Child Development

Is Sugar-Coating Bad Childhood Memories a Winning Strategy?

Positive perceptions of early life experience influence outcomes later in life.

Posted November 16, 2018

Do you have “purposely forgotten” or sugar-coated childhood memories about mom or dad that you’ve glossed over using selective amnesia? Do you think retrieval-specific “adaptive forgetting” of negative memories from your childhood and adolescence has made you happier and healthier as an adult? According to a new study published in Nature Communications, the mammalian brain is hardwired to actively forget specific memories that interfere with behavioral goals.

Recently, I asked my 50-year-old sister, Sandy, the two questions mentioned above after reading another new study which found that middle-aged and older adults who had fond childhood memories of their parents as loving and nurturing caregivers from ages 6 to 18 were happier and healthier than adults with lots of bad childhood memories. This paper, “Retrospective Memories of Parental Care and Health from Mid- to Late Life,” was published November 5 in Health Psychology.

The research method of this study relied on two surveys that involved over 22,000 participants. Collectively, these surveys followed people ranging in age from their mid-40s to adults 50 and over. For this particular study, the researchers focused on how memories of caregiver support before the age 18 were retrospectively assessed in midlife and older adulthood. Then, the researchers combed through the data for a possible correlation between self-reported positive vs. negative memories of parental care and self-reported psychological and physical well-being as marked by chronic health conditions or depressive symptoms in mid- to late life.

The researchers found a correlation between people who self-reported having fond memories of caregiving experiences between the age of 6 to 18 with better overall health and fewer depressive symptoms as older adults.

The lead author of this research, William Chopik, is an assistant professor and director of the Close Relationships Lab at Michigan State University in East Lansing. “We know that memory plays a huge part in how we make sense of the world—how we organize our past experiences and how we judge how we should act in the future. As a result, there are a lot of different ways that our memories of the past can guide us," Chopik said in a statement. "We found that good memories seem to have a positive effect on health and well-being, possibly through the ways that they reduce stress or help us maintain healthy choices in life."

Of course, the million-dollar question is: Did all of the respondents who self-reported fond childhood memories actually have higher parental affection and more caregiver support between age 6 to 18? Or have they chosen to use an optimistic, “glass half-full” explanatory style by sugar-coating or purposely forgetting some recollections in a way that facilitates fonder childhood memories?

Along this line of questioning, another study by Chopik from 2015, “Changes in Optimism Are Associated With Changes in Health Over Time Among Older Adults,” found that increases in optimism were associated with improvements in self-rated health and fewer chronic illnesses for adults ranging from 50–70 years of age. Again, these findings raise the question of whether being more optimistic and less pessimistic about the deck you’ve been handed in life is an explanatory style that promotes psychological and physical well-being.

Pragmatic Optimism Can Facilitate Re-Framing Adverse Childhood Experiences as "Opportunities for Growth"

To the best of my knowledge, there is no evidence-based “proof” that sugar-coating bad childhood memories may actually be good for someone’s mental and physical health in the long run. That said, the recent research on happy childhood memories being linked to well-being caused me to do some self-reflection on my own “retrospective memories of parental care” between the ages of 6 to 18. The findings of this study also led to an eye-opening, heart-to-heart conversation with my younger sister about “the good, the bad, and the ugly,” we experienced as adolescents during our parents' “War of the Roses” style divorce.

Our parents took “D-I-V-O-R-C-E being pure H-E double L” to a new level. When my sisters and I were in our mid-teens, our father flipped his lid and moved to Australia to avoid paying child support or alimony. It sucked for all parties involved. That said, he came back to the United States eventually and I was able to forgive him by my mid-20s. Ironically, it wasn’t years of psychoanalysis at the William Allanson White Institute on the Upper West Side that helped me understand why my father abandoned us; it was the line from a pop song, “Oh Father,” by Madonna. She sings, “Maybe someday—when I look back—I'll be able to say: 'You didn't mean to be cruel. Somebody hurt you, too.'”

Both my sister and I use a form of selective amnesia to “purposely forget” most of the bad stuff from our childhood. We also tend to use a sense of humor to “rose-tint” our adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) in a way that makes us laugh. But there’s a caveat: Anyone who has any type of PTSD from psychological, physical, or sexual childhood abuse or experienced the death of a mother or father at a young age knows these types of childhood adversity are never a laughing matter or something to be taken lightly. When my sister and I opened up our collective “memory box” of parental care, some dark childhood memories came to the surface; we shared some gut-wrenching stories that still trigger very sad emotional responses for both of us.

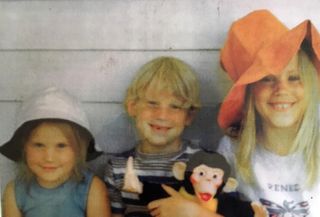

Nevertheless, as anecdotal “Exhibit A & B” my sister and I both have fond childhood memories, and we’re both healthy and happy at 50+ years old. In terms of our perceptions of early life experience, my sister and I both seem to use a form of “pragmatic optimism” in which we aren’t delusional Pollyanna’s who pretend everything was perfect between ages of 6 to 18 but we both tend to focus on the bright side and positive outcomes of the "deck" we were handed. For example, we both look at the abandonment by our father during adolescence as an “opportunity for growth” and "diversifying experience" that gave us mental toughness (MT) and taught us how to cope with life adversity as a doable "Challenge" and not an overwhelming threat.

Despite multiple adverse childhood experiences, we both became self-reliant as teenagers, remain fiercely independent, and have "Openness" to new experiences (OE) as older adults. As an example, my younger sister is a "captain" pilot for FedEx and flies Boeing 777 jumbo jets around the world for a living. She credits healthy doses of childhood adversity with giving her the chutzpah and goal-directed ambition to succeed as a woman in a male-dominated profession.

If you’re heading home for Thanksgiving and have some private time to share childhood memories with your siblings in a way that won’t “stir the pot" of delicate family dynamics or hurt anyone’s feelings... I strongly recommend reminiscing about your childhood memories of parental care. Although I haven’t spoken to my older sister about how she remembers our parents' "caregiving" between the age of 6 to 18, I look forward to having that conversation with her some time when we're alone together over the Thanksgiving holiday.

Lastly, if you have time to share any personal stories and 'retrospective memories of parental care' along with how you think these happy or unhappy recollections may affect your health and happiness in adulthood—please use the comment section below.

References

William J. Chopik and Robin S. Edelstein. "Retrospective Memories of Parental Care and Health from Mid- to Late Life." Health Psychology (First published: November 5, 2018) DOI: 10.1037/hea0000694

Pedro Bekinschtein, Noelia V. Weisstaub, Francisco Gallo, Maria Renner, Michael C. Anderson. "A Retrieval-Specific Mechanism of Adaptive Forgetting in the Mammalian Brain." Nature Communications (First published: November 7, 2018) DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-07128-7

William J. Chopik, Eric S. Kim, Jacqui Smith. "Changes in Optimism Are Associated With Changes in Health Over Time Among Older Adults." Social Psychological and Personality Science (First published: June 29, 2015) DOI: 10.1177/1948550615590199

Melissa T. Merrick, Derek C. Ford, Katie A. Ports, Angie S. Guinn. "Prevalence of Adverse Childhood Experiences From the 2011-2014 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System in 23 States." JAMA Pediatrics (First published online: September 17, 2018) DOI: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2537

Simone M. Ritter, Rodica Ioana Damian, Dean Keith Simonton, Rick B. van Baaren, Madelijn Strick, Jeroen Derks, Ap Dijksterhuisa. "Diversifying Experiences Enhance Cognitive Flexibility." Journal of Experimental Social Psychology (First published online: February 12, 2012) DOI: 10.1016/j.jesp.2012.02.009