Eating Disorders

Does the Brain Heal After an Eating Disorder?

It is unclear if the brain fully recovers from an eating disorder.

Posted July 25, 2022 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

- Eating disorder recovery is different for everyone, making it difficult to study.

- Brain structure and function can change during eating disorder illness. It's unclear how much of this is reversed during recovery.

- Lasting changes in the brain could interfere with long-term eating disorder recovery.

- Brain stimulation could help alter brain circuits during eating disorder treatment.

Eating disorders (EDs) can severely damage the brain and body.

Common consequences of EDs are changes in brain size and function, malnutrition, electrolyte imbalances,9 and gastrointestinal complications.10

Nonetheless, while we know that EDs can damage our brains, we don't yet know how much of this damage is permanent. This is partially due to the challenges of studying ED recovery.

Challenges of Studying Eating Disorder Recovery

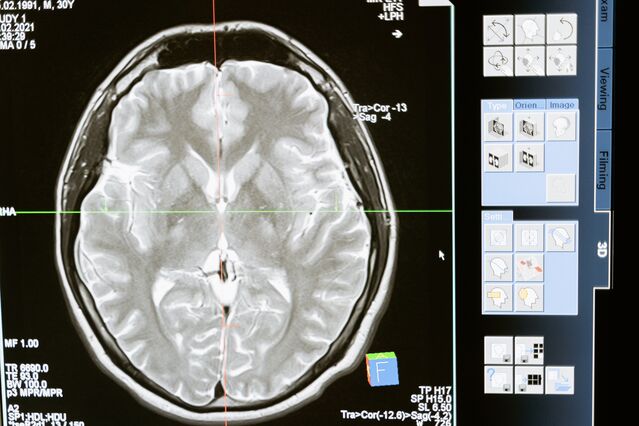

The skull presents a major obstacle when studying the brains of people recovered from EDs. Made up of 6-7 mm thick cranial bones, the skull prevents us from directly analyzing the brain without invasive surgery.

To overcome this challenge, researchers use tools like fMRI, MRI, and EEG to estimate the brain’s size, shape, and activity. These tools only allow us to make educated guesses about the brain, though, and they don’t allow us to look at specific brain proteins. This leaves us with a lot of unanswered questions about the permanency of brain damage after an ED.

Another challenge of studying the brain in ED recovery is that researchers can’t always tell if a brain abnormality was caused by an ED. Other factors, like chemicals in the environment or malnutrition, are additional, possible causes of brain abnormalities. Consequently, researchers aren't always certain that EDs cause permanent brain damage.

What Does Recovery Mean?

The ambiguity of the word “recovery” presents another challenge for studying the brain during ED recovery.11 Recovery can mean different things for different people. For medical professionals, recovery is often classified as weight restoration or reduced ED symptoms.

These medical definitions, however, overlook the psychological symptoms of an ED, which can linger long after visible symptoms disappear. If psychological symptoms, such as body dissatisfaction, persist after weight gain, can the person be considered recovered? Nuances like these make it difficult to define recovery in research.

People also disagree if recovery has an endpoint. For many, it is a lifelong process. This, again, makes it difficult to define what recovery means in a research study.

Brain Structure in Eating Disorder Recovery

Nonetheless, despite these challenges, research has shown that having an ED can change a person's brain structure.1

Brain structure refers to the brain's makeup and organization. In simple terms, the brain is composed of two different kinds of matter: white matter (e.g., axons) and grey matter (e.g., neurons). If the brain were a computer, the grey matter would be the processing part and the white matter would be the wires that send information throughout the computer.

Whole brain analyses have shown that people ill with anorexia nervosa (AN) or bulimia nervosa (BN) have less grey and white matter compared to people without AN or BN.1; 2 These structural changes likely contribute to ED maintenance and resistance to treatment.

The good news is that these structural changes can be reversed. Research has shown that, on average, 43 percent of lost grey matter is regained after 4 months of weight restoration from AN, with most white matter restored during this time.2 Brain matter increases have also been found in people recovered from BN. In this case, recovery was defined as symptom reduction (e.g., binge eating) for over 2 years.2

Additional evidence from brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) studies suggests that the brain heals during ED recovery.6 BDNF is a protein that helps neurons survive, grow, and repair, and it has been shown that people recovered from AN have higher levels of BDNF than people ill with AN. Increased BDNF during AN recovery could indicate that the brain goes through a healing process during AN recovery.6

Nonetheless, this healing process might not be so simple.

For example, studies looking at the whole brain after AN recovery show that white matter might be restructured in a way that interferes with how these individuals experience food reward.12 This means that, while the brain does heal during ED recovery, we're not certain if it's a full recovery. The brain might remain restructured.

Another thing to consider is the age of ED onset. Because adolescence is a common time for ED development, we have to question if ED symptoms during adolescence interfere with brain development. If they do, adolescent EDs could result in more permanent brain damage than EDs that start after adolescence.7

Finally, more recent brain analyses have shown us that the entire brain isn't reduced during an ED illness. Rather, parts of the brain are larger in people currently ill with and recovered from an ED compared to people without an ED.7

For example, women currently ill with or recovered from AN have increased grey matter in the orbitofrontal cortex and right insula compared to people without AN, while women currently ill with or recovered from BN have increased grey matter in the left insula. These lasting increases in grey matter could contribute to behaviors such as food avoidance or problems experiencing fullness, all of which make ED recovery more challenging.

Brain Functioning in Eating Disorder Recovery

There is also evidence that EDs change brain function.3 Brain function refers to how the brain processes information, such as memories, senses, decisions, and rewards. Using the computer analogy, brain function can be thought of as the software, while brain structure is the hardware.

Evidence has shown that repeatedly performing ED behaviors (e.g., binge eating) can change how the brain functions, and these changes can cause lasting disruptions that influence how we interact with our internal and external worlds.3; 7 For example, how much we eat (e.g., food restriction) or our meal patterns can influence how relevant and important a reward (e.g., food) is to us and how motivated we are to get it. In this way, our eating behaviors influence how we experience food.

An example of this is food sensitivity in AN. Brain research has shown that people recovered from AN are oversensitive to unexpected food tastes.4 This means that people recovered from AN experience increased pleasure from new foods.

However, this sensitivity becomes dulled with repeated tastes.4 This could mean that people recovered from AN are hypersensitive to new tastes, but work to reduce this intensity with repeated exposure to that taste. Training the brain to be less responsive to certain tastes could be a way for them to control cravings and avoid overeating. Because these changes might be permanent, they could interfere with recovery.

It has also been found that brain circuits and brain chemicals in people recovered from AN and BN are altered in a way that makes it difficult for them to distinguish between positive and negative information.5 Exactly what this means is unclear. It does, however, indicate that, even with reduced symptoms, people recovered from an ED have ongoing difficulties distinguishing pleasure from punishment. These alterations might also contribute to struggles with body dissatisfaction.

Summary

While research shows that the brain heals during ED recovery, we don't know the extent of it. A better understanding of what brain damages endure during ED recovery, however, could help develop better ED treatments. For example, brain stimulation could be one way to retrain brain circuits to pre-illness states.8 More research is needed, however, to fully grasp what we can do to heal the brain during ED recovery.

References

1) Seitz, J., Bühren, K., von Polier, G., Heussen, N., Herpertz-Dahlmann, B., & Konrad, K. (2014). Morphological changes in the brain of acutely ill and weight-recovered patients with anorexia nervosa. Zeitschrift für kinder- und jugendpsychiatrie und psychotherapie, 42, 7-18. doi: 10.1024/1422-4917/a000265.

2) Wagner, A., Greer, P., Bailer, U., Frank, G., Henry, S., Putman, K.,…& Kaye, W. (2006). Normal brain tissue volumes after long-term recovery from anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Biological Psychiatry, 59, 291-293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.06.014.

3) Frank, G., Shott, M., Stoddard, J., Swindle, S., & Pryor, T. (2021). Association of brain reward response with body mass index and ventral striatal-hypothalamic circuitry among young women with eating disorders. JAMA Psychiatry, 78, 1123-1133. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.1580.

4) Frank, G. (2013). Altered brain reward circuits in eating disorders: Chicken or egg? Current Psychiatry Reports, 15.

5) Wagner, A., Aizenstein, H., Venkatraman, V., Bischoff-Grethe, A., Fudge, J., May, J.,…& Kaye, W. (2010). Altered striatal response to reward in bulimia nervosa after recovery. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 43, 289-294.

6) Ehrlich, S., Salbach-Andrae, H., Eckart, S., Merle, J., Burghardt, R., Pfeiffer, E.,…& Hellweg, R. (2009). Serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor and peripheral indicators of the serotonin system in underweight and weight-recovered adolescent girls and women with anorexia nervosa. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience, 34, 323-329.

7) Frank, G. (2015). Advances from neuroimaging studies in eating disorders. CNS Spectrums, 20, 391-400.

8) Duriez, P., Khalil, R., Chamoun, Y., Maatoug, R., Strumila, R., Seneque, M.,…& Guillaume, S. (2020). Brain stimulation in eating disorders: State of the art and future perspectives. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9.

9) Greenfeld, D., Mickley, D., Quinlan, D., & Roloff, P. (1995). Hypokalemia in outpatients with eating disorders. Journal of Psychiatry, 152, 60-63. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.152.1.60.

10) Sato, Y., & Fukudo, S. (2015). Gastrointestinal symptoms and disorders in patients with eating disorders. Clinical Journal of Gastroenterology, 8, 255-263.

11) Bardone-Cone, A., Hunt, R., & Watson, H. (2018). An Overview of Conceptualizations of Eating Disorder Recovery,

Recent Findings, and Future Directions. Current Psychiatry Reports, 20.

12) Shott, M., Pryor, T., Yang, T., & Frank, G. (2016). Greater insula white matter fiber connectivity in women recovered from anorexia nervosa. Neuropsychopharmacology, 41, 498-507.