, they will often improve regardless of the intervention.

This point bears important implications for recent debates concerning the advantages and disadvantages of evidence-based practice, which places a premium on using controlled clinical research to inform treatment selection. Evidence-based practice has been vigorously resisted by some psychotherapy practitioners, in part on the grounds that it devalues clinical intuition and clinical experience when choosing interventions. Yet whatever its drawbacks, evidence-based practice has the essential virtue of minimizing the risk of the regression fallacy, because randomized control groups are roughly equated in their odds of regression to the mean.

We should remember the regression fallacy when making our New Year’s resolutions. Millions of us will decide to finally quit smoking, lose weight, or stop nagging our spouses, and some of us will even end up doing so soon thereafter. But we should remind ourselves that, like that of many NFL teams, the success of our annual ritual may be more apparent than real.