Adolescence

Margaret Mead and the Great Samoan Nurture Hoax

An iconic account of adolescence is pure social science fiction.

Posted February 7, 2017

The post to which this is an addition got an astonishingly large amount of attention, and was briefly number one in Psychology Today's online hit parade. I suspect that it may be because it gave the lie to popular urban myths about nature/nurture and sex/gender.

As I pointed out in a previous post, the nature/nurture controversy has been an acrimonious one, and nowhere more so than over this issue. Furthermore, as I also noted in passing there, Margaret Mead has a lot to answer for.

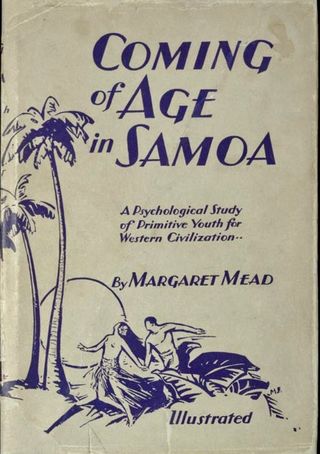

Margaret Mead’s Coming of Age in Samoa purported to provide ethnographic proof that nurture was the dominant factor in child development and adolescence. Subtitled A Psychological Study of Primitive Youth for Western Civilization, Mead’s book was widely read, in part perhaps because it is written, according to one commentator, “in ridiculously heightened prose, more like a Cosmopolitan article than an essay.” According to a recent account:

Coming of Age in Samoa was a sensation—not an overnight one, but it crept up on and conquered American hearts... A lot of Americans read it as a straightforward utopia, encouraged in doing so by a long tradition of viewing Polynesian islanders as happy, uncomplicated, semi-naked sensualists, as well as by William Morrow’s dust-jacket depicting Polynesian lovers holding hands under a palm tree (left), and by Mead’s unusually lyrical prose. Some anthropologists read it the same way, disapprovingly. E. E. Evans-Pritchard spoke dismissively of the new “wind-rustling-in-the-palm-trees” school of anthropology. His older colleague, A. C. Haddon grumbled at the substitution of the “lady novelist” for the professional ethnographer.

Mead portrayed the Samoans as “one of the most amiable, least contentious, and most peaceful peoples in the world,” adding that “In Samoa love between the sexes is a light and pleasant dance,” and that male sexuality “is never defined as aggressiveness that must be curbed.” Indeed, she claimed that “the idea of forceful rape or of any sexual act to which both participants do not give themselves freely is completely foreign to the Samoan mind,” remarking that young girls had “as many years of casual love-making as possible.”

Then in the 1960s, another anthropologist, Derek Freeman, “went to Samoa a ‘fervent believer’ in the ethnography of Coming of Age as well as in the ideology of cultural anthropology.” But what he actually discovered was that, far from Samoans being among the most peaceable people in the world, serious assault in mid-1960s Western Samoa was 67 percent higher than in the USA, 494 percent higher than in Australia, and 847 percent higher than in New Zealand, while common assault was 500 percent that of the USA.

Contrary to Mead’s claims, Freeman reports that rape convictions in 1960s Samoa were twice the level of those in the USA and twenty times those of the UK. Indeed, at the time Mead was in Samoa, rape was the third most common criminal offense (partly thanks to the fact that, at odds with Mead’s portrayal of Samoa as an egalitarian, non-competitive society, men who successfully deflowered girls of superior social status could force them to marry them).

Whereas Mead claimed that Samoa was permissive about adolescent sex, there was in fact a cult of virginity; where Mead described adultery as “not regarded as very serious” by Samoans, Freeman reports that adultery was punished by death before colonization and by heavy fines afterwards; and that contrary to her portrayal of it, the pattern of adolescent crime was much the same there as anywhere else.

On the basis of a few dozen interviews with 25 adolescent girls carried out in the back room of a US Navy dispensary—there is no evidence she ever interviewed a boy—and a few touristic excursions around the islands, Mead purported to give an authoritative account of a complete culture, which she described as "a precious permanent possession of mankind… Forever true because no truer picture could be made," adding portentously, "true to the state of human behavior as it was in the mid 1920s; true to our hopes and fears for the future of the world."

Eventually, Freeman obtained a sworn confession from one of Mead’s informants and proved that, as I for one had always suspected, it was all too good to be true. Margaret Mead had been told what she wanted to hear by her less than trustworthy Samoan informants, who were embarrassed by her leading questions about topics never normally mentioned by young girls—least of all to important American ladies. He devastatingly demonstrated that Margaret Mead had not written an ethnographic account, but had published a work of social science fiction, albeit one that became enormously influential in modern American culture:

We are dealing … with one of the most remarkable events in the intellectual history of the 20th century. Margaret Mead, the historical evidence demonstrates, was comprehensively hoaxed by her Samoan informants, and then, in her turn by convincing … others of the “genuineness” of her account of Samoa, she unwittingly misinformed and misled the entire anthropological establishment.

As I argued in the parallel case of Freud, this work of anthropological or psychological “science” had more to do with fiction than fact, readily explaining why it was so widely read and so credulously believed, and perhaps also explaining why posts giving the lie to it attract so much attention at Psychology Today.

References

Caton, H., ed. The Samoa Reader. 1990, University Press of America: Lahnham.

Mandler, P., "Return from the Natives," in How Margaret Mead Won the Second World War and Lost the Cold War. 2013, Yale University Press: New Haven and London.

Freeman, D. (1983). Margaret Mead and Samoa: The Making and Unmaking of an Anthropological Myth. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Freeman, D. (1998). The fateful hoaxing of Margaret Mead : a historical analysis of her Samoan researches. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press.