Environment

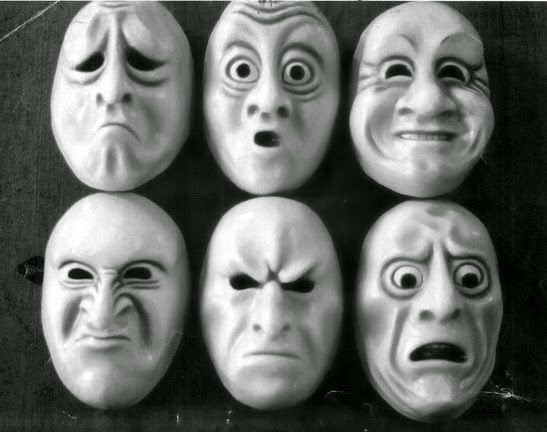

The Faces of Emotions

Are they universal or culturally varied?

Posted September 18, 2019 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Cultural differences should not separate us from each other, but rather cultural diversity brings a collective strength that can benefit all of humanity. —Robert Alan

Facial expressions are a window to one’s soul; they are also a way to learn more about the physical environment without having a first-hand experience of the surroundings. For example, by looking at another person’s face, you can decide to try a new food, receive reassurance to continue with an action, or determine whether there is a threat nearby. Being able to reliably interpret facial expressions would be highly adaptive if it is also a way to anticipate other people’s most likely next action. From these resultsthe need to:

- Produce reliable signals for others to use.

- Be able to read and interpret those signals.

A universality of sorts in facial displays would be helpful in the interpretation of expressions as people around the globe would have the same codes and would thus understand facial cues in similar ways, regardless of the culture or origin of the sender (i.e. the one producing the expression).

Universal facial expressions?

Paul Ekman and his colleagues were the first to look at facial displays in different cultures in the 1970s, looking at spontaneous displays in various contexts, and soon found the core question in this matter: “Are facial expressions universal?” They focused on facial displays of primary emotions because if any expression was universal, it was assumed it would be one representing a biologically-based/physiological response. In order to prove their assumption of universality right, they showed Western faces posing one of the six primary emotions — anger, fear, happiness, disgust, sadness, and surprise — to an isolated tribe from Papua, New Guinea, which had had very little (if any) contact with people from Western societies; they also collected photos of the members of the tribe’s expressions. The idea was that if people from an isolated tribe, with no previous exposure to American facial expressions, could understand which emotion was presented (and vice versa), facial expressions of emotion must be universally expressed.

They asked people in each group (Papua vs the U.S.) to identify which emotion they thought was displayed on faces of individuals from either the same group or a different culture. People in both cultures were able to identify the correct emotion associated with facial expressions. From this, Ekman and his colleagues confirmed their idea that facial expressions of primary emotions were correctly identified/labeled cross-culturally. They defined prototypical displays for each of the six so-called primary, basic emotions; they argued that those displays were innate and universal as people from different cultures could recognize the emotion expressed and displayed it themselves in a very similar way.

Even though this experiment presented some flaws and its methods are now outdated, the study opened the way to cross-cultural studies of facial displays and expressions and led the way to the development of a new theory: cultural accents.

When studying facial expressions of primary emotions, researchers can rely on physiological changes to confirm the emotional state of the subject (i.e., elevated heart-beat, sweat production, pupil dilatation). When investigating secondary emotions, researchers have no choice but to rely on self-report (i.e., asking the person how they think they feel) to assess the emotional state of the subject. We need to rely on people’s knowledge of their emotions and their ability to describe their feelings to associate those states with facial movements observed in a given context. We need the verbal to study the non-verbal.

Secondary emotions, their development and expression, are more likely to be culturally influenced with bigger differences between people. The cultural environment an individual grows into is supposed to influence the context in which emotion should be felt and expressed; the social context provides display rules and teaches when it is socially appropriate to display your feelings. Contrary to primary emotions, it has been said that secondary emotions do not have prototypical, universal facial expressions; following research has identified facial traits reliably associated with some reported secondary emotions such as shame, embarrassment, and contempt. Those facial traits cannot be defined as prototypical displays because they are usually one or two movements associated with various other non-defined movements, susceptible to variation between individuals.

When looking at cultural differences in facial expressions of emotion, there are two main schools of thought:

- The evolutionist view, which holds that, if facial expressions conveyed an important message, then they should be universally displayed and recognized due to natural selection

- The partisans of culture-specific expressions, or cultural accents, defending that emotions and their facial displays are heavily influenced by the sociocultural contexts studied

Does it have to be an either-or debate?

The ability to be better at reading familiar faces (i.e., relatives and people from your cultural group) is defined as the ‘in-group advantage’; gestural and facial communication differ between cultures and even within a culture. For instance, Italians and French natives both use their hands a lot when talking but their gestures differ in both forms and meanings. However, some movements are universally understood and allow basic communication between people speaking different languages. Cultural differences ought not to contradict an evolutionary view of facial expressions as different cultures may rely on different facial cues, functional in a given culture and for a given emotion. Moreover, it is also possible that a situation elicits different emotional responses in different cultures, resulting in different facial displays. Having some degree of standardized, recognizable facial traits makes sense in an evolutionary, adaptationist framework, but universality of form does not exclude variation in use.

Looking around us, being exposed to people from different countries broadens our comprehension of non-verbal communication and allows us to get better at understanding how the face is used in social interactions. Indeed, we should see faces not as the readouts of our internal emotional states, but as a social tool used to influence and manipulate interactions.