Neuroscience

Are Our Leaders Using Only Half Their Brains?

Brain imaging reveals that you can’t use all your brain at once.

Posted January 27, 2019

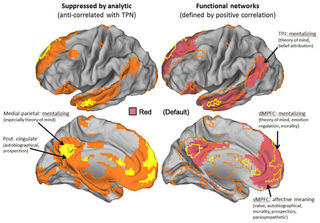

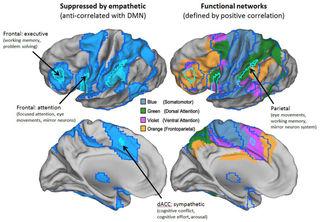

In previous posts, I have reported one of the biggest and most surprising discoveries in neuroscience: that of “anti-correlated” (that is, mutually inhibiting) brain networks (see figures):

Recent research in neuroscience suggests that the division between task-oriented and socio-emotional-oriented roles derives from a fundamental feature of our neurobiology: an antagonistic relationship between two large-scale cortical networks—the task-positive network (TPN) and the default mode network (DMN). Neural activity in TPN tends to inhibit activity in the DMN, and vice versa. The TPN is important for problem solving, focusing of attention, making decisions, and control of action. The DMN plays a central role in emotional self-awareness, social cognition, and ethical decision making. It is also strongly linked to creativity and openness to new ideas. Because activation of the TPN tends to suppress activity in the DMN, an over-emphasis on task-oriented leadership may prove deleterious to social and emotional aspects of leadership. Similarly, an overemphasis on the DMN would result in difficulty focusing attention, making decisions, and solving known problems.

The task-positive network (TPN). The TPN representation based on anti-correlations corresponds to multiple networks defined by positive correlations. Left panels show just the TPN derived from anti-correlations in blue.Source: Front Hum Neurosci. 2014; 8: 114.

As I have also argued in previous posts, the TPN/DMN distinction maps onto the mentalistic/mechanistic one of the diametric model of cognition, with the TPN being the network for mechanistic, bottom-up, focused, devil-in-the-detail thinking, and the DMN being that devoted to mentalistic, top-down, social skills and group-think. As one of the authors has put it, the anti-correlation between the TPN and DMN “reflects a powerful human tendency to differentiate between conscious persons and inanimate objects in both our attitudes and modes of interaction.”

Indeed, if you think about it, we live in two completely different worlds. There is the tangible, physical universe of objects, ruled by the laws of physics. But there is also an intangible, imaginary universe of ideas, concepts and feelings which obeys completely different rules. In the physical universe, you have to be in one place at a time and you cannot travel instantaneously to another. In the parallel universe of the mind, however, you can think of yourself being here and there at the same time, and you can transport yourself anywhere instantly. In the universe ruled by physical laws, time only runs forwards, and at a constant rate, and people age and die. But in the universe of thought you can rewind the tape and recall your past, or fast-forward into the future, and picture what might happen. Not so the physical universe: there you have to accept what has happened as irrevocable, and have to wait patiently for whatever is to come. The objective universe is fatalistic in this respect, but the mental one allows freedom, opportunity, and multiple outcomes. In the world of the mind we are literally fancy-free, with infinite powers, possibilities, and potential. But in the world of tangible reality we are prisoners of fate, where physical causality rules and conservation laws dictate that we cannot have it both ways at once. No wonder we have evolved an anti-correlated brain system for each!

In the paper which I quote above the authors review major theory and research on leadership roles in the context of these recent findings from neuroscience and psychology. Their focus is on business leadership, but this outstanding paper prompts me to raise a worrying issue on which I have touched once or twice before.

Today most of us are fortunate to live in democracies whose leaders have to get themselves elected rather than being imposed on us by force. Obviously, excellent mentalistic skills are required of leaders in such a situation, which implies that these leaders’ DMNs are kept busy and their thinking in mentalistic mode most of the time—particularly if you could describe mentalism as the art of getting on with people and the DMN as its dedicated brain system. If you could scan the brains of the great and good at Davos, my guess is that their DMNs would be shining brightly!

But if so their TPNs would be off-line (except perhaps to order the next drink). Worse still, Davos-like ambiences are ideal for what I termed psychotic savants: individuals with hyper-mentalistic social, political, and mind-reading skills such as Bruno Bettelheim or Trofim Lysenko. And obviously, leadership is another such skill with which such psychotic savants are gifted, as the careers of both Lysenko and Bettelheim demonstrate all too disastrously. Indeed, a bitter experience of my own recounted in a previous post reveals, it does not take much to get groups of otherwise intelligent people to switch to mentalistic mode, turn off their TPNs, and begin acquiescing to nonsense.

Does this partly explain the current shambles British leaders have got themselves into over Brexit, the equally shambolic American presidency, and the French president's problems? To my way of thinking, it certainly explains the decision taken by a previous British government to promote diesels as “clean”—one that is now thankfully being rescinded and, given the reputation of diesels, was always surprising to anyone with an ability to think mechanistically about them.

A main reason that the disastrous diesel policy was put in place was that it was motivated by climate concerns, which have certainly come to dominate the “ethical decision making” of our leaders, not to mention their “creativity” and “openness to new ideas” where policy is concerned. The trouble with both creativity and new ideas is that they can be at best quirky and at worst lunatic unless they are subjected to a little criticism. But there is an increasingly long list of items which in today’s world cannot be criticized or questioned without inviting DMN-igniting charges of “X denial/phobia”, with anthropogenic global warming being only one Xample (if you will excuse the pun-in-print).

If these DMN-dominant issues dominate our leaders’ concerns as they seem to do, there is a serious problem with decision making at the top which perhaps explains why increasingly people at the bottom are becoming restive—perhaps because they, by contrast, have their TPNs actively engaged in trying to cope with the mounting problems of everyday life which their leaders are imposing on them.

References

Boyatzis, R., K. Rochford and A. Jack (2014). "Antagonistic neural networks underlying differentiated leadership roles." Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 8: 114.