Flow

"Superfluidity" and the "Hot Hand" Are Synonymous

Superfluidity and the "hot hand" exist in both sports and the creative process.

Posted November 10, 2015

Recently, David Remnick wrote a brilliant article in the New Yorker, Bob Dylan and the “Hot Hand", which reminded me of concepts I’ve been trying to convey about the extraordinary—but also universal—experience of “superfluidity.” After reading Remnick's essay, it's clear to me that "the hot hand" and "superfluidity" occur both in sports and the creative process.

The Austrian philosopher, Ludwig Wittgenstein, once said, " A new word is like a fresh seed sewn on the ground of discussion." I agree. "Superfluidity" is one of these words. For over a decade, I’ve been discussing my concept of superfluidity which is a word I borrowed from physics and coined to describe the ecstatic second-tier of flow.

In The Athlete's Way, I describe my discovery of the concept of superfluidity on pp. xiv-xv, in A Note from the Author,

"As an athlete I could break free of the daily grind if I worked hard physically and used my imagination ... It was a metaphysical experience for me as a teenager, because I realized that I and "the other" were one. This experience of complete connectedness is what I have coined superfluidity—the episodic feeling of existing without any friction or viscosity—a state of pure bliss I will explore in this book."

This BBC clip shows superfluidity in a physics laboratory:

In many ways, "superfluidity" and the “hot hand” are synonymous. Just like being "in the zone” and “flow” are two different terms used to describe a singular experience, superfluidity and the hot hand are the same thing.

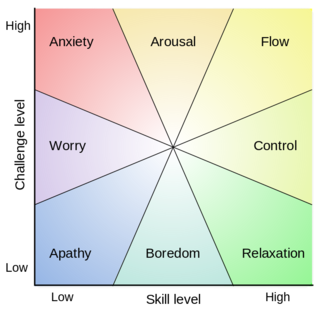

Flow is described as a joyful state that occurs when a person is totally focused and immersed in an activity and the challenge perfectly matches his or her level of skill. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi first defined flow in his seminal book Beyond Boredom and Anxiety: Experiencing Flow in Work and Play (1975). He later acknowledged that, “there seems to be a need to reinvent or re-express the answer of what to do to create flow every couple of generations.”

What Is Superfluidity?

Superfluidity is the ultimate flow experience. It is an ego-less state of performance marked by zero entropy, friction or viscosity, as well as, superconductivity. Superfluidity is a state of perfect synchronicity, harmony, and infinite energy. Creating flow can become a daily experience once you learn how to stay in the “flow channel” by constantly matching your level of skill with your level of challenge. Superfluidity is much more mysterious and less predictable than flow. Unfortunately, it's also episodic, elusive, and short-lived, too.

The sweet spot of flow lies between the anxiety caused by a challenge being too difficult, and the boredom caused by a challenge being too easy.

Csikszentmihalyi describes an "ecstatic state" or a feeling that artists, athletes, and musicians have of being outside of what they were creating with their hands or body when describing flow. I believe that when this happens, it's important to differentiate that the "out of body" aspect of flow is actually superfluidity. Being in a state of flow feels good, but it is not always "ecstatic."

Ecstasy in Greek means “to stand outside oneself.” You can't be in a constant state of ecstasy when you're creating flow. Mastery takes time, patience and... practice, practice, practice. You need to be firmly grounded in your body to lay down the muscle memory in your cerebellum which holds the key to the mastery that enables superfluidity. Only through this type of practice and repetition can someone create the launching pad for the "hot hand" of superfluidity in sports or the arts.

When Roger Bannister described breaking the four-minute mile, he said, ”No longer conscious of my movement, I discovered a new unity with nature. I had found a new source of power and beauty, a source I never dreamt existed.” He is describing superfluidity, not regular flow. Likewise, when artist Paul Klee says, “Everything vanishes around me, and works are born as if out of the void. Ripe, graphic fruits fall off. My hand has become the obedient instrument of a remote will.” This is not just flow, it is superfluidity.

Superfluidity and the “Hot Hand” Are Synonymous

In his New Yorker piece, Remnick writes, “For decades, there’s been a running academic debate about the question of “the hot hand”—the notion, in basketball, say, that a player has a statistically better chance of scoring from downtown if he’s been shooting that night with unusual accuracy." He goes on to say,

"Thirty years ago, Thomas Gilovich, Amos Tversky, and Robert Vallone seemed to squelch the hot-hand theory with a stats-laden paper in the journal Cognitive Psychology, but, just last year, along came Joshua Miller and Adam Sanjurjo, marshalling no less evidence, to insist that an “atypical clustering of successes” in three-point shooting was not a “widespread cognitive illusion” at all, but rather that it “occurs regularly.”

What’s clear is that when it comes to the life of the imagination, the hot hand is a matter of historical fact. Novelists, composers, painters, and poets are apt to experience stretches of intense creativity that might derive from any number of factors—surrounding historical events, artistic rivalries, or, most mysteriously, inspiration—but the streak is undeniably there.”

Remnick connects-the-dots of how creative greats from Shakespeare to the Beatles had intense, prolific creative output or the "hot hand" during short periods of time. For example, he points out that from 1972 to 1976, Stevie Wonder, produced a mind-boggling string of incredible albums: “Music of My Mind,” “Talking Book,” “Innervisions,” “Fulfillingness’ First Finale,” and “Songs in the Key of Life.”

Remnick writes, “For Dylan, the greatest and most abundant songwriter who has ever lived, the most intense period of wild inspiration and creativity ran from the beginning of 1965 to the summer of 1966 ... Dylan was exploding with things to say and sing. As he later acknowledged, it was as if he were taking dictation from somewhere, from somebody. And, at the same time, he seemed on the brink of self-annihilation."

In an interview for 60 Minutes, Ed Bradley asked Bob Dylan, "I read somewhere that you wrote "Blowin' in the Wind" in 10 minutes. Is that Right?" Dylan responded, "Probably... Those early songs were almost magically written. Try to sit down and write something like that. There's a magic to that, and it's not Siegfried and Roy kind of magic, you know? It's a different kind of a penetrating magic. And, you know, I did it. I did it at one time."

Bradley then asks Dylan if he thinks he could do it again today? “No,” says Dylan. "You can't do something forever. I did it once, and I can do other things now. But, I can't do that." Here is the complete interview, if you're interested:

Conclusion: Superfluidity and a Sense of Wonder

The conclusion of Bob Dylan acknowledging that he had tapped into something magical as a songwriter at one point in his life, but that he couldn’t continue to create that way for perpetuity is a valuable lesson about superfluidity. Like the "hot hand," superfluidity is always going to be episodic and short-lived.

For many athletes and creative people who have achieved superfluidity, there can be a tendency to self-destruct when you realize that you don’t have the “hot hand” anymore. There are so many tragic examples of superstars like Michael Jackson, Jimi Hendrix, and Janis Joplin imploding either at their zenith or in the aftermath.

As an athlete, there was a period that I mourned the fact that growing older and past my prime shut me out of ever being able to experience superfluidity or having the "hot hand" again. I will never have athletic moments of superfluidity that would be classified as the “hot hand” by onlookers again in my lifetime ... I'm no longer a supernova capable of the “hot hand” by becoming a conduit for some outside energy source that connects me with "the other" athletically. I've accepted this, and it’s fine with me.

Luckily, in the decade since I retired from athletic competition, I’ve learned how to embrace the transition from “otherworldly” peak experiences of superfluidity to more commonplace moments of awe and a sense of wonder in my daily life that are both transcendent and ecstatic. Almost every day, I have some type of “wow” moment that has nothing to do with creative output or a need-for-achievement.

After reading Remnick's essay, I'm convinced that the secret to gracefully surviving the end of any “hot hand” period of superfluidity is to remember the wisdom of Bob Dylan when he says without remorse, "You can't do something forever. I did it once, and I can do other things now. But, I can't do that."

If you’d like to read more on this topic, check out my Psychology Today blog posts,

- "Peak Experiences, Disillusionment, and the Joy of Simplicity"

- "The Dark Side of Mythic Quests and the Spirit of Adventure"

- "The Power of Awe: A Sense of Wonder Promotes Loving-Kindness"

- "Superfluidity: Decoding the Enigma of Cognitive Flexibility"

- "The Neuroscience of Superfluidity"

- "Superfluidity: Beyond a State of 'Flow'"

- "Supefluidity: The Psychology of Peak Performance"

- "The Neuroscience of Madonna's Enduring Success"

- "The Cerebellum May Be the Seat of Creativity"

© 2015 Christopher Bergland. All rights reserved.

Follow me on Twitter @ckbergland for updates on The Athlete's Way blog posts.

The Athlete’s Way ® is a registered trademark of Christopher Bergland.