Fear

Where Have All the Warriors Gone? Part 2

The necessity of military masculine ideals.

Posted March 28, 2018

Humanity has been at peace for just 8 percent of recorded history. While the origins, causes, and meaning are debatable within their own fields of study, war appears to be an indelible human endeavor.

While the hope and purpose of a democratic society is to only send its military to battle when all other non-violent options have been exhausted, our nation has been at war 222 out of 239 years (this statistic includes U.S. participation in the Banana Wars for nearly 37 years, so interpret with some caution). Regardless of political affiliation, when our elected government chooses to send our military to war, our military goes with the intent of tactical, operational, and strategic victory.

In the first part of this series, it was put forth that the development of multiple masculinities within Western society is potentially problematic for service members transitioning from active duty to the civilian sector. From the condemnation of masculine ideals as toxic to the civilian-military gap, masculinity has not necessarily been afforded the opportunity to argue or establish its relevance in a post-modern society.

It is important to note that masculine traits do not always confer sex, meaning females can possess high levels of masculine traits. This is an important consideration, as 15 percent of active-duty military personnel are women. Many of the experiences of female veterans from the post-9/11 era differ from those of men: They are less likely to have served in combat (30 percent versus 57 percent of men), more likely to have never been deployed away from their permanent duty station (30 percent versus 12 percent of men), and less likely to have served with someone who was killed while performing their duties in the military (35 percent versus 50 percent of men). However, they are EQUALLY as likely to say that their adjustment to civilian life after military service was very or somewhat difficult (43 percent of women, 45 percent of men).

While masculinity is not a universal construct, the dominant Western view includes characteristics such as stoicism, strength, self-reliance, independence, power, and invulnerability. As with anything, taken to the extreme, none of these qualities mete themselves out productively or effectively (stay tuned for Part 3). However, such traits are beneficial, arguably essential, to the waging and winning of war. To negate them in a society that has spent much of its existence engaged in some type of armed conflict is both narrow-minded and foolhardy.

War, the actual engagement of armed participants, is chaos personified. The fog of war, confusion caused by the mayhem of battle, is a very real thing. In such conditions, achieving a sense of internal stability or security in the face of threatening situations can help mitigate against distress. The ability to do so or belief that you are tough, capable, and resilient in the face of challenges and difficulties is the hallmark of self-reliance, an established masculine norm. From the disruptive actions of squad and team-sized elements of paratroopers during WWII to the empowerment of small units during recent military engagements, self-reliance is a seemingly indispensable component of the military person. While war is arguably a team sport, the functionality of the whole is reliant upon the composition of the individual.

To the point, a study with Air Force basic trainees found that self-reliant trainees fared better in training than did their less self-reliant counterparts. In general, they were healthier, possessed higher levels of self-esteem, and exhibited higher completion rates and lower burnout. Whether through self-selection into our all-volunteer force or the weeding out of those not in possession, it stands to reason that the military is largely comprised of men and women who view themselves as self-reliant and engage in associated behaviors.

Stoicism is another factor of the stereotypical masculine gender role, and the modern-day “warrior mindset” neatly aligns with many of its tenets. In both definition and meaning, stoicism has remained nearly unchanged for thousands of years. The classic Greek Stoic philosophy advocates calm in the face of hardship and the ability to modulate the evaluation of events as good or bad. Suppression and emotion control are fundamental components of the modern construct. Expressive suppression, an emotion regulation strategy, is the attempt to hide, inhibit, or reduce ongoing emotionally expressive behavior. This translates positively to the warfighter, as fear is ubiquitous in combat. However, the expression of fear is massively problematic. With evidence to suggest that fear can be spontaneously transmitted, fear contagion in a unit has the potential to consequently impact decision-making and inhibit necessary action.

Moreover, a values-based study of soldiers post-deployment found that hedonism and power, both commonly associated with masculinity, were negatively correlated with the probability and severity of PTSD. Meaning, those who valued one's ability to alter another person's condition or state of mind (power) and possessed the belief that all voluntary human action is rooted in the desire to experience pleasure and avoid pain were less likely to develop PTSD. While the examination of values, gender norms, and psychopathology, especially PTSD, is in its infancy, another quantitative study found that low conformity to masculine norms was associated with suicides in a military population.

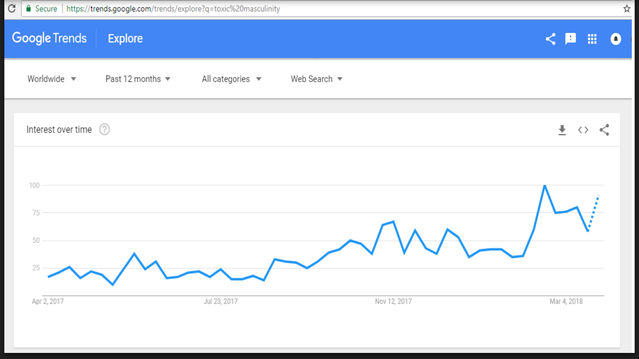

With a rising trend in searches for (see below) and articles/pieces related to "toxic masculinity" (there have been 8 within the past week), we are collectively choosing to ignore the importance of masculinity and its necessary role in the function of society. The choice to downplay or denigrate traditional masculine norms is a choice to field a less lethal, less effective fighting force with a higher likelihood of failing. Unless we bring back the draft and distribute the burden of military or national service onto every American as an obligation of citizenship, warfare remains the obligation of very few with the implicit agreement that their well-being and successful reintegration into civil society is the responsibility of all.