Education

Stages of Learning About a Person

We learn about one another over time.

Posted February 3, 2014

We human beings have a keen interest in observing and learning about one another—an interest that psychologists now trace back to our evolutionary roots. Among our ancestors, those who paid attention to people and understood how they functioned could better navigate their social world. These talented observers of people were a little bit better at predicting who would make a good ally, who to dig a well with, who would be a good mate, and who to avoid whenever possible. Ultimately, I believe, this ability to understand others and forecast their behavior evolved as part of what I call personal intelligence—the ability to learn and reason about personality in oneself and others.

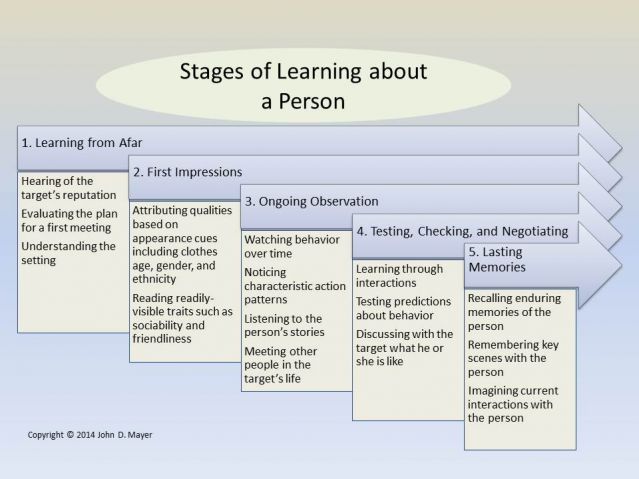

We use personal intelligence to get to know other people over time. One good way to describe this "getting to know you" process, I believe, is to divide it into the stages we go through as we learn more about a person. I've identified five such stages, beginning from before we have met a given individual to reflecting back upon her after she may no longer be a part of our life. Each of the stages I've identified has, mininmally, been the subject of theoretical discussion, and often includes as well extensive empirical research into the learning processes about a person that are involved.

In the first stage, “Learning from afar,” we collect information about the person we’re going to meet. We might be told by others what the new person is like and get a sense of the individual’s reputation. If someone has arranged a meeting for us, we may guess something about our new acquaintance from the meeting place (“He wants to meet you in a coffee shop…”) or the proposed time ("…but not before 11 A.M."). And nowadays, of course, we can Google the person before we meet him.

The “First Impressions” stage (Stage 2) begins when we encounter the person face-to-face. In it, we attend to the target person’s outward appearance and other observable characteristics and signals. Social psychologists tell us that we quickly perceive information about the person’s sex, age, ethnic background, and the like. From the standpoint of being judged, more than a few of us feel uncomfortable being assessed in this way—it feels like we’re being lumped into one or more groups, some of which may not describe us well. From the observer’s standpoint, however, these evaluations can be of pragmatic help. As observers, we will make different forecasts regarding the behavior of a seven-year-old than of a 30-year-old. And this isn’t all bad—for example, we’ll be especially cautious steering our car into a driveway if we see a seven-year-old there—and rightly so.

If we are wise observers, we’ll move as quickly as possible to more personalizing information. Even in a first encounter, people may quickly signal the degree to which they are outgoing and sociable versus quiet and shy, and the degree to which they are agreeable versus disagreeable. Psychologists refer to our impressions at this time as taking place at “zero acquaintance”—and we can be fairly accurate during these first encounters about a few highly visible traits (but not for others).

In the “Ongoing Observation” stage (Stage 3) we watch a person over the longer term. A.A. Roback, a founder of personality psychology, wrote about how the superficial charms that we experience at “zero acquaintance” and early in a relationship can wear thin and how deeper attributes become more important: “It is evident that in due course the charm…wears off for the friend of long standing,” he said, “and the deeper or inner personality begins to stand out.” During this stage we learn more about how the target person views herself. We monitor her actions and examine any discrepancies between her appraisal and her behavior. (Some psychologists suggest that there is a kind of negotiation between the target and observer as to what the target is like.)

In the fourth stage—“Testing and Checking”—we learn about others by testing our predictions about their behavior, and perhaps by changing how we act with the target and seeing how the target acts in response. For example, we might predict that an acquaintance of ours will be likely to throw a party over the holidays and see if that truly transpires. We might also believe that a friend can (and needs) to hear some supportive criticism and see whether the friend can hear such comments from us or whether she is defensive. (Of course, some of our friend’s reaction will depend on our tact, timing, and relationship).

Finally, in “Lasting Memories” (Stage 5) we have key recollections of the person that we can readily call to mind. And, for our most important relationships, we have internalized an image of the person that is so vivid that we may hear him talking to us even when he is not present, or indeed, even if he can no longer be present owing to separation or death. His memories are within us as a kind of inner avatar with whom we can commune.

One aspect of these stages that intriques me is that I suspect there are considerable differences in how much people learn at each stage. For example, some people are able to glean many more cues during “First Impressions,” than are others. Or, in the “Testing, Checking, and Negotiating" stage, some people are very active in engaging with another person, predicting how they will act and testing their hypotheses about the person; others may be far less inquisitive in this regard. Over time, some people may learn far more about a specific person than will others.

If we care to learn more about the people around us—a goal some of us share—then thinking about our understanding in terms of these stages may allow us to reflect on when we do our best learning about others and in which stages we might want to improve our observational skills.

References

“It is evident…” p. 159, ‘Double Phase of personality,’ ‘Defining the terms’, in A. A. Roback, (1931)\. The Psychology of Character. Universal Digital Library. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/psychologyofchar010525mbp

Some psychologists suggest… See the discussion on p. 885 of Colvin, C. R. & Funder, D. C. (1991). Predicting personality and behavior: A boundary on the acquaintanceship effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 884-894.

Copyright © 2014 by John D. Mayer