Body Image

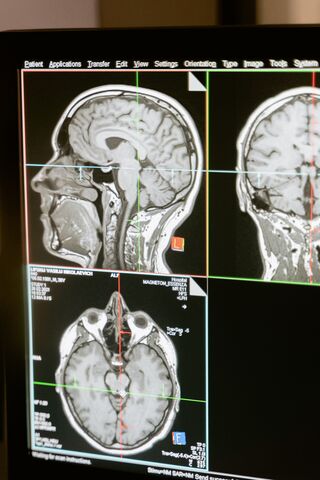

Body Image and the Brain

The central nervous system plays a key role in body image development.

Posted March 2, 2022 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- Body image develops in the central nervous system.

- Body image has perceptual, affective, and cognitive components.

- Individuals with eating disorders may have atypical functioning in brain areas involved in body image.

Despite advances in our understanding of eating disorders, many people still perceive these illnesses as vain lifestyle choices.

There are, however, many neurological components involved in how we perceive, feel towards, and think about our bodies. And, atypical functioning in these components can, therefore, result in body distortions that are very real (and very distressing) for some people.

What Is Body Image?

Though seemingly straightforward, body image (i.e., how we perceive and feel toward our body) is a complex concept involving aspects of cognition, affect, perception, and behavior.1

Exactly how body image develops remains unclear, but biogenetic structuralism theory can provide some clarity. Biogenetic structuralism suggests that body image perceptions develop in congruence with the central nervous system (CNS). Therefore, it is the organization of the CNS that determines the mental representations, or cognized environments, we create for ourselves and our surroundings.2

Cognized environments (e.g., body image) are shaped by a variety of internal (e.g., bodily sensations) and external (e.g., culture) factors, and they don’t necessarily reflect reality. This means that our mental representations of our bodies can be made up of inaccurate body size and shape estimates.

For most people, body perceptions are fluid and updated frequently. Throughout the day we gather new, first person-oriented (e.g., egocentric) information about our bodies and store it in our short-term memory.7

These daily notes, however, aren't what we think of when we are asked to describe our bodies.

Rather, when we think about our bodies, we draw on a more enduring construct, which we see in the third person (e.g., objectified). This objectified viewpoint is known as the allocentric perspective and it's stored in our autobiographical, long-term memory. To keep this mental representation up to date, we use the new information we gather about our bodies from the egocentric perspective.7

Allocentric Lock Theory

The brains of people with body image illnesses, however, might skip a step in this process.

According to allocentric lock theory, people with an eating disorder are unable to store new information about their bodies in their short-term memory. This means that their mental representations aren't updated and they continue to rely on outdated perceptions of themselves, despite possible changes (i.e., weight loss).

This explains why some individuals with an eating disorder find it difficult to accurately describe their current bodies.

Allocentric lock theory can also help explain eating disorder behaviors (i.e., excessive exercise), which could be especially useful for caregivers of those with an eating disorder. Watching someone engage in certain behaviors that aren't necessarily good for them can be confusing and frustrating. However, if we know that the individual might be relying on an outdated or distorted body image concept for self-reference, their behaviors make a lot more sense.

What Parts of the Brain Are Involved in Body Image?

Distinct brain networks manage different body image components, such as perception.

The perceptive aspect of body image refers to our accuracy when estimating body size and shape. It likely utilizes brain regions with specialization for body representation, such as the extrastriate body area (EBA) and the fusiform body area (FBA). Atypical functioning in these areas has been found in people with anorexia nervosa (AN), which could explain the difficulties these individuals have with accurately estimating their body size and shape.

Similarly, atypical functioning in the parietal cortex (i.e., an area involved in sensory integration, body awareness, and visual information) plays a role in body image and eating disorder development.

In addition to perception, additional body image components include affect (i.e., how we feel towards our body shape and appearance) and cognition (i.e., our beliefs about our conceptualized bodies). These components likely utilize brain areas involved in information integration, such as the insula.5

The insula, which is thought to function atypically in those with eating disorders, serves as a hub for integrating information (i.e., body sensations, emotion, and cognition) from several different brain regions. Using this information, the insula creates our sense of “self." This includes how we think about and feel towards our bodies.

Beyond Eating Disorders

Most eating disorders involve symptoms where individuals are concerned with their body weight and shape. Body dysmorphia disorder (BDD), however, is slightly different, despite this illness also involving appearance concerns. Rather than general body-weight concerns, BDD symptoms include individuals fixating on specific areas of their appearance (e.g., the nose).9

Nonetheless, despite these symptom variations, it has been demonstrated that the visual cortexes (i.e., involved in visual information) of those with BDD or AN function similarly.8 This suggests that atypical functioning in the visual cortex might interfere with individuals’ general abilities to accurately assess their bodies, regardless of illness specificity.

Additionally, recent studies with patients who have developed primary brain tumors3 or who have acquired brain injuries4 have shown that these injuries can result in clinically significant levels of body dissatisfaction. This further verifies the role of the brain in body image.

Body Image and the Senses

Because body image supposedly develops in the CNS, all of our senses, not just vision, influence our body conceptions.6 For example, a recent study found that certain odors, such as vanilla, are associated with thick silhouettes and “feeling heavier," while lemon is associated with thin silhouettes and “feeling lighter." Additionally, higher-pitched sounds enhance feelings of “lightness,” while lower-pitched sounds enhance feelings of “heaviness.” These findings have not been looked at with regards to eating disorders, though.

Conclusions

Despite advances in eating disorder education, many people still perceive these illnesses as self-inflicted.10 These misconceptions are problematic because they reduce compassion for those with eating disorders, discourage support for policy change (i.e., increases in treatment accessibility), and limit research funding.

Developing an understanding of the biological underpinnings of body image and its role in eating disorder development can (hopefully) reduce some of these stigmas and increase compassion and assistance for those with an eating disorder.

References

1. Esposito, R., Cieri, F., di Giannantonio, M., & Tartaro, A. (2018). The role of body image and self-perception in anorexia nervosa: The neuroimaging perspective. Journal of Neuropsychology, 12, 41-52.

2. Laughlin, C. (1997). Body, brain, and behavior: The neuroanthropology of the body image. Anthropology of Consciousness, 8, 49-68.

3. Rowe, L., et al. (2020). The prevalence of altered body image in patients with primary tumors: AN understudied population. Journal of Neuro-onocology, 147, 397-404.

4. Corallo, F. (2021). The relationship between body image and emotional and cognitive impairment after brain damage: A preliminary study. Brain and Behavior, 11.

5. Badoud, D., & Tsakiris, M. (2017). From the body’s viscera to the body’s image: Is there a link between interoception and body image concerns? Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 77, 237-246.

6. Brianza, G., et al. (2019). As light as your scent: Effects of smell and sound on body image perception. IFIP Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, 179-202.

7. Lander, R., et al. (2019). Executive functioning and spatial processing in anorexia nervosa: An experimental study and its significance for the allocentric lock theory. Eating and Weight Disorders – Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 25, 1039-1047.

8. Moody, T., et al. (2021). Brain activation and connectivity in anorexia nervosa and body dysmorphic disorder when viewing bodies: Relationships to clinical symptoms and perception of appearance. Brain Imaging and Behavior, 15, 1235-1252.

9. Body Dysmorphic Disorder Foundation, retrieved from: https://bddfoundation.org/information/bdd-related-conditions/eating-dis…

10. Crisp, A. Stigmatization of and discrimination against people with eating disorders including a report of two nationwide surveys. European Eating Disorders Review, 13, 147-152.