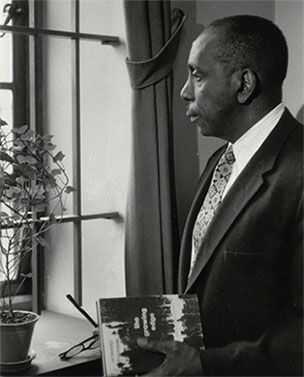

A dear friend in Austria, who is a theologian and Christian, gave me a dog-eared copy of his book Jesus and the Disinherited, written by Howard Thurman.

Thurman was the Dean Emeritus at Boston University. Upon closer exploration of this man, I learned that he was not only a theologian, but also a philosopher, educator, and civil rights leader. In fact, the text, published in 1949, deeply influenced Martin Luther King’s social justice approach via nonviolence.

He gave this precious book of his to me that he said got him through very dark times in life. It was a powerful gift to share something that had so much meaning to him and that I saw he carried with him most everywhere. He also added that, he basis his faith on “the Jewish foundations of Christianity and of the Jewishness of its founder.”

And I read it.

There is something oddly consoling that the themes with which man has been challenged, whether 2,000 years ago, in 1949 when this text was published, or today, have a familiar pattern. As social animals, we find safety and security in the “same.” It is perhaps about tribal affiliation. However, to have such an in-group identity, it seems as if humankind continues to create out-groups.

It is well-known in the field of public health, for example, that if you want to make a population sick, marginalize that group of people. It doesn’t require a lot of historical reflection to see how this is consistently true whether in hindsight or today. Whether discrimination takes place on the basis of gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, beliefs, geographic location, or a multitude of other differentiators that we as a species create all of them land at the detriment of “the other.”

Wrongly, I tend to stand back with materials that have references to Jesus in them. As a secular Humanist, I don’t embrace the supernatural narrative of Jesus. However, I do see in him a wise individual who mobilized resources as a leader to create needed social change at a time of the widespread exclusion of many.

I am happy that I didn’t allow the title of the book keep it at an arm’s length. Thurman reaches out to “all of those who stand with their backs against the wall” for individuals to “… live in the present with dignity and creativity.” Today there are many of us “cornered” including the homeless, the drug-addicted, refugees, unemployed, under-employed, those discriminated against, those alone, those alienated, and those simply trying to find a professional place in society.

From a historical perspective, Jesus’ followers were those marginalized by the power-holding elite. Jesus, a poor Jew, proposed a perspective that was deemed antagonistic to those who held power. These elites were threatened by any challenge to their status and their ongoing security of it. This teacher, Rabbi, preacher, and leader, however, included these “disinherited and disadvantaged” into his community. The oppressed had a sympathetic and empathetic leader in Jesus.

Today, we see elitism in the form of the “1 percent,” and a continuing chasm growing between the have and have nots in this world. Human behavior certainly includes patterns of behavior that repeat themselves.

Central to Thurman’s text are what he describes “three hounds of Hell:” fear, hypocrisy, and hatred that have motivated destructive behavior to over the course of time to self and others. Jesus, he argued, saw little change possible to man and his communities without overcoming these “hounds.”

“In the absence of hope, ambition dies, and the very self is weakened and corroded. There remains only the elemental will to live and to accept life on the terms that are available.” H. Thurman

The Hounds of Hell

Fear

Fear (and its related feelings of anxiety and despair) activates our so-called reptilian brain and moves us into a reactive mode of functioning that often overrides rationale to protect the survival of an organism. It is a powerful emotional and biological response that moves us to action. It can also be manipulated for the purposes of maintaining power, scuttling the opportunity to consider empirical facts and solutions that go beyond violence or wall-building. A culture of fear is easy to stir up in today’s world. The outcome is an increase in the sale of security systems, fences, and guns as well as a hyper-aware state of any threats around one. It destroys community as we come to fear one another rather than cultivate trust and connection and a sense of individual identity so critical to the health of and well-being of any individual.

Almost daily, we promote feelings of inferiority by the way we (individuals, groups, state, nations) treat those who didn’t pull themselves “up by their boot straps.” We may make people feel “less-than” because of their age, looks, profession (or lack of), body shape, sexual orientation, political orientation, type of car driven (and so on so forth). How can we promote the dignity of the individual through social interaction and policy that reduces this segregation? Emphasizing a sense of personal worth through equal opportunity will go a long way.

Hypocrisy

The chasm between integrity and hypocrisy is a tremendous one. I fine that I feel at my best when I act with integrity in the world (this is nothing new to understand); and when I act with deception I know it and it doesn’t feel right. Today I see a culture of insistent truths (assumptions and perspectives stated as truth because they are firmly repeated and any contrary argument or perspective is summarily dismissed ) at the expense of reality, science, and fairness. There are many moral compasses going astray without question; but there are also many moral compasses that are steadfast.

Historically, we have seen that this sort of hypocrisy can be changed, but it takes the mobilization of resources, especially within the ranks of those who are “disinherited” from these revised “truths.” Change is often slow and requires loss which is difficult.

Hatred

This aspect of human behavior is as old as humans have treaded upon this earth. We all know how hatred has led to the destruction of people, place, and beauty. And hatred can be long-lasting passing from generation to generation. When there is a shift in a system, for example politically in the former Yugoslavia, witness how quickly age-old hatreds emerged as communism fell. Another example is the challenge of finding peace in the Middle East. Sadly, hatred becomes more entrenched with each successive generation exposed to violence and destruction. Additionally, 21st century life makes many feel less included, more isolated and or alienated, and “impersonal.” Thurman points out that as a lack of authentic human interaction lessens, seeds of hatred are sown.

Even the most resilient individuals can give into bitterness with too many setbacks in this world. Not being afforded basic human rights that provide certain protection and privileges demoralizes and robs identity and a sense of opportunity for many.

Change

If one reduces and even removes shame and humiliation, there is greater opportunity for genuine interaction as well as a sense of hope and help which is so fundamental to healthy human functioning. To me, many of us are seeking authenticity and so-called real interactions where we are heard, understood, and held in some manner. I often hear in my therapeutic practice that “I just want to be known and respected.” It seems as if it is request that we can offer to another, but in day-to-day life, it is often a scarce quality. How can one forget how after the 9/11 terrorist attacks people reached across typical lines of division to console, support, and be together. Perhaps this took place because we felt a common threat greater than the divisions we maintain in daily life. Yet it was short-lived.

Over the summer, I want to reflect on the following questions in this blog that have emerged from this book and I hope you join me in thinking about this:

- How do we live in today’s world without losing our humanity?

- How do we address the misuse of power of the strong against the weak?

- How do we become more expert followers of leaders who may lead us towards constructive outcomes rather than destructive ones?