Autism

A New Test of the Diametric Model Using Visual Perception

Autism is visually bottom-up and atomistic, psychosis top-down and holistic.

Posted June 2, 2018

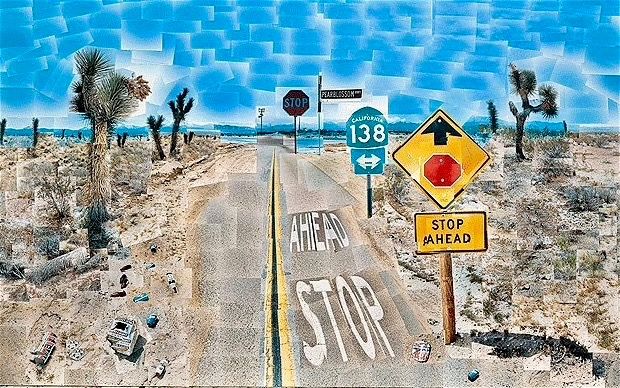

According to the diametric model of the mind and of mental illness, genius is the rare, harmonious combination of both autistic and psychotic cognition in some unusual and/or original way. David Hockney’s Pearblossom Highway illustrated above is a paradigmatic example.

At first sight, it seems to be a simple scene exemplifying classical, linear perspective, with the viewer’s line of sight following the road to the horizon and converging on the vanishing point there. But closer inspection shows it to be made up of a myriad of polaroid images, every single one of which was taken individually from a different view-point. This means that each polaroid has its own, unique perspective and vanishing-point (Hockney stood on a ladder to get the image of the big STOP sign, and the litter in the foreground was taken close-up from above).

This portrays the scene much more realistically than a single photograph of it would have done because our eyes are not photographic cameras, and we do not see by standing stock still and taking one, unique exposure of a scene, which is then fixed in our brains like a polaroid print. On the contrary, we and our eyes are constantly in movement and continually add together multiple, slightly differently-seen images of the same scene, just as Hockney’s montage does.

The picture blends insights from both ends of the continuum: the mechanistic one of photography in this case with the mentalistic one of the overall composition and conception of the scene: bottom-up, atomistic detail with top-down, holistic vision in one stunning image. Indeed, you could see the bottom-up, detailed polaroids as representing the autistic, hypo-mechanistic mindset, and the top-down, overall composition the opposite, hyper-mentalistic, psychotic one, but balanced here in a work of visual genius.

But would such a characterization be true? A new study by Ahmad Abu-Akel and colleagues provides experimental evidence that it is. As these authors point out, our capacity to attend to a target while ignoring irrelevant distraction affects our ability to successfully interpret what we see. Previous reports have sometimes identified excessive distractor interference in both autism spectrum disorders (ASD) and schizophrenia spectrum disorders (SSD) and in neurotypical individuals with high subclinical expressions of these conditions. Independent of task, the researchers show that the direction of the effect of autism or psychosis traits on the suppression or rejection of a non-target item is diametrically opposite in the way I suggested above. As the authors explain:

The present study thus has two main aims. First, it examines whether autism and psychosis traits will be beneficial or detrimental depending on the task demand, and (2) whether autism versus psychosis traits would, regardless of the task (context), induce contrasting, diametric effects on target selection in the presence of a non-target, salient distractor. To this end, we conducted two separate studies in neurotypical individuals in whom autism and psychosis traits were assessed in tandem. We test our hypotheses in neurotypical individuals based on the notion that both autism and psychosis traits exist on a continuum, ranging from typicality to disorder. This approach has the advantage of eliminating the confounding effects of duration of illness, active symptomatology or medication.

In Study 1, participants performed an adapted version of the morphed face-discrimination task (above). In this task, which required participants to actively ignore or suppress an irrelevant scene, the authors estimated contrast threshold of the distractor scene at which the participant was still able to correctly identify the face. They predicted that, in contrast to psychosis traits, increasing autism traits would be beneficial to performance, i.e., withstanding a greater level of distraction while still correctly identifying the face. In terms of Hockney’s picture, this equates to concentrating on the individual polaroids, while ignoring the whole: e.g., noticing the Devil-in-the-detail litter or the road signs.

In Study 2, and unlike the morphed face-discrimination task, the influence of a salient non-target item in a visual search task was expected to improve performance. There is evidence that under conditions similar to the visual search task, higher levels of autism traits are associated with poorer performance and the experimenters hypothesize that higher autism traits would be associated with worse performance in this task, whilst higher psychosis traits would be associated with better performance.

Thus, regardless of the direction of the effect in each task, the authors predicted opposite effects on performance of the two trait dimensions. If confirmed, this would constitute the most stringent test, to date, of the diametric model in a neurotypical population. In Study 1, in which the presence of a salient non-target item hindered performance, higher autism traits were indeed associated with better performance, while higher psychosis traits were associated with worse performance. In Study 2, in which the presence of a salient non-target item facilitated performance, a complete reversal of effects was observed (Fig 2 below).

The authors conclude that

our results confirm that ASD and SSD expressions have diametric effects on distractor suppression, and dependent on the context in which the stimulus is presented, the expressions of these conditions can be associated with performance advantages. Moreover, as can be inferred from the bias score analysis (Fig. 2), attentional control in ASD and SSD might be better explained by considering the relative, rather than the absolute, expression of the symptoms of these conditions within the individual. The latter point behoves a shift in both research and clinical practice where ASD and SSD symptom expressions ought to be assessed simultaneously, particularly in light of the unique diametric effects these conditions appear to have on brain and behavioral outcome measures. This would be an important step forward if we were serious about the need to build multidimensional models of psychopathology.

I could not agree more.

(With thanks and acknowledgement to Ahmad Abu-Akel for bringing this to my attention.)