Child Development

Childhood Family Problems Can Stunt Brain Development

Family problems during childhood can reduce brain volume of the cerebellum.

Posted February 21, 2014

New research from the UK has found that exposure to common family problems during childhood and early adolescence can stunt healthy brain development, which could lead to mental health issues later in life.

The study led by Dr. Nicholas Walsh, lecturer in developmental psychology at the University of East Anglia (UEA), used brain imaging technology to scan teenagers aged 17-19. The researchers found that those who experienced mild to moderate family difficulties between birth and 11 years of age developed a smaller cerebellum.

The cerebellum (Latin: little brain) is associated with skill learning, proprioception, stress regulation, sensory-motor control and many other functions. Although the cerebellum is only 10% of brain volume, it houses over 50% of the brain’s total neurons.

Dr. Walsh and colleagues believe that a smaller cerebellum may be a risk indicator of psychiatric disease later in life. According to the researchers the cerebellum is consistently found to be smaller in virtually all psychiatric illnesses. Although a smaller cerebellum is linked to psychiatric illnesses the exact reason for this is not completely understood.

The study, titled “General and Specific Effects of Early-Life Psychosocial Adversities on Adolescent Grey Matter Volume” was conducted with the University of Cambridge and the Medical Research Council Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit. The findings were published on February 19, 2014 in the journal NeuroImage: Clinical.

Whatever the Cerebellum Is Doing, It’s Doing a Lot of It

Cerebellum in red.

The exact role of the cerebellum in emotional and cognitive function remains enigmatic to neuroscientists. My father—who was a neuroscientist and neurosurgeon—was fascinated by the mysterious and powerful cerebellum. These new findings add to growing research that shows the importance of the cerebellum in optimizing overall brain function.

My dad always said, “Whatever the cerebellum is doing, it’s doing a lot of it.” My father passed his obsession with the cerebellum on to me. The Athlete's Way is founded on the principle of optimizing the gray and white matter volume and connectivity of both hemispheres of the cerebellum with both hemispheres of the cerebrum through daily lifestyle choices at every stage of life.

Exactly how the two hemispheres of the cerebellum interact with both hemispheres of the cerebrum is not totally understood. That said, it is clear that daily habits and environmental factors can dramatically alter the structure, function, and connectivity of all four brain hemispheres for better or worse.

Common Childhood Family Problems Can Reduce Cerebellum Size

Previous studies have focused on the effects of severe neglect, abuse and maltreatment in childhood on brain development. The goal of Dr. Walsh's research was to determine the impact—in currently healthy teenagers—of exposure to more common but relatively chronic forms of 'family-focused' problems.

Family problems included significant arguments or tension between parents, physical or emotional abuse, lack of affection or communication between family members, and events which had a practical impact on daily family life and might have resulted in health, housing or school problems.

Dr. Walsh said: "These findings are important because exposure to adversities in childhood and adolescence is the biggest risk factor for later psychiatric disease. Also, psychiatric illnesses are a huge public health problem and the biggest cause of disability in the world."

Walsh added, "We show that exposure in childhood and early adolescence to even mild to moderate family difficulties, not just severe forms of abuse, neglect and maltreatment, may affect the developing adolescent brain. We also argue that a smaller cerebellum may be an indicator of mental health issues later on. Reducing exposure to adverse social environments during early life may enhance typical brain development and reduce subsequent mental health risks in adult life."

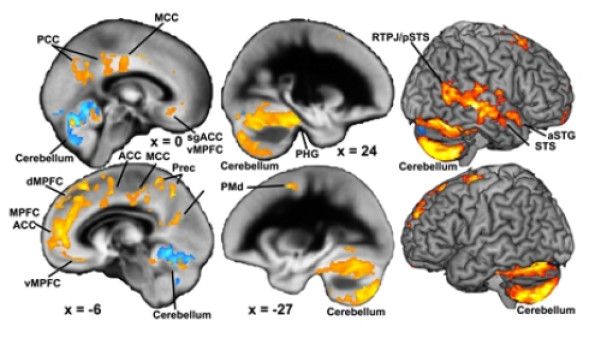

Brain volume changes caused by family problems in orange and blue.

The 58 teenagers who took part in the brain scanning were drawn from a larger study of 1,200 young people, whose parents were asked to recall any negative life events their children had experienced between birth and 11 years of age.

A "significant and unexpected" finding was that the participants who reported stressful experiences when aged 14 were subsequently found to have increased volume in more regions of the brain when they were scanned at ages 17-19.

Dr. Walsh hypothesizes that this could mean that mild stress occurring later in development may 'inoculate' teenagers, enabling them to cope better with exposure to difficulties in later life, and that it is the severity and timing of the experiences that may be important.

Conclusion: Psychosocial Environments Alter Brain Structure and Function

The researchers found that those who had experienced family problems were more likely to have had a diagnosed psychiatric illness, have a parent with a mental health disorder and have negative perceptions of how their family functioned. This study offers new clues on the connection between psychosocial environments and brain structure, but more research is needed.

"This study helps us understand the mechanisms in the brain by which exposure to problems in early-life leads to later psychiatric issues," Dr. Walsh concluded. "It not only advances our understanding of how the general psychosocial environment affects brain development, but also suggests links between specific regions of the brain and individual psychosocial factors. We know that psychiatric risk factors do not occur in isolation but rather cluster together, and using a new technique we show how the general clustering of adversities affects brain development."

If you'd like to read more on this topic, check out my Psychology Today blog posts:

- "How Is the Cerebellum Linked to Autism Spectrum Disorders?"

- "The Neuroscience of Calming a Baby"

- "Chronic Stress Can Damage Brain Structure and Connectivity"

- "Loving Touch Is Key to Healthy Brain Development"

- "Parental Warmth Crucial to a Child's Well-Being"

- "Toward a New Split-Brain Model: Up Brain-Down Brain"

- "One More Reason to Unplug Your Television"

- "No. 1 Reason Practice Makes Perfect"

- "Better Motor Skills Linked to Higher Academic Scores"

- "The Neuroscience of Imagination"

- "Too Much Crystallized Knowledge Lowers Fluid Intelligence"

- "Gesturing Engages All Four Brain Hemispheres"

- "The Neuroscience of Superfluidity"

Follow me on Twitter @ckbergland for updates on The Athlete’s Way blog posts.