Psychiatry

Could Methylene Blue Help Treat Depression?

Why a blue dye may be a viable treatment for psychiatric disorders.

Updated July 20, 2024 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Key points

- Methylene blue is both a dye and a medicine.

- Methylene blue has been demonstrated to improve depression, as well as anxiety and Alzheimer's disease.

- Methylene blue also enhances memory.

Methylene blue is both a dye and an FDA-approved medication. Described as the first fully synthetic drug used in medicine, methylene blue was initially synthesized by a German chemist in 1876, and 15 years later, it was employed as a treatment for malaria. This dye/medicine continued to play an important role as an antimalarial medication during the First and Second World Wars. In the late 19th century, methylene blue was explored as a treatment for schizophrenia, and later, it was employed as a treatment for urinary tract infections, an antidote for carbon monoxide and cyanide poisoning, and a drug for septic shock. Today, this amazing medicant is being explored as a treatment for neuropsychiatric conditions.

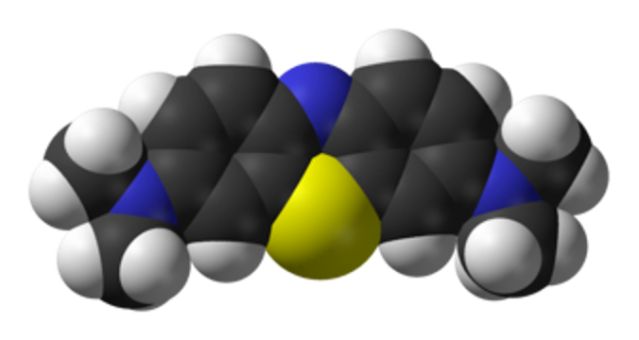

The chemical structure of methylene blue is similar to that of both tricyclic antidepressants and the anti-seizure medicine carbamazepine. However it’s mechanisms of action are quite different from these medications. Some of these mechanisms are dose dependent, meaning that higher doses can have the opposite effects of lower doses. The specific mechanisms of methylene blue include antibacterial, antiviral, and anti-inflammatory effects; blockade of GABA-A receptors; inhibition of monoamine oxidase A (MAO-A); improvement in mitochondrial functioning; and inhibition of tau protein aggregation.

Methylene blue also affects the transmission of the primary excitatory neurotransmitter in the human brain, glutamate, by inhibiting N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors. This results in an increase in brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). In this way, methylene blue functions similarly to ketamine and other psychoplastogens such as psilocybin and LSD, but it does not cause alterations in consciousness, such as those produced by psychedelic medicines.

Antidepressant effects

Since the 1970’s, methylene blue has been found to be an effective antidepressant medicine in multiple studies. For example, a 1986 study performed by researchers in Scotland explored the effects of 15 mg of methylene blue administered daily to 13 women who suffered from severe depression. Their response was compared to 15 women who were given a placebo. The women who received a placebo did not improve, but those who were given methylene blue showed marked improvement. In fact, within one week, the women who were receiving methylene blue showed a statistically significant improvement in their depressive symptoms relative to those in the placebo group.

In another study, 24 chronically and/or severely depressed participants were treated with methylene blue 200 mg or 300 mg daily. Nineteen of these individuals were diagnosed with bipolar disorder, and 14 of these showed “definite improvement.”

In 1986, a two-year randomized, cross-over study examined the effects of 300 mg versus 15 mg of methylene blue daily in 17 individuals with bipolar disorder. All participants also took lithium throughout the study. The investigators found that individuals who took the higher dose were significantly less depressed than those who took the lower dose, and no change in manic symptoms occurred in either group. Hospitalization rates were reduced following treatment with either dose.

Another study involved a double-blind crossover design with men or women who were diagnosed with bipolar I or bipolar II disorder and were partially stabilized on lamotrigine. Participants were randomly assigned to receive either methylene blue at a dose of 15 mg or 195 mg daily for three months, then they were switched to the other dose. They continued to take lamotrigine throughout the study. Twenty-seven individuals completed the study. Methylene blue was well tolerated, and no severe side effects were reported. None of the individuals experienced a worsening of manic symptoms. However, there was an overall reduction in symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Methylene blue as a treatment for other psychiatric disorders

In 1938, a study described the use of methylene blue as a treatment for schizophrenia. More than 50 years later, another study explored the use of methylene blue in eight patients with schizophrenia who failed to respond to conventional antipsychotic medications. These individuals demonstrated statistically significant improvement following treatment with methylene blue, and their symptoms worsened when the medicine was discontinued.

A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled Phase II trial involving 321 individuals with mild or moderately severe Alzheimer’s disease found moderate improvement following the administration of 138 mg of methylene blue daily after 24 weeks, but higher (228 mg) and lower (69 mg) doses were ineffective.

Methylene blue has also been found to enhance memory and exert neuroprotective effects.

Side effects with this medicine, which are typically mild and well tolerated, may include blue-colored urine, nausea, and headache.

Summary

While newer antidepressant medications often cost hundreds of dollars per month, older therapeutics that can no longer be patented may provide effective and more affordable options for people suffering from psychiatric illnesses who cannot afford more expensive treatments. Methylene blue is one such medicine. Further studies will help us understand more about the potential benefits of this unique therapeutic, as well as its benefits for the treatment of psychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders.

References

Alda, M., 2019. Methylene blue in the treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders. CNS drugs, 33(8), pp.719-725.

Rojas, J.C., Bruchey, A.K. and Gonzalez-Lima, F., 2012. Neurometabolic mechanisms for memory enhancement and neuroprotection of methylene blue. Progress in neurobiology, 96(1), pp.32-45.

Wischik, C.M., Staff, R.T., Wischik, D.J., Bentham, P., Murray, A.D., Storey, J., Kook, K.A. and Harrington, C.R., 2015. Tau aggregation inhibitor therapy: an exploratory phase 2 study in mild or moderate Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 44(2), pp.705-720.