Attachment

Traces of Ourselves: The Remarkable Power of Touch

Throughout the life cycle, most humans crave another's touch.

Posted April 25, 2020 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

We all know the story of avaricious King Midas, who asked that everything he touched to be turned to gold. Ovid recounts the myth in Book XI of his Metamorphoses, but perhaps the most compelling version is that from American author Nathaniel Hawthorne in his A Wonder-Book for Girls and Boys (1851): King Midas has a precious young daughter, aptly named Marygold. “The more he loved his daughter, the more did he desire and seek for wealth.” A mysterious stranger appears and grants King Midas his wish. At first, Midas is enthralled and does not seem to mind he cannot see out of his golden spectacles that have turned opaque and cannot eat the sumptuous breakfast put before him. Only when Midas bends down to comfort and kiss his daughter, who has turned into a golden statue and a “human child no longer,” does he fully appreciate the foolishness of his wish. Hawthorne’s story ends happily, and we find Midas, years later, sharing his saga with Marygold’s children.

The power of touch is indeed complex.

Physician and author Lewis Thomas wrote in his essay Vibes, “We leave traces of ourselves wherever we go or on whatever we touch.” (The Lives of a Cell: Notes of a Biology Watcher, 1974, p. 35, Kindle Edition.) The word touch pervades our language: not only is there the Midas touch, but a magic touch, woman’s touch, finishing touch, common touch, nice touch, lose touch, keep in touch, out of touch, be in touch, touch and go, touch up, touched, touchstone, and touch down, among many other examples. In this time of the recommendation to shelter in place and maintain social distance amidst fears of the COVID-19 contagion, there are not only heartbreaking images of family members separated from each other but also orders to avoid simple handshakes and any form of human touch. What do we know of the human need for touch?

Touch has been described as “one of the most provocative yet least understood” of our nonverbal forms of communication, particularly because it is “open to multiple interpretations” that can include affection and intimacy but also dominance, power, and aggression. (Burgoon et al, Human Communication Research, 1992.) Skin is a “social organ,” and as such, touch becomes a “channel for social information,” with its many dimensions. (Morrison et al, Experimental Brain Research, 2010.) Touch can vary in its action (rubbing, stroking, patting, pinching) as well as its intensity, location, frequency, and duration. (Hertenstein et al, Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs, 2006). Touch can be welcome or unwelcome and can have an “intricate relationship” with culture, gender, and context. (Morrison et al, 2010; Cascio et al, Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 2018.) Further, touch is difficult to study because of its "inherent complexity," including methodological issues (much tactile interaction occurs in private and not accessible to researchers) (Hertenstein et al, 2006).

Touch also enables us to sense the external environment, as well as has a role in shaping mental representations of our own body. (Bremner and Spence, Advances in Child Development and Behavior, 2017.) About 20 percent of people who suffer the devastating loss of a limb, particularly a hand, abandon their prostheses not only because of lack of comfort and aesthetics but also because of an inability to experience tactile sensation. (Nghiem et al, Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 2015.) While prostheses now can enable considerable motor dexterity, their inability to provide amputees with sensations “remains an unsolved problem” (Bumbasirevic et al, Injury, 2009) and “the key limitation” to reestablish “full functionality of a natural limb” (Nghiem et al, 2015).

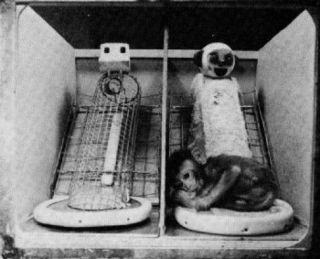

One of the first researchers to study touch systematically was Harry Harlow back in the 1950s. (Harlow, American Psychologist, 1958.) Harlow removed baby rhesus monkeys from their mothers and randomly assigned them to surrogates—the famous terrycloth "monkeys" and the metal wire "monkeys." His infant monkeys preferred the soft terrycloth surrogate whether there was food or no food, and only accepted the wire monkey surrogate when there was food. And when a "frightening stimulus" was brought into the cage, the monkeys ran to the cloth surrogate. (Gallace and Spence, Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 2010.)

Harlow's experiments were later sharply criticized, even by his former students, for "crossing ethical lines" and their overt cruelty. (Blum, Love at Goon Park: Harry Harlow and the Science of Affection, 2011 Kindle edition.) For example, Harlow called it his "pit of despair" in which he kept his monkeys, who became severely psychologically disturbed, in total isolation for years at a time. Animal rights activists described him as "the man who tortured animals," and his work ultimately led to animal rights reform.

Deborah Blum, who gives a balanced view of Harlow, notes that when Harlow started his work, no one appreciated the importance of touch and the human need not just to be loved but to "feel loved." She describes Harlow as an "impossible genius," (Introduction to 2011 edition), who could be "sarcastic, provocative, and seemingly misogynistic" (including "infuriating" some in the "fledgling" women's movement) but feels that some of the criticism aimed at Harlow reflects "revisionist history." Further, Blum notes that his work had far-reaching extrapolations to our understanding of child abuse and neglect and the dangers of destructive, rejecting mothers.

Later, other researchers focused on social grooming (allogrooming or the grooming of others) among primates and found that it has a particular role in social bonding and seems to be “all about physical touch.”(Dunbar, Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 2010.) Some primates spend 17 to 20 percent of their time, far more than to keep fur clean, in this social grooming, including rhythmic plucking, pinching, and pulling at skin debris, blemishes, and parasites of their partners. Whereas self-grooming seems to be about hygiene, social grooming, which is “far from random” and involves partnerships that are stable over time, seems more to do with relationships and affection. (Dunbar, 2010; Vallbo et al, Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology, 2007.)

Studies with human infants have also emphasized the importance of physical contact and touch for normal development, including physiological, emotional, and cognitive, particularly because infants are “exceptionally helpless” and the “least developed” of primates for such an extended period. (Barry, Infant Behavior and Development, 2019.) For example, researchers Klaus and Kennel, in the 1970s, wrote of the importance of mother-infant bonding, actual skin-to-skin contact, in the minutes just after birth, and were instrumental in changing hospital practices around the country to accommodate bonding practices. Their work, though, later met with criticism of their methodology and the strength of their data. (Hertenstein et al, 2006.) The practice of “kangaroo care,” skin-to-skin contact with the mother, though, is recommended for premature (low-weight) babies without respiratory distress, infection, or major anomalies to foster weight gain, improve breastfeeding efforts, and enhance oxygenation, though unfortunately practiced in only 57 percent of U.S. neonatal intensive care units. (Evereklian and Posmontier, Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 2017.)

One of the reasons that humans respond to touch is that touch releases hormones, including oxytocin—the cuddle hormone—and the endogenous opioids (endorphins) that can reduce stress, lower blood pressure, and even decrease pain. (Dunbar, 2010; Gallace and Spence, 2010; Bartz et al, Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 2011.) But while oxytocin, for example, can lead to trusting behavior, generosity, and cooperation, researchers emphasize that both individual and situational differences may play a role and lead to variable effects. (Bartz et al, 2011) While many people experience what has been described as touch hunger—longing for human touch (Field, Touch, p. 1, 2014) some with autistic spectrum disorder exhibit an acute pathological sensitivity to touch and resist being touched (Gallace and Spence, 2010).

Bottom line: For almost all, human touch remains essential throughout our lives, from infancy into old age. Touch releases endorphins and oxytocin, hormones that decrease stress and even pain. We do not yet know the long-term ramifications of the recommendations to maintain social distancing and avoid even handshakes in this stressful time of COVID19. Likely, though, more people will experience that powerful hunger for human touch, particularly because, as Lewis Thomas wrote, "We leave traces of ourselves...on whatever we touch."

Facebook image: GaudiLab/Shutterstock