Trauma

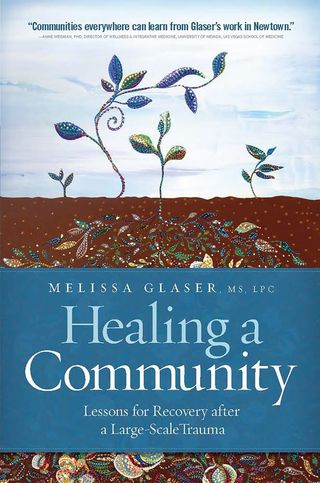

Healing a Community

The Book Brigade talks to community response and recovery leader Melissa Glaser.

Posted January 3, 2019

School shootings. Mass murders. Fires. Floods. The ways that disaster can strike are many. To the physical devastation must be added the emotional impact of events that affect many people and disrupt the soul of the community itself. Heroic as first responders typically are, there are losses that must be attended to over time in order for communities to return to functioning well.

Let’s start with the title, "Healing a Community: Lessons for Recovery after a Large-Scale Trauma." What kinds of events demand concentrated effort of recovery?

The title of the book is meant to capture an understanding of what is entailed when you are in a position to assist or direct community healing following a traumatic event that impacts many individuals as well as the fabric of the community. I share our community recovery model with the hope that others may be able to re-create the work in their own community, regardless of the varying dynamics.

Are you talking about national events that are best addressed through community efforts, or are you talking about events that target a specific community?

This book speaks to events that target specific communities. But again, there are lessons, strategies, and awareness that can be applicable to clinical practice when addressing the impact and outcomes of any tragic event that involves trauma and grief and a need for recovery efforts.

Exactly what kinds events are most disturbing to communities, besides the obvious, and all too common, event of a mass shooting?

I think events that involve loss of life taken in an aggressive and sudden manner are most challenging to heal and recover from. This is not to say that events such as loss due to natural disasters are not very challenging and devastating. However, loss that feels senseless and leaves those that have survived with feelings of fear, helplessness, and unresolved pain is extremely difficult to learn to live with. The trauma from these types of events changes the brain’s response to ongoing life events. An individual’s sense of safety and trust in what should be safe is forever changed.

What happens to communities in the wake of such events?

When a community experiences such an event, the ripples of pain and devastation are far-reaching. The victims are obviously the impacted families that have lost a loved one. But there are so many others whom we tend not to realize are also deeply affected—the first responders, teachers, clergy, municipal staff, babysitters, grandparents, coaches, neighbors, bus drivers, funeral directors, friends, camp counselors, gravediggers, and more. This book is about how to address all of the groups individually and collectively in the healing process.

What is the first thing a community needs?

The initial steps in community recovery work are to define your community and to assess the needs for resources and services and the gaps in services and resources. There are specific ways to conduct such an assessment and empower a community to participate in communicating its needs. Next steps are building a team and infrastructure with a trauma-informed lens.

What is your information based on? Are there studies? Some assemblage of best practices?

My information is based on the research and leaders in the field of trauma to whom my colleagues and I reached out as well as on our own first-hand experience working in the Sandy Hook community. We were informed by authors and approaches that addressed mind-body work as well as by trauma and grief theory and by leaders in community recovery and resilience.

Are there some kinds of people or types of communities that suffer more than others?

I don’t think this work can be put in a quantitative category. Each community that has endured a tragedy that impacts the masses has its own challenges and strengths.

Are there some important things not to do in the aftermath of some group trauma?

Yes. It is important to not step into a community making promises you cannot keep, professing to be the expert that has all the answers, and believing that you will not have a need to spend time assessing and listening and learning as you develop your responses. Programming should always incorporate mind-body strategies to have lasting effects on healing. Programs should never be one and done. You want the work to live on well after your tenure.

What characterizes resilience at the community level?

Resilience is the ability to move from recovery to being able to derive some meaning from the tragic experience. Resilience is when you can embody a sense of self-care and wellness and are able to pass on your knowledge of recovery, kindness, insight, and awareness to others. It’s a type of post-traumatic growth.

What have you found most surprising about recovery efforts you have led?

Most surprising at the time of my work in Sandy Hook was the politics involved in the community recovery, the impact of the money that was needed and that also caused some distress, and the amount of effort it took to engage each affected group in a format accessible to them. My efforts were not always met with open arms. Complicated grief is messy.

What would you identify as the single most important thing to do?

All of your team’s work should be trauma-specific, accessible, and well-informed. There is not one single most important aspect of this work. But the book highlights the importance of assessing and engaging. Partner with your community. Embrace the efforts of those who were there before you and will be there after you. Take care of yourself while immersed in the work. Do not assume that your work will be embraced by all.

Is there a timeline or sequence of stages of recovery against which communities can monitor or benchmark their progress in healing, or does every event have its own trajectory?

I entered the recovery work at Sandy Hook in what we termed the consequence phase. It was a full 18 months after the school shooting. We looked at the initial 18 months as the crisis phase. I think this would be similar in any community experiencing a massive tragedy. The consequences can last for several years. Six years following the event, there are still needs. There are still triggering events that cause pain and suffering to surface.

About THE AUTHOR SPEAKS: Selected authors, in their own words, reveal the story behind the story. Authors are featured thanks to promotional placement by their publishing houses.

To purchase this book, visit: