Last week, on September 25, President Obama gave a lecture at the United Nations in New York. He strongly condemned any offenses against people of faith. But, in one of his finest moments, he defended free speech. “Given the power of faith in our lives, and the passion that religious differences can inflame, the strongest weapon against hateful speech is not repression; it is more speech—the voices of tolerance that rally against bigotry and blasphemy, and lift up the values of understanding and mutual respect.”

In that spirit, it may be worth pointing out that most of the world’s great religions have something to do with sex. Most of the world’s sacred texts are hundreds or thousands of years old. And in the old days, people took it for granted that some men would have access to more than one woman. From the Hebrew Bible, to the Bhagavad Gita, to the Acts of the Buddha, to the Confucian Classics, to Christian emperors from the East to the West, patriarchs and princes filled their palaces with wives. Some had a couple of women. Others had thousands of them.

Many religions turn inward. They speak up for the poor and meek; they ask us for charity, and they ask us to stay chaste. But every sacred text is set in a historical context. And all are in some way the products of people of flesh and blood.

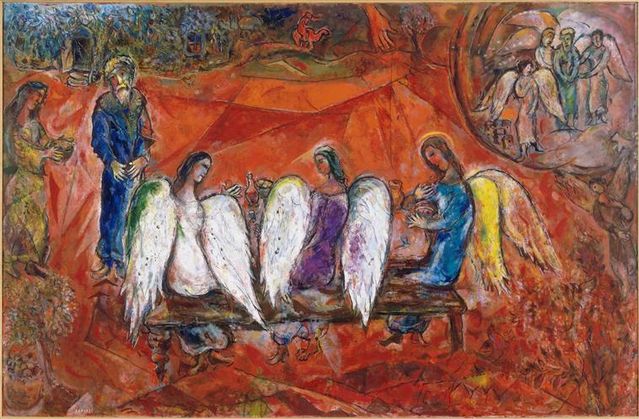

Once upon a time, there was a man named Abram. He made a covenant with his God, who said: “No longer shall your name be Abram, but your name shall be Abraham; for I have made you the father of a multitude of nations” (Genesis 17:5). Abraham had a son by his wife, Sarah; he had another son by Hagar, who was Sarah’s maid; and he had 6 sons by Keturah, after Sarah died. But some of his grandsons outdid him. Jacob had 12 sons by 4 women—6 by his wife, Leah; another 2 by his wife, Rachel; and another 4 by Bilhah and Zilpah, his wife’s maids. So Jacob had his own conversation with the lord, who said: “Your name shall no more be called Jacob, but Israel, for you have striven with God and with men, and have prevailed” (Genesis 32:28).

Generations later, some of Israel’s descendants became kings. David lived in an ivory palace, surrounded by ladies of honor and virgin companions; the Bible names one of his daughters, and 19 of his sons. But his son, Solomon, was much more ambitious than he was. “He had seven hundred wives, princesses, and three hundred concubines; and his wives turned away his heart” (1 Kings 11:3).

Long before Solomon, there were kings in South Asia. And at the heart of the Sanskrit epic, the Mahabharata, is the Bhagavad Gita—a conversation between prince Arjuna and lord Krishna, his guide. They talk about renunciation—about casting off hate and desire; about living alone and eating little; about keeping their minds and bodies controlled; about forsaking ego, might, arrogance, desire, anger, graspingness and possessiveness, so that they could live at peace.

But in other parts of the Mahbharata, pretty girls dance “by the thousands” when Arjuna marries the flawless princess, Draupadi. And the lord Krishna, whose 8 wives give him 80 sons, captures thousands of women from the evil Narakasura. After which, his first wife is flattered: “You are considered and worshipped as eldest of all 16,000 wives of Krishna.”

Sometime in the 6th century BC, Siddhartha Gautama, a prince from the Himalayas, sat under a fig tree and became enlightened. He found an eightfold path to nirvana--right views, right resolve, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness and right concentration. And he added 5 precepts. Do not kill, do not steal, do not lie, do not drink and do not be unchaste.

But centuries later, the Buddha’s biographer remembered that when Siddhartha was a young man, women waited at his windows to see him (“crowded together in the mutual press, their earrings ever agitated by collisions and their ornaments jingling”). Or they surrounded him as he walked in his gardens (“like an elephant through the Himalayan forest, accompanied by a herd of females”).

Siddhartha’s contemporary, Kong Fuzi, better known as Confucius, was brought up in poverty. But the Analects—put together by his followers, in the first generations after his death—include this line from Confucius, which they printed twice. “I have never seen anyone who loved virtue as much as sex.”

Roughly 3 centuries after Kong Fuzi, China was unified by the First August Emperor of Qin. His successors promoted a civil service, whose applicants studied Confucius. Most Confucian scholars didn’t bother with mathematics—which was left to the merchants. And they didn’t bother with technology—which was left to the trades. Instead, they studied the Classic of Poetry, the Classic of Changes, and the Classic of History—full of irresponsible overlords (“abandoned to drunkenness and reckless in lust”), and consorts who padded through their palaces at night (“modestly we walk through the dark, carrying our own quilts and coverlets”). And they supported emperors like Qin Shihuang--who built China's Great Wall, and kept 10,000 women at home; and they supported emperors like Yangdi--who rebuilt China's Great Wall, and kept 100,000 women in his palace at Yangzhou alone.

Close to 6 centuries after Siddhartha or Kong Fuzi, and an undetermined number of years after Arjuna or Abraham, Jesus of Nazareth was born. None of the gospels—put together by his followers, in the first generations after his death—say that Jesus had a wife. And the gospels of Luke and Matthew say that Jesus was the son of a virgin. “When his mother Mary had been betrothed to Joseph, before they came together she was found to be with child of the Holy Spirit,” says Matthew; “The Holy Spirit will come upon you, and the power of the Most High will overshadow you; therefore the child to be born will be called holy, the Son of God,” says Luke (Matthew 1:18; Luke 1:35).

In the nearly 2 millennia since, many Christians have been celibate or chaste. But many have not. It was in the spring of AD 313 that Constantine the Great drew up his Edict of Milan, promising religious toleration in Rome. Most of Constantine’s Christian friends would remember him as a faithful husband: "He observed a chaste and pure rule of life, offering up his prayers to God," wrote the bishop of Caesarea. But a few apostates dissented. “He gave all his attention to pleasure,” the emperor Julian wrote.

And half a millennium later Charlemagne, who was considered the Father of Europe, and made an emperor at Christmas in the year 800 by the pope, was admired by the abbot who wrote about his life--because he had 4 concubines and 4 wives. “His sons rode at his side and his daughters followed along behind. Hand picked guards watched over them as they closed the line of march.”

Mehmed II conquered Constantinople in 1453, he put up Topkapi palace and filled it with women and eunuchs. There were 150 splendid, well kept and beautiful women in it when a Genoese merchant stopped by; and privy purse records suggest that those numbers grew to 436 women--with another 531 at the Old Palace--by 1652. Centuries after Hindus, Hebrews, Buddhists and Christians put together harems in the Near and Far East, Islamic emperors from Iberia to Indonesia collecting believing women and 2, 3, or for wives apiece (Quran 4:3, 33:50), who were often looked after by sterile castes.

These days, the world is a more egalitarian place than it was. Thousands of years after Charlemagne or Constantine or the First Emperor of Qin, and thousands of years after stories about Arjuna or Siddhartha or Abraham or Muhammad were written down, fewer women are herded into harems. And fewer men have to live without wives.