Depression

Neuroscience Pinpoints Unique Way Exercise Fights Depression

Vigorous exercise increases neurotransmitters that can minimize depression.

Posted February 28, 2016

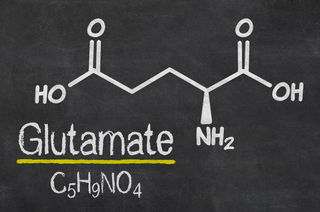

Neuroscientists at the University of California at Davis (UC Davis) have pinpointed how exercise improves mental fitness and reduces depressive symptoms. The researchers found that vigorous bouts of exercise increase levels of two common neurotransmitters—glutamate and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)—which are responsible for chemical messaging between neurons within the human brain.

GABA is the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter of our central nervous system. Its principal role is to reduce the excitability of neurons throughout the nervous system. In humans, GABA is also responsible for the regulation of muscle tone. In neuroscience, glutamate is an important excitatory neurotransmitter that plays a principal role in neural activation. The UC Davis researchers found that GABA and glutamate levels increased in the participants who exercised vigorously, but not among the non-exercisers.

The February 2016 study, “Acute Modulation of Cortical Glutamate and GABA Content by Physical Activity,” was published in the Journal of Neuroscience. This study advances our understanding of the underlying molecular brain mechanisms of physical activity. It also fine-tunes our understanding of why aerobic exercise has a wide range of benefits regarding depression, neuropsychiatric disorders, neurorehabilitation, aging, and cognitive function.

Exercise Optimizes Brain Structure and Functional Connectivity

In The Athlete’s Way: Sweat and the Biology of Bliss, I discuss the ability of exercise to increase GABA production in ways that minimize stress and anxiety. In chapter three, “The Brain Science of Sport,” I divide the exploration of the brain into three basic categories: architectural (physical structure), chemical (molecules/neurotransmitters), and electrical function (neuron firing rates).

From an electrical standpoint, a variety of human studies have shown that physical activity leads to a generalized increase in electroencephalography (EEG) brain power across multiple brain regions on various frequencies. Structurally, aerobic exercise is known to increase gray matter brain volumes and optimize white matter connectivity. On p. 103 of The Athlete's Way, in a section on neurochemicals, I wrote,

“The neurochemicals released during exercise are so potent that you could consider yourself a psychopharmacologist, self-medicating through exercise. There is a strong correlation between the quantity of certain neurotransmitters in your brain and your mood. Exercise has been shown across the board to improve the chemical environment of your brain in the long and short term. For people who are not clinically depressed, recent studies have shown exercise to be one of the most reliable long-term mood boosters on the planet.

Research on the chemical processes and long-term effects of consistent exercise on mental health, learning, and memory is still being conducted. The study of these antidepressant chemicals helps to reveal the chemical properties of depression and mood. The psychopharmacological power of exercise should not be underestimated, but it is not a panacea for all mental illness.”

In the latest study from UC Davis, the researchers conducted a state-of-the-art series of proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies in human volunteers before and after exercising vigorously between 80 to 85 percent of maximum heart rate peddling on a stationary bicycle to measure levels of GABA and glutamate.

Vigorous Exercise Increases Production of GABA and Glutamate

Neurotransmitters drive communications between various brain cells that regulate our psychological and emotional well-being. This experiment measured glutamate and GABA in two different parts of the brain immediately before and after three vigorous exercise sessions that lasted between eight and 20 minutes. Similar measurements were also made for a control group that didn’t exercise.

In particular, significant increases of both GABA and glutamate were found in the visual cortex, which processes visual information. These results confirm the exercise-induced expansion of the cortical pools of glutamate and GABA, and expand our understanding of the distinctive brain states triggered by physical activity and cardiorespiratory fitness.

The study also identified an increase in glutamate following exercise in the anterior cingulate cortex, which helps regulate heart rate, as well as performs other functions related to cognition and emotional processing. Although the brain benefits of intense exercise dissipated when someone stopped working out, there was some evidence of longer-lasting effects. These findings corroborate the prescriptive advice and evidence presented in The Athlete’s Way.

The new insights on brain metabolism and exercise illuminate why aerobic exercise helps millions of people around the globe combat depression. The researchers believe these findings validate that vigorous exercise may be an effective therapy for many people suffering from depression. They claim that exercise could be especially useful for patients under age 25, who are often more susceptible to the side effects of antidepressants such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

In a press release, lead author Richard Maddock, UC Davis professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, said,

"Major depressive disorder is often characterized by depleted glutamate and GABA, which return to normal when mental health is restored. Our study shows that exercise activates the metabolic pathway that replenishes these neurotransmitters. From a metabolic standpoint, vigorous exercise is the most demanding activity the brain encounters, much more intense than calculus or chess, but nobody knows what happens with all that energy. Apparently, one of the things it's doing is making more neurotransmitters."

The new findings by Maddock and his colleagues are an important step towards understanding the complexities of brain metabolism. This research also hints at the negative impact that sedentary lifestyles might have on brain function and neurotransmitter production.

There may also be a link between "bonking" and glutamate levels during endurance athletics. "It is not clear what causes people to 'hit the wall' or get suddenly fatigued when exercising," Maddock said. "We often think of this point in terms of muscles being depleted of oxygen and energy molecules. But part of it may be that the brain has reached its limit. There was a correlation between the resting levels of glutamate in the brain and how much people exercised during the preceding week."

How Do You Calculate 80% of Your Maximum Heart Rate?

Technically, getting an accurate calculation of your maximum heart rate (MHR) outside of an exercise physiology laboratory is difficult. That said, you can use some simple formulas and rated perceived exertion (RPE) to identify a general ballpark that corresponds to your various cardiovascular heart rate zones.

In broad sweeping terms, the simplest formula for calculating MHR is 220 minus your age. You can wear a heart rate monitor or use a fitness watch to monitor your heart rate and make mathematical calculations. You can also use a talk test combined with a simple color coded rating system from yellow-to-red based on perceived exertion.

The 5-Point Rating Perceived Exertion Scale and Talk Test by Bergland

1. VERY EASY: You could sing a song (40 to 50 percent of maximum heart rate. Light yellow color rating). This would correlate to a casual walking pace.

2. EASY: You could carry on a conversation (50 to 60 percent. Bright yellow color rating). This is equivalent to a brisk walking pace.

3. MODERATE: You could speak four- to six-word sentences (60 to 80 percent. Orange color rating) This is a "tonic level" of aerobic exercise (such as jogging) that causes you to break a sweat without being extremely taxing.

4. HARD: You could express short two- or three-word thoughts (80 to 85 percent. Reddish-orange color rating) This is the level recently shown to increase production of GABA and glutamate with a cumulative time of 8 to 20 minutes.

5. VERY HARD: You could grunt and use sign language (85 to 100 percent. Red color rating) This level of exertion is classically known as "red-lining" and is sustainable for very short time periods such as during a sprint.

For more free advice on putting together a well-balanced cardio regimen, click here to read "The Cardio Program" chapter of The Athlete's Way.

Conclusion: Interval Training Facilitates Bursts of Intense Exercise

As a coach, I always recommend mixing up your levels of aerobic intensity. To optimize the full spectrum of brain benefits, the latest research suggests that short bursts of intense exercise can trigger the production of GABA and glutamate. When deciding to increase the intensity of your exercise, always use common sense and consult with your doctor first.

Interval training at a rate of 80 to 85 percent of your maximum heart rate followed by a period of recovery is a sustainable way to exercise vigorously while increasing your cardiorespiratory fitness. For example, if you normally ride a stationary bike at level 8 for 30 minutes, you could break the workout into five 6-minute blocks in which you bike at level 10 for 3 minutes, and recover at level 6 for 3 minutes. Repeat this 5 times.

Based on the latest findings, this type of workout will kickstart your GABA and glutamate production and improve both your physical and mental fitness without shocking your body. Also, at the end of a 30-minute workout, you would have spent 15 minutes biking at a more intense pace than usual. This increases your VO2 and will eventually allow you to work out harder with less perceived exertion.

In future studies, Maddock and his team are going to investigate whether a less-intense aerobic activity, such as walking, offers similar brain benefits to vigorous exercise. They would also like to use their high tech “exercise-plus-imaging method” to identify exactly what types of exercise offer the greatest benefits for combating depression.

"We are offering another view on why regular physical activity may be important to prevent or treat depression," Maddock concluded. "Not every depressed person who exercises will improve, but many will. It's possible that we can help identify the patients who would most benefit from an exercise prescription."

Stay tuned for future breakthroughs in this exciting field of research. To read more on this topic, check out my previous Psychology Today blog posts,

- "The Neurochemicals of Happiness"

- "Combining Aerobic Exercise and Meditation Reduces Depression"

- "Why Does Physical Activity Improve Cognitive Flexibility?"

- "Alpha Brain Waves Boost Creativity and Reduce Depression"

- "Can Exercise Protect Your Brain From Depression?"

- "More Proof That Aerobic Exercise Can Make Your Brain Bigger"

- "Physical Activity Is the No. 1 Way to Keep Your Brain Young"

© 2016 Christopher Bergland. All rights reserved.

Follow me on Twitter @ckbergland for updates on The Athlete’s Way blog posts.

The Athlete’s Way ® is a registered trademark of Christopher Bergland.