Freudian Psychology

Collecting: A Demonic Passion

Understanding the questing spirit of the collector.

Posted December 19, 2022

Key points

- The accumulator, rationalizing that someday things will come in handy, amasses an assortment of objects without any discernment.

- The collector, different from the accumulator and the hoarder, engages in a voluntary activity of selecting and ordering.

- People can collect objects, but also ideas and experiences.

- Collecting may include elements of exhibitionism, addiction, and obsession when the collection possesses the collector.

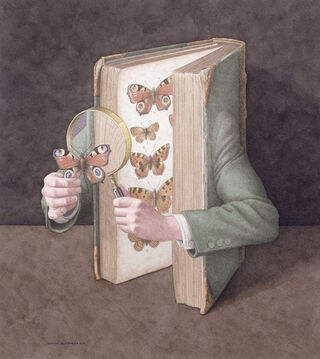

"Let me look at my demon objectively. With the exception of my parents, no one really understood my obsession, and it was many years before I met a fellow sufferer," wrote the internationally renowned novelist Vladimir Nabokov in his autobiography Speak, Memory (1999). Continues Nabokov, "Few things indeed have I known in the way of emotion or appetite, ambition or achievement, that could surpass in richness and strength the excitement of entomological exploration."

Nabokov's passion for collecting butterflies began when he was seven years old. Some aunt or cousin would ask, "Must you really take that net with you? Can't you enjoy yourself like a normal boy?" It continued throughout his life and created for him a "timelessness" and "ecstasy." He describes a "sense of oneness with sun and stone" as he stood in a landscape among rare butterflies. Says Nabokov, " I have hunted butterflies in various climes and disguises: as a pretty boy in knickerbockers and sailor cap; as a lanky cosmopolitan expatriate in flannel bags and beret; as a fat hatless old man in shorts."

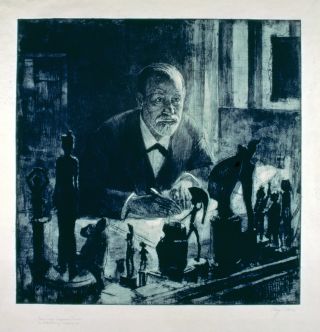

Likewise, Sigmund Freud was another avid collector. For him, books and antiquities from ancient Greece, Rome, and Egypt were his passion, and his office was cluttered with his acquisitions. In an essay on misreading and slips in his book on the psychopathology of everyday life, Freud writes, "Whenever I would walk through the streets of a strange town while on holiday, I read every shop sign that resembles the word in any way as 'Antiquities.' This betrays the questing spirit of the collector" (1901).

Collecting is a “form of play with classification,” i.e., a leisure, voluntary activity “outside the bounds of role obligations" (Danet and Katriel, 2006) though it can "sometimes overshadow" a person's profession or business (Baekeland, 2006).

Collecting does not have to involve concrete objects. For example, birdwatchers can collect sightings of birds, Don Juans can collect sexual conquests, and some can collect ideas, experiences, accolades, or even awards. (Danet & Katriel; Belk et al., 1988).

Collecting implies an order or system, and a collection becomes greater than the sum of its parts. Further, collecting involves a “prolonged activity extending through time” (Pearce, 2006). Many collectors, such as Nabokov, began their interest in collecting as children, usually before puberty (Baekeland).

Collections can “creep up on people unawares" until the moment they realize they have indeed created a collection, with implications of “intentional selection, acquisition, and disposal” (Pearce). “A collection is not a collection until someone thinks of it in those terms” (Pearce).

Sometimes, there is a fine line between collecting and accumulating, depending on the motive, which may change over time (Pearce). The accumulator “passively and uncritically amasses a motley assortment” without symbolic significance. At the same time, the collector “actively seeks out only certain kinds of objects of interest” that tend to have symbolic value and is more discerning in his or her acquisitions (Baekeland).

Further, the accumulator "often maintains a rationalization" about his possessions, "One day these things will come in handy," as "he emphasizes the future, minimizes the present, and ignores the past" (Phillips, 1962). There can be certain shame and displeasure in the accumulation, with attempts to hide it in attics, closets, etc. (Phillips).

The other type of non-collector is the hoarder, a pathological psychiatric condition (Belk et al.; Dozier & DeShong, 2022) and a subject for another discussion.

There can be considerable ambivalence in collecting, and some collectors have spoken of it as a ‘disease’ or a ‘madness’ (Danet and Katriel). Nabokov refers to it as "my demon," himself as a "sufferer," and his passion as an "obsession." "A collection is "an obsession organized" and a collector's interest is not bounded by the intrinsic worth of the objects; whatever they cost, he or she must have them. But If collectors develop "any introspection," they begin at some point to sense that their collection "possesses" them (Aristides, 1988).

Other researchers have acknowledged there can be an addictive quality and a compulsion to collect (Baekeland). Collectors speak of "falling in love" with an object and being unable to resist purchasing it (Danet and Katriel). "It is the nature of desire not to be satisfied" (Aristotle).

There can be an aggressive quality to collecting when it metaphorically resembles a hunt in pursuit of an object of desire (Aristides): "locating the prey, planning for the attack, and acquiring the prey," which then becomes a kind of "trophy" (Formanek, 2006). Philosopher Walter Benjamin wrote, "Collectors are people with a tactical instinct" (1931).

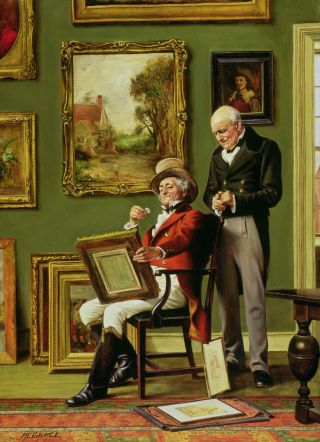

There are many motivations for collecting, including restoring or preserving history, entering a community of like-minded people, or making a financial investment (Formanek). That a collection is recognized by others as worthwhile "legitimizes what is otherwise seen as abnormal acquisitiveness" (Belk et al.).

Collectors' identity and identification with a collection are "complex," and collecting may include aspects of exhibitionism in their wishes to have others see and appreciate the collection. When they share it publicly, they rarely do so anonymously (Baekeland). Further, though many collectors may have considerable difficulty parting with their collection permanently, they may take some solace in obtaining certain immortality by donating their special collections to museums (Belk et al.; Baekeland).

Writes Nobel Prize winner Orhan Pamuk, "...whenever anyone asked what I was going to do with the stuff I was accumulating, I was unable to answer them. 'I will build a museum...'''(2012).

References

Aristides N. Calm and uncollected. American Scholar 57(3): 327-336, 1988.

Aristotle, Politics Book II, Chapter 7, translated by Benjamin Jowett. In: The Basic Works of Aristotle, Edited by Richard McKeon. New York: The Modern Library, 2001, p. 1160.

Baekeland F. Psychological aspects of art collecting. In: Interpreting Objects and Collections, Edited by Susan M. Pearce. New York: Routledge, 2006, pp. 205-219.

Belk RW et al. Collectors and collecting. Advances in Consumer Research 15: 548-553, 1988.

Benjamin W. Unpacking my Library (1931). Translated by Harry Zohn: https://read.amazon.com/?asin=B0BL8VBQX5&ref_=dbs_t_r_kcr (retrieved 12/16/22).

Danet B; Katriel T. No two alike: play and aesthetics in collecting. In: Interpreting Objects and Collections, Edited by Susan M. Pearce. New York: Routledge, 2006, pp. 220-239.

Dozier ME; DeShong HL. The association between personality traits and hoarding behaviors. Current Opinion-Psychiatry 35(1): 53-58, 2022.

Freud S. “Psychopathology of Everyday Life,” Chapter VI: “Misreadings and Slips of the Pen.” In: The Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, The Standard Edition, Volume VI. Edited by James Strachey (1901), p. 110.

Formanek R. Why they collect: collectors reveal their motivation. In: Interpreting Objects and Collections, edited by Susan M. Pearce. New York: Routledge, 2006, pp. 327-335.

Nabokov V. Speak, Memory: An Autobiography Revisted. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Everyman’s Library, 1999.

Pamuk O. The Innocence of Objects. New York: Abrams. Translated from the Turkish by Ekin Oklap, 2012.

Pearce SM. The urge to collect. In: Interpreting Objects and Collections, Edited by Susan M. Pearce. New York: Routledge, 2006, pp. 157-159.

Phillips RH. The Accumulator. Archives of General Psychiatry 6: 474-7, 1962.