Coronavirus Disease 2019

The Future Is Looming

How to confront a culture of extraction that threatens extinction.

Posted April 8, 2021 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Last week I participated in a Zoom seminar in which anthropologists and philosophers present works in progress. The theme of last week's seminar was the notion of looming. The presenter, Jason Throop, discussed his experiences at the beginning of the COVID-19 epidemic.

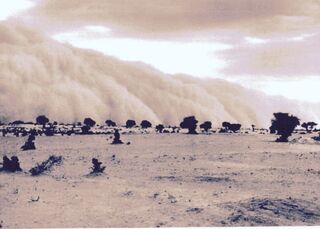

In an essay, he eloquently discusses the impact that COVID-19’s looming presence had on himself and his family. (See Throop forthcoming.) During the ensuing discussion, the participants tried to define the indeterminate fuzziness of “looming.” For me, "looming” always brings to mind the image of a gathering wave of dust that is slowly but inexorably coming to engulf me in a towering cloud that eclipses the sun.

The COVID-19 pandemic is like a series of dust waves that are crashing down upon us. These waves are choking our future. We find ourselves today in a perilously stressful state.

COVID-19 is everywhere and is going nowhere. Despite the increasingly rapid rate of highly effective vaccinations, there are new, more contagious and deadly variants of the virus that are spreading widely in Europe, North America, and South America. France is now in a one-month national lockdown.

Indeed COVID-19 fatigue is the new norm. Tired of social-distancing protocols, people are taking risks that could endanger not only themselves and their loved ones but also the complete strangers they might encounter at a restaurant, a grocery store, or an airport. And who is to say that COVID-19 is a singular phenomenon? Given the ongoing degradation of the natural world, we can probably expect another virus to jump from the bush, as they say in West Africa, to the village.

But the stressful realities of COVID-19’s robustness are only part of the picture. There is troublesome turmoil in the world. In western Niger, the remote and poor region of the world where I conducted many years of anthropological research, the countryside is overrun with violence. Islamists loot small villages and demand protection tribute from farmers, who, if they’re lucky, earn $300 a year. If the peasant farmers don’t comply, the Islamists kill them.

In May of 2020, they killed 20 people in a Western Niger village that I know. Earlier this year, they killed 100 villagers in the same region. What had been a poor place graced with gracious conviviality and beautiful ceremony is now beset with religious intolerance and the violence of hate.

Sadly, these trends are widespread. In the U.S., there is no shortage of systematic racism, ethnic discrimination, hateful violence, income inequality, and, of course, coronavirus infections, hospitalizations, and deaths—all of which creates ever-present anxiety and stress—especially if you are neither white nor Christian. If you combine these elements, which are inextricably linked, we are all standing in the path of looming waves of dust that relentlessly overwhelm us. In this troubling existential state, we are immobilized. Our lives flash before our eyes. What must we know to confront and adapt to these ever-looming waves of dust?

It is clear that our contemporary state of emergency can be traced to the longstanding culture of extraction, the fundamental tenet of which is that human beings can dominate nature and one another. Since the Industrial Revolution, human beings have extracted from nature such wonders as fossil fuels, minerals, trees, and water. In doing so, we have depleted the Earth’s natural resources and produced polluting agents that have brought on the death of forests and the degradation of rivers, oceans, coral reefs, and landscapes—all in the name of progress and capitalism.

Extraction also creates regimes of mastery, compelling states and/or individuals to exercise a "will to power" to establish and maintain social and political domination. The "will to dominate" has brought us incessant warfare, famine, disease, inequality, racism, and the aforementioned violence of hate. Even in the sciences and social sciences, we extract principles, formulas, categories, definitions, and theories from the free flow of experience, all of which provide a sense of control and certainty. We study. We know. We understand—or think we understand.

In their revolutionary and insightful book, Hyposubjects: On Becoming Human, Morton and Boyer (2021: 62) write:

Because mastery, transcendence, excess—that is the world that we know. Those are the qualities of this era. And with the refinement of excessive mastery in various localities has emerged relentless predatory impulses—monotheistic, capitalistic—to bring the world into alignment with our transcendence mission. An imploded form of subjectivity is worth considering as an antidote. One that is denser, but also more aware of the architecture of its density and of the gravitational forces that hold it together, one that is not constantly seeking the beyond.

For me, one antidote to the devastating excesses of extractive mastery is the rediscovery and recognition of indigenous wisdom. Indigenous people like the Songhay of Niger understand the relationship of bush to village. The bush is always more powerful and dangerous than the village. If the forces of the bush are not respected, they bring drought, floods, destruction, diseases like COVID-19, and death. If you attempt to master the bush, it masters you.

The same can be said for sorcery. If you “eat” sorcery, as the Songhay like to say, sorcery will “eat”—take control of—you and your life. For Songhay people, who live in harm’s way day in and day out, there is little control and no certainty. Songhay people have learned to accept their existential limits and live fully within them, which, in the end, enables them to live robustly in profoundly challenging physical, economic, and political circumstances. Like other indigenous populations, Songhay people understand that to avoid wholesale extinction—the bush totally consuming the village—there needs to be profound cultural change—more modesty, creativity, flexibility, playfulness, and respect and less certainty, mastery, and domination.

Our past has led us to the edge of extinction. If we open our ears and listen to the wisdom of indigenous elders, our future could become a truly human one.

References

Morton Timothy and Dominic Boyer 2021. Hyposubjects: On Becoming Human.. USA: Amazon.com.

Troop, Jason (Forthcoming) "Looming," Puncta: Journal of Critical Phenomenology.